1 International Management Institute, New Delhi, Delhi, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

The organisations in the corporate world are bound to face numerous challenges on regular basis. Various generations are working in the organisations at the same time and this generational diversity poses an avoidable challenge for the organisations irrespective of the nature of the industry and location.

Purpose: The author aims to answer the following questions in the article: (a) whether iGen is significantly diverse from the other previous generational cohorts, (b) to determine the themes and contexts in which generational diversity and iGen have been studied, (c) to identify the gaps in the existing literature regarding the study of generational diversity and iGen and (d) to determine the future scope for the researchers to study regarding generational diversity and iGen.

Methodology: Scopus database has been used in this study and 60 articles have been picked out from the database of 791 articles for the review. TCCM framework has been utilised for this study.

iGen, generational diversity, TCCM, Gen Z

Introduction

Organisations in the current era consist of various generational cohorts positioned on a variety of job roles. At present, majority of the job positions are found to be taken by the employees belonging to the two generations, that is, Generation X and Millennials. These two generations have been profoundly studied by many researchers.

Generation X was named by a novelist Doug Coupland (Howe & Strauss, 1992). The individuals whose birth year lies between 1963 and 1981 are considered to be a part of Generation X (Fry, 2018). Generation Y or Millennials comprise the individuals whose birth years lies between 1981 and 1995 (Gabrielova & Buchko, 2021; Akçay, 2022). The upcoming generation, Generation Z or iGen, is the population whose birth year lies between 1995 and 2012 (Pichler et al., 2021).

Gen X and Gen Y have already been studied profoundly (Gabrielova & Buchko, 2021), while the literature is scarce about iGen. Neil Howe and William Strauss (1992) explained in their generational theory that individuals who took their birth in a particular time frame are considered to belong to the same generation. Individuals of a generation are found to have some similarities between themselves. However, their values and characteristics are different from other generations due to their differing experiences and exposures (Verlinden, n.d.). Generational diversity refers to the diversity that originates from the fact that many generations work simultaneously in an organisation. This article aims to study the generational diversity by reviewing the existing literature.

Contextual Background

Generations

A well-known sociologist named Karl Mannheim is credited for proposing the term ‘Generation’. He recommended that generation is a bunch of individuals whose birth year lies in a range and who have shared and encountered similar situations and circumstances (Mannheim, 1993). On the basis of generational theory, researchers have stated that individuals have been grouped and classified as belonging to the same generation, if they have encountered similar experiences and events in the initial years after their birth and during the developmental stages of their lives (Jung et al., 2021; Ryder, 1965). Researchers emphasised that the labels of generation can be viewed as a component of individual’s identity. The term ‘Cohort’ describes the generational group that shares the birth year and has faced identical historic events (Joshi et al., 2010; Smola & Sutton, 2002).

iGen

Individuals who belong to the generational cohort of iGen are found to be born between 1995 and 2010. Occasionally, this generation is labelled by a number of titles, that is, Gen Z, ‘Me’, Generation and Digital Natives (Francis & Hoefel, 2018; Pichler et al., 2021).

Several features of iGen are emphasised in the literature. Such characteristics suggest that iGen is a generation that grew up in an era where technology and the internet were commonplaces and easily available. Their entire lives they have been using technology for a variety of activities, including everyday tasks, communication and enjoyment. They frequently use internet-based educational tools for improving their skills. This encourages the development of individualistic work-related behavioural preferences and it contributes in their inclination towards more individualistic approach over social approach of working. They encounter difficulties when collaborating in groups within the companies (Pichler et al., 2021). This generation places a strong emphasis on accomplishments. iGen seems to be more accepting of diversity and inclusion than previous generations. However, there is an increased possibility that they may experience mental health issues (Pichler et al., 2021; Schroth, 2019). Researchers have found and stated that iGen has the need to feel appreciated and encouraged by organisations (Pichler et al., 2021). According to research, iGen is more likely to use organic items than plastic ones. Since they do not hurt the environment (Dangelico et al., 2010; Jain et al., 2006), their green consumption, behaviour and values are positively impacted by their awareness of issues, concern for the environment and green knowledge (Nguyen et al., 2022). iGen has the need to feel worthy for the organisations to motivate themselves to broaden their knowledge and skill inventory (Pichler et al., 2021).

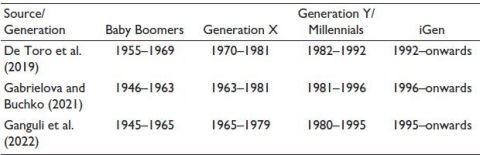

Many researchers have noted that the primary source of puzzlement exists in the birth year when it comes to assigning labels of the generational cohort (Prund, 2021). It is demonstrated in Table 1 how various authors employed varying years while labelling the generations.

Generational Diversity

Generational diversity refers to the diversity based on the birth-year identifiable groups that is termed as generations in the organisations. It is those rare times in the history that the workspaces have a rising mix of independent generational groups working simultaneously in the organisations (Ballone, 2007; Haynes, 2011).

According to generational theory, each generation has distinctive expectations, experiences and history that reflect generations’ lifestyles and attitudes (Strauss & Howe, 1991). Each generation bring their own unique flavour and bunch of characteristics and values into the organisation (Gabrielova & Buchko, 2021).

Table 1. Generation Labels and Birth Year Range Utilised by Distinct Researchers.

At present, one of the crucial challenges faced by the organisations and the workplaces is generational diversity (Prund, 2021). However, diversity in terms of generations is essential for the organisations to face highly competitive, dynamic and ambiguous scenarios in the marketplace and the industry (Amayah & Gedro, 2014).

Age diverseness is said to impact various organisational HR procedures including management of disputes, personnel training, development of the career paths and workforce retention, channels of knowledge sharing and remuneration policies (Williams, 2016). iGen behaves, feels and functions differently from the previous generations (Francis & Hoefel, 2018).

Methodology

This study aimed to explore the concept of generational diversity in the workplace keeping iGen under the lens. In order to study the existing themes and to determine the unexplored areas, it was recommended to conduct a systematic literature review (SLR) and theory, context, characteristics and methodology (TCCM) framework has been selected. It has been highlighted that the change in context brings the change in other aspects of the similar research topic, especially related to human resource (Zehetner et al., 2022) which makes TCCM even more efficient for an SLR study. The database selected for this study was Scopus, since it sizably covers the publications across a variety of disciplines.

Stage 1: Acquisition

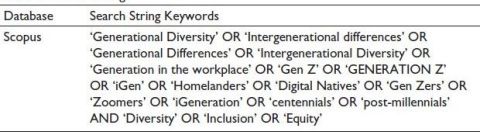

The acquisition process initiated with using the Google Scholar in order to obtain a good keyword combination. ‘Generation Z’ and ‘Generational Diversity’ were typed one after the other to explore the other keywords which are widely used interchangeably for these words. The search string used in the search of documents on the Scopus has been mentioned in Table 2 (Eldridge, 2023; Woodward et al., 2015). The search produced 791 articles.

Table 2. Search String.

Stage 2: Selection of the Articles

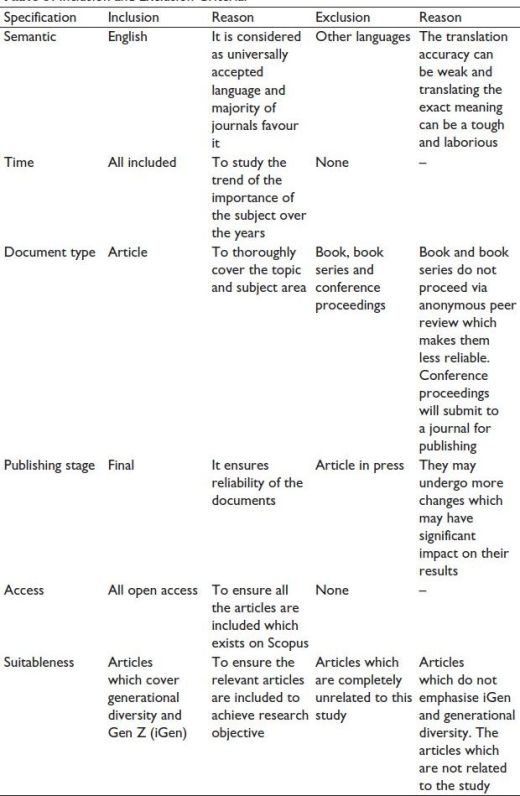

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the selection of the articles included document type and language. The details about the inclusion and exclusion criteria have also been given in Table 3. To keep the scope of this study wide we have not put any constraints on the years of the published articles. We came down to 215 articles after the selection of the articles stage.

Stage 3: Purification and Screening

In this stage of purification and screening, the articles are extracted on the basis of relevance for the study. The articles were screened in detail and selected the ones which are relevant considering the objectives of this research study. After the extraction of the outliers, 59 articles which were found to be relevant.

Discussion

This study focussed on 59 articles for the analysis purpose using TCCM framework. The descriptive analysis followed by the TCCM framework analysis has been discussed. The description for the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the research article is given in Table 3. The articles were selected on the basis of the language, type of document, publishing stage and suitability.

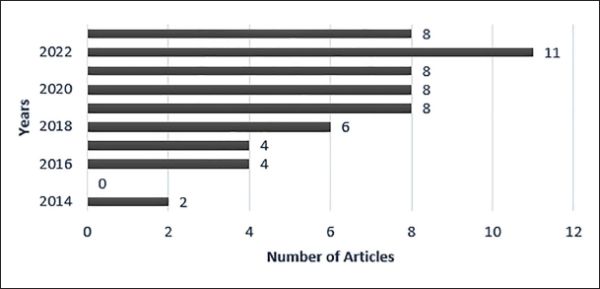

On the Basis of Time

The descriptive analysis shows us that the trend of research on the topics related to iGen and generational diversity has been increasing exponentially with time. The published articles range from 2014 to 2023 (till the month of July). The number of articles has been increasing to highest, that is, 11 articles in 2022 which can be seen clearly in Figure 1.

On the Basis of Place

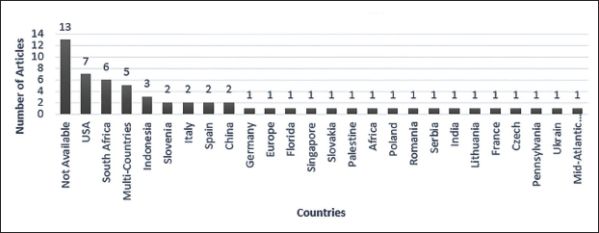

Our study shows that a large number of articles have not mentioned the country which was focussed in their study. However, the United States of America turned out to be the country where many researches focussing on either generational diversity or iGen or both have been conducted (n = 7). The detailed description about the studies taking place in numerous countries has been given in Figure 2.

On the Basis of the Industry

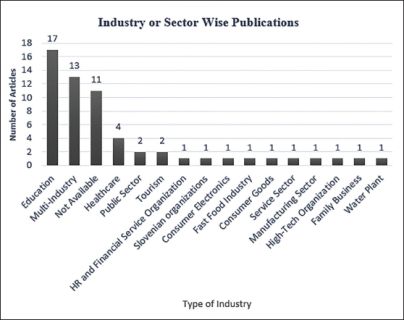

Our study indicates that a large number of studies were conducted in education sector or industry (n = 17). Following the trend and to ensure that the studies can be generalised, researchers have conducted their research considering multiple industries (n = 13). The details about the studies conducted in various industries over time have been depicted in Figure 3.

Table 3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria.

Figure 1. Year-wise publications.

Figure 2. Country-wise publications.

Analysis on the basis of TCCM Framework

TCCM categorises the research arena into four dimensions: theory, context, characteristic and methodology (Chauhan et al., 2021; Paul & Rosado-Serrano, 2019). This section highlights the theme which had been used to explore about the topic. It also showcases mainly in which context this topic has been studied, the characteristics such as the variables used and methodology adopted by researchers to achieve the objectives. This section also consists of the dimensions for the future research which will contribute in expanding the boundaries of the literature of the topic.

Figure 3. On the basis if industry: Industry or Sector-wise publications.

Theories

Theory is the first aspect which is studied while following the TCCM framework. It was discovered that various theories have been considered by the researchers depending upon the scope and context of the research study. However, theory of generations is anchored in the majority of the articles. Other theoretical arenas adopted by the researchers are social exchange theory, theory of plant behaviour and self-determination theory. The details about the theories that have been used in the various articles have been showcased in the supplementary material.

Theory of Generations.

The seminal work conducted by Mannheim (1952) indicates that generations are categorised on the basis of the common time of birth. Generational cohort theory also describes that the generations who are exposed to identical events and experiences will have identical set of characteristics and behavioural patterns (Inglehart, 1997).

Context

The sample of this research study indicates that the research was conducted in the developing countries and the developed countries regarding generational diversity, iGen or both. The research on these topics was were majorly conducted in the European continent (n = 17). However, on the country level, majority of the research studies were conducted focussing the population of USA (n = 7). Researchers have also focussed in conducting studies in the multi-countries (i.e. 5%) with the aim of generalising the results. The geographical context found to be missing from a significant number of studies (n = 13).

The results of this research study indicates that various industries and sectors have been focussed by the researchers like healthcare, public sector, manufacturing sector and family business. for conducting the research regarding the topic. It was found that education sector has been focussed the most for conducting the research (n = 17). About 22% of the sample studies have been conducted keeping multiple industries and sectors as the centre of attention.

The following themes were reflected in the research articles: intergenerational difference, generational diversity, sustainable human resource management, financial behaviour and tourism. The details about the contextual factors that have been focussed in the various articles has been showcased in the supplementary material.

Characteristics

Antecedent

The sample has been analysed and some of the recurring antecedents which were independent in nature came out to be demographic characteristics like age (Kaminska & Borzillo, 2018; Williams, 2016), gender, education (Nnambooze & Parumasur, 2016), social media marketing activities (Ruangkanjanases et al., 2022) and intergenerational perspective (Abu Daqar et al., 2020). The details about other antecedents are given in the supplementary material. iGen values have not been considered as antecedents yet which may impact their behaviour and actions in the workspaces. It may be considered for the further research studies.

Consequence

Our analysis indicated that some of the recurring outcomes among the sample of this study are values, behaviour (Qi et al., 2021; Ruangkanjanases et al., 2022), job satisfaction (Bachus et al., 2022; Jelenko, 2020; Tan & Chin, 2023), diversity, individualism and technology (Pichler et al., 2021). However, there are some of the consequences like ethical behaviour (Klopotan et al., 2020) and financial behaviour (Abu Daqar et al., 2020). which are context and industry dependent. The details about the remaining dependent variables are given in the supplementary material. Some of the outcomes like attitudes are unexplored in the literature of iGen related generational diversity.

Mediating, Moderating and Control Variables

Mediating variables are responsible to describe the relationship between antecedents and consequences (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Some of the mediating variables utilised by the researchers are brand equity (Ruangkanjanases et al., 2022), perceived space, lived space (Kangwa et al., 2021), overconfidence (Tsai et al., 2018) and so on. The details of the remaining existing mediating variables are given in the supplementary material. Demographic variables can be used to mediate the relationship between iGen characteristics and their impact in workspaces.

Moderating variables refer to the variables which dominates the direction and intensity of the relationship between antecedents and consequences (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Some of the moderating variables discussed are brand awareness (Ruangkanjanases et al., 2022), environmental factors (Urick et al., 2016) and self-efficacy of environmental protection (Zhao & An, 2023). The details are given in the supplementary material. Variables like demographic and behavioural have a scope to be studied as moderating variables.

The interconnection between generational diversity focussing iGen and the workspaces can be influenced by the control variables. Researchers highlighted some of the control variables like demographic factors such as age (Klopotan et al., 2020), gender (Figà-Talamanca et al., 2022; Qi et al., 2021; Rahadi et al., 2021), nationality and religion (Roman-Calderon et al., 2019; Tan & Chin, 2023). These factors may have a notable impact on shaping the value system, personality and behavioural patterns of iGen.

Methodology

The results reflect that majority of the studies were conducted with the quantitative approach (n = 29). Followed by the research studies which were conducted with the qualitative approach (n = 20). Some of the researchers also adopted mixed approach to enhance the accuracy level of the outcomes obtained.

Researchers utilised the primary or the secondary data sources or both to gather the data for their research study. Methods like survey, focus groups and systematic literature review were seen to be used by the researchers. Survey and interview methods were found to be most used methods during the data gathering process.

Probability and non-probability sampling techniques both were adopted by the researchers. The analysis indicates that the sampling techniques like purposive, snowball, nested sampling and stratified sampling were utilised in the sample articles. The details about the various sampling and research designs have been showcased in the supplementary material.

Conclusion

On the basis of the analysis, the conclusion can be made that there is still scope to study generational diversity by adding iGen to the mix of demographic population of the organisations. Studies on iGen and generational diversity exist in the literature but there is an evident gap in combining these two constructs and studying them in the organisational setting.

Implications

iGen is expected to enter the workspaces soon. Some of them have already joined the organisations and a majority of them will soon be a part of the organisations (Pichler et al., 2021; Schroth, 2019). Generational diversity implies that all the generations are unique. Their exposure and their surrounding contribute towards their value system, priorities and their perception towards the organisations. It is essential for the organisations to understand this generation to fascinate, charm, satisfy and keep their iGen employees. Many researchers have been studying about generational cohorts from a long time. The generations are found to be similar in some aspects but unique in another. The various facets of previous generations have been studied in great detail (Gabrielova & Buchko, 2021). This article adds another generational cohort, that is, iGen to the mix in order to broaden the scope of generation-based studies. Studying this generational cohort is important because this generation will take a majority of positions in the workspaces soon (Francis & Hoefel, 2018; Gabrielova & Buchko, 2021). It is expected that they will impact the organisations and the world. It is important to study the iGen because the future of the society will be in the hands of this generation.

Limitations

While we tried making this review study meaningful and relevant for the researchers but it was not free from a few shortcomings: (a) only TCCM framework has been used for this SLR, (b) the database utilised in the acquisition stage was limited to Scopus, (c) limited and most occurred in articles keywords were used in the acquisition stage (Table 2), (d) the inclusion and exclusion criteria put constraints on the sample.

Future Scope

The study aimed at locating the research gaps and the scope for further research. Some of the limitations of this review study opened the paths for the future researchers. (a) Other methods like bibliometric analysis can be used to further identify the gaps which might have left due to the scope and limitations of TTCM. (b) Other databases like WOS and EBSCO can be used for the future research. (c) More keywords can be added to the keyword combination. (d) The inclusion and exclusion criteria pave the way for further research. They may have a substantial impact on the conclusion. (e) After a span of time, the need for a review study crops up due to the additional contribution of the researchers in the field.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this article is available online.

ORCID iD

Sonali Jain  https://orcid.org/0009-0004-8250-4866

https://orcid.org/0009-0004-8250-4866

Abu Daqar, M., Arqawi, S., & Abu Karsh, S. (2020). Fintech in the eyes of Millennials and Generation Z (the financial behavior and Fintech perception). Banks and Bank Systems, 15(3), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.21511/bbs.15(3).2020.03

Akçay, T. (2022). Neil Howe–William Strauss, The Millennials rising: The next great generation. Vintage Books.

Ali.png) , A.,

, A., .png) injarevi

injarevi.png) , M., & Maktouf-Kahriman, N. (2022). Exploring the antecedents of masstige purchase behaviour among different generations. Management & Marketing. Challenges for the Knowledge Society, 17(3), 255–271. https://doi.org/10.2478/mmcks-2022-0014

, M., & Maktouf-Kahriman, N. (2022). Exploring the antecedents of masstige purchase behaviour among different generations. Management & Marketing. Challenges for the Knowledge Society, 17(3), 255–271. https://doi.org/10.2478/mmcks-2022-0014

Amayah, A. T., & Gedro, J. (2014). Understanding generational diversity: Strategic human resource management and development across the generational ‘divide’. New Horizons in Adult Education and Human Resource Development, 26, 36–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/nha3.20061

Armmer, F. (2017). An inductive discussion of the interrelationships between nursing shortage, horizontal violence, generational diversity, and healthy work environments. Administrative Sciences, 7(4), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci7040034

Bachus, V., Dishman, L., & Fick, J. W. (2022). Improving workforce experiences at United States federally qualified health centers: Exploring the perceived impact of generational diversity on employee engagement. Patient Experience Journal, 9(2), 17–30. https://doi.org/10.35680/2372-0247.1715

Ballone, C. (2007). Consulting your clients to leverage the multi-generational workforce. Journal of Practical Consulting, 2(1), 9–15.

Baran, M., & K.png) os, M. (2014). Managing an intergenerational workforce as a factor of company competitiveness. Journal of International Studies, 7(1), 94–101. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-8330.2014/7-1/8

os, M. (2014). Managing an intergenerational workforce as a factor of company competitiveness. Journal of International Studies, 7(1), 94–101. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-8330.2014/7-1/8

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. Retrieved, 10 January 2022, from https://psycnet.apa.org/buy/1987-13085-001

Bejtkovsky, J. (2016). The employees of baby boomers generation, Generation X, Generation Y and Generation Z in selected Czech corporations as conceivers of development and competitiveness in their corporation. Journal of Competitiveness, 8(4), 105–123. https://doi.org/10.7441/joc.2016.04.07

Bornman, D. A. J. (2019). Gender-based leadership perceptions and preferences of Generation Z as future business leaders in South Africa. Acta Commercii, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.4102/ac.v19i1.708

Chauhan, S., Akhtar, A., & Gupta, A. (2021). Gamification in banking: A review, synthesis and setting research agenda. Young Consumers, 22(3), 456–479.

Closson, K., Prakash, R., Javalkar, P., Beattie, T., Thalinja, R., Collumbien, M., Ramanaik, S., Isac, S., Watts, C., Moses, S., Gafos, M., Heise, L., Becker, M., & Bhattacharjee, P. (2023). Adolescent girls and their family members’ attitudes around gendered power inequity and associations with future aspirations in Karnataka, India. Violence Against Women, 29(5), 836–859. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778012221097142

Dangelico, R. M., & Pontrandolfo, P. (2010). From green product definitions and classifications to the Green Option Matrix. Journal of Cleaner Production, 18(16–17), 1608–1628.

Deas, A., & Coetzee, M. (2022). A value-oriented psychological contract: Generational differences amidst a global pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 921184.

De Toro, I. S., Labrador-Fernández, J., & De Nicolás, V. L. (2019). Generational diversity in the workplace: Psychological empowerment and flexibility in Spanish companies. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1953. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01953

Eldridge, A. (2023). Generation Z. Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Figà-Talamanca, G., Tanzi, P. M., & D’Urzo, E. (2022). Robo-advisor acceptance: Do gender and generation matter? PLoS ONE, 17(6), e0269454. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269454

Fobian, D., & Maloa, F. (2020). Exploration of the reward preferences of generational groups in a fast-moving consumer goods organisation. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 18. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v18i0.1244

Francis, T., & Hoefel, F. (2018). ‘True Gen’: Generation Z and its implications for companies. McKinsey & Company, 12, 1–10.

Fry, R. (2018). Millennials are the largest generation in the US labor force. Pew Research Center.

Gabrielova, K., & Buchko, A. A. (2021). Here comes Generation Z: Millennials as managers. Business Horizons, 64(4), 489–499.

Ganguli, R., Padhy, S. C., & Saxena, T. (2022). The characteristics and preferences of Gen Z: A review of multi-geography findings. IUP Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(2), 79–98.

Haynes, B. P. (2011). The impact of generational differences on the workplace. Journal of Corporate Real Estate, 13(2), 98–108. https://doi.org/10.1108/1463001111/1136812

Heyns, M. M., & Kerr, M. D. (2018). Generational differences in workplace motivation. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 16. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v16i0.967

Heyns, E. P., Eldermire, E. R. B., & Howard, H. A. (2019). Unsubstantiated conclusions: A scoping review on generational differences of leadership in academic libraries. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 45(5), 102054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2019.102054

Howe, N., & Strauss, W. (1992). The new generation gap. Atlantic Boston, 270, 67.

Inglehart, R. (1997). Modernisation and postmodernisation: Cultural, economic, and political change in 43 societies. Princeton University Press.

Ingusci, E. (2018). Diversity climate and job crafting: The role of age. The Open Psychology Journal, 11(1), 105–111. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874350101811010105

Jain, S. K., & Kaur, G. (2006). Role of socio-demographics in segmenting and profiling green consumers: An exploratory study of consumers in India. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 18(3), 107–146.

Jelenko, J. (2020). The role of intergenerational differentiation in perception of employee engagement and job satisfaction among older and younger employees in Slovenia. Changing Societies & Personalities, 4(1), 68–90. https://doi.org/10.15826/csp.2020.4.1.090

Joshi, A., Dencker, J., Franz, G., & Martocchio, J. (2010). Unpacking generational identities in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 35, 392–414.

Jung, S. H., Jung, Y. S., & Yoon, H. H. (2021). COVID-19: The effects of job insecurity on the job engagement and turnover intent of deluxe hotel employees and the moderating role of generational characteristics. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 92, 102703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102703

Kaminska, R., & Borzillo, S. (2018). Challenges to the learning organization in the context of generational diversity and social networks. The Learning Organization, 25(2), 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1108/TLO-03-2017-0033

Kangwa, D., Mwale, J. T., & Shaikh, J. M. (2021). The social production of financial inclusion of Generation Z in digital banking ecosystems. Australasian Business, Accounting and Finance Journal, 15(3), 95–118. https://doi.org/10.14453/aabfj.v15i3.6

Klopotan, I., Aleksi.png) , A., & Vinkovi

, A., & Vinkovi.png) , N. (2020). Do business ethics and ethical decision making still matter: Perspective of different generational cohorts. Business Systems Research Journal, 11(1), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.2478/bsrj-2020-0003

, N. (2020). Do business ethics and ethical decision making still matter: Perspective of different generational cohorts. Business Systems Research Journal, 11(1), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.2478/bsrj-2020-0003

Lasthuizen, K., & Badar, K. (2023). Ethical reasoning at work: A cross-country comparison of gender and age differences. Administrative Sciences, 13(5), 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13050136

Malele, V. (2020). Demystifying entrepreneurship and innovation to prepare Generation Z for possibilities of self-employment. Journal of Engineering Education Transformations, 34(1), 70. https://doi.org/10.16920/jeet/2020/v34i1/151592

Mannheim, K. (1952). The problem of generations. Essays on the sociology of knowledge (pp. 276–322). Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Mannheim, K. (1993). El problema de las generaciones. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 62, 193–242.

Marschalko, E. E., Szabo, K., Kotta, I., & Kalcza-Janosi, K. (2022). The role of positive and negative information processing in COVID-19 vaccine uptake in women of Generation X, Y, and Z: The power of good is stronger than bad in youngsters? Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 925675. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.925675

Mejía-Manzano, L. A., Sirkis, G., Rojas, J.-C., Gallardo, K., Vázquez-Villegas, P., Camacho-Zuñiga, C., Membrillo-Hernández, J., & Caratozzolo, P. (2022). Embracing thinking diversity in higher education to achieve a lifelong learning culture. Education Sciences, 12(12), 913. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120913

Nguyen, T. L., Huynh, M. K., Ho, N. N., Le, T. G. B., & Doan, N. D. H. (2022). Factors affecting of environmental consciousness on green purchase intention: An empirical study of Generation Z in Vietnam. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 9(1), 333–343.

Nnambooze, B. E., & Parumasur, S. B. (2016). Understanding the multigenerational workforce: Are the generations significantly different or similar? Corporate Ownership and Control, 13(2), 224–257. https://doi.org/10.22495/cocv13i2c1p4

Pangestu, S., & Karnadi, E. B. (2020). The effects of financial literacy and materialism on the savings decision of Generation Z Indonesians. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1743618. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1743618

Parry, E., & Urwin, P. (2017). The evidence base for generational differences: Where do we go from here? Work, Aging and Retirement, 3(2), 140–148. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waw037

Paul, J., & Rosado-Serrano, A. (2019). Gradual internationalization vs born-global/international new venture models: A review and research agenda. International Marketing Review, 36(6), 830–858.

Paunovic, I., Müller, C., & Deimel, K. (2023). Citizen participation for sustainability and resilience: A generational cohort perspective on community brand identity perceptions and development priorities in a rural community. Sustainability, 15(9), 7307. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097307

Pichler, S., Kohli, C., & Granitz, N. (2021). DITTO for Gen Z: A framework for leveraging the uniqueness of the new generation. Business Horizons, 64(5), 599–610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2021.02.021

Poisat, P., Mey, M. R., & Sharp, G. (2018). Do talent management strategies influence the psychological contract within a diverse environment? SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 16. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v16i0.1044

Portela Pruaño, A., Bernárdez Gómez, A., Marrero Galván, J. J., & Nieto Cano, J. M. (2022). Intergenerational professional development and learning of teachers: A mixed methods study. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 21, 160940692211332. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069221133233

Prund, C. (2021). Why Generation Z is redefining the HRM processes. Studies in Business & Economics, 16(3), 190–199.

Qi, W., Li, L., & Zhong, J. (2021). Value preferences and intergenerational differences of tourists to traditional Chinese villages. Discrete Dynamics in Nature and Society, 2021, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/9059164

Rahadi, R. A., Putri, N. R. R., Soekarno, S., Damayanti, S. M., Murtaqi, I., & Saputra, J. (2021). Analyzing cashless behavior among Generation Z in Indonesia. International Journal of Data and Network Science, 5(4), 601–612. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.ijdns.2021.8.007

Robertson, D. N., & Dasoo, N. (2019). The mobile learning conscious tutor: Incorporating Facebook in tutorials. Journal of Education, 76. https://doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i76a08

Robinson, L. (2016). Age difference and face-saving in an inter-generational problem-based learning group. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 40(4), 466–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2014.984598

Roman-Calderon, J. P., Gonzales-Miranda, D. R., García, G. A., & Gallo, O. (2019). Colombian Millennials at the workplace. Evidence-Based HRM: A Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship, 7(3), 249–261. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBHRM-04-2018-0029

Rožman, M., Treven, S., & ?an?er, V. (2020). The impact of promoting intergenerational synergy on the work engagement of older employees in Slovenia. JEEMS Journal of East European Management Studies, 25(1), 9–34.

Ruangkanjanases, A., Sivarak, O., Wibowo, A., & Chen, S.-C. (2022). Creating behavioral engagement among higher education’s prospective students through social media marketing activities: The role of brand equity as mediator. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1004573. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1004573

Ryder, N. B. (1965). The cohort as a concept in the study of social change. American Sociological Review, 30, 843–861. https://doi.org/10.2307/2090964

Rzemieniak, M., & Wawer, M. (2021). Employer branding in the context of the company’s sustainable development strategy from the perspective of gender diversity of Generation Z. Sustainability, 13(2), 828. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020828

Sánchez-Hernández, M. I., González-López, Ó. R., Buenadicha-Mateos, M., & Tato-Jiménez, J. L. (2019). Work-life balance in great companies and pending issues for engaging new generations at work. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(24), 5122. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16245122

Savanevi.png) ien

ien.png) , A., Statnick

, A., Statnick.png) , G., & Vaitkevi

, G., & Vaitkevi.png) ius, S. (2019). Individual innovativeness of different generations in the context of the forthcoming society 5.0 in Lithuania. Engineering Economics, 30(2), 211–222. https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.ee.30.2.22760

ius, S. (2019). Individual innovativeness of different generations in the context of the forthcoming society 5.0 in Lithuania. Engineering Economics, 30(2), 211–222. https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.ee.30.2.22760

Schmidt, X., & Muehlfeld, K. (2017). What’s so special about intergenerational knowledge transfer? Identifying challenges of intergenerational knowledge transfer. Management Revue, 28(4), 375–411. https://doi.org/10.5771/0935-9915-2017-4-375

Schroth, H. (2019). Are you ready for Gen Z in the workplace? California Management Review, 61(3), 5–18.

Shah, V., & Shah, A. (2018). Relationship between student perception of school worthiness and demographic factors. Frontiers in Education, 3, 45. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2018.00045

Singh, V., Verma, S., & Chaurasia, S. (2021). Intellectual structure of multigenerational workforce and contextualizing work values across generations: A multistage analysis. International Journal of Manpower, 42(3), 470–487. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-04-2019-0207

Smola, W. K., & Sutton, C. D. (2002). Generational differences: Revisiting generational work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(4), 363–382.

Strauss, W., & Howe, N. (1991). Generations: The history of America’s future, 1584 to 2069.

Talmon, G. A., Nasir, S., Beck Dallaghan, G. L., Nelson, K. L., Harter, D. A., Atiya, S., Renavikar, P. S., & Miller, M. (2022). Teaching about intergenerational dynamics: An exploratory study of perceptions and prevalence in US medical schools. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 13, 113–119. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S329523

Tan, S. H. E., & Chin, G. F. (2023). Generational effect on nurses’ work values, engagement, and satisfaction in an acute hospital. BMC Nursing, 22(1), 88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-023-01256-2

T?nase, M. O., Nistoreanu, P., Dina, R., Georgescu, B., Nicula, V., & Mirea, C. N. (2023). Generation Z Romanian students’ relation with rural tourism—An exploratory study. Sustainability, 15(10), 8166. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108166

Tran, Y. (2019). Computational thinking equity in elementary classrooms: What third-grade students know and can do. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 57(1), 3–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633117743918

Tsai, F.-S., Lin, C.-H., Lin, J. L., Lu, I.-P., & Nugroho, A. (2018). Generational diversity, overconfidence and decision-making in family business: A knowledge heterogeneity perspective. Asia Pacific Management Review, 23(1), 53–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2017.02.001

Urick, M. J., Hollensbe, E. C., Masterson, S. S., & Lyons, S. T. (2016). Understanding and managing intergenerational conflict: An examination of influences and strategies. Work, Aging and Retirement, waw009. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waw009

Van Lith, T., Cheshure, A., Pickett, S. M., Stanwood, G. D., & Beerse, M. (2021). Mindfulness based art therapy study protocol to determine efficacy in reducing college stress and anxiety. BMC Psychology, 9(1), 134. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00634-2

Verlinden, N. (n. d.). Millennials vs. Gen Z: How do they achieve success in the workplace? https://www.aihr.com/blog/millennials-vs-gen-z/

Vitvitskaya, O., Suyo-Vega, J. A., Meneses-La-Riva, M. E., & Fernández-Bedoya, V. H. (2022). Behaviours and characteristics of digital natives throughout the teaching-learning process: A systematic review of scientific literature from 2016 to 2021. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 11(3), 38. https://doi.org/10.36941/ajis-2022-0066

Vlastelica, T., Kosti?-Stankovi?, M., Krsti?, J., & Raji?, T. (2023). Generation Z’s intentions towards sustainable clothing disposal: Extending the theory of planned behavior. Polish Journal of Environmental Studies, 32(3), 2345–2360. https://doi.org/10.15244/pjoes/157007

Vra.png) aková, N., Gyurák Babe

aková, N., Gyurák Babe.png) ová, Z., & Chlpeková, A. (2021). Sustainable human resource management and generational diversity: The importance of the age management pillars. Sustainability, 13(15), 8496. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158496

ová, Z., & Chlpeková, A. (2021). Sustainable human resource management and generational diversity: The importance of the age management pillars. Sustainability, 13(15), 8496. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158496

Williams, M. (2016). Being trusted: How team generational age diversity promotes and undermines trust in cross-boundary relationships: Does team generational diversity influence dyadic trust? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(3), 346–373. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2045

Woodward, I., Vongswasdi, P., & More, E. (2015). Generational diversity at work: A systematic review of the research [INSEAD Working Paper No. 2015/48/OB]. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2630650

Zehetner, A., Zehetner, D., Lepeyko, T., & Blyznyuk, T. (2022, November). Generation Z’s expectations of their leaders: A cross-cultural, multi-dimensional investigation of leadership styles. ECMLG 2022 18th European conference on management, leadership and governance. Academic Conferences and Publishing Limited.

Zhao, X., & An, H. (2023). Research on the mechanism of heterogeneous corporate environmental responsibility in Z-generation consumers’ sustainable purchase intention. Sustainability, 15(13), 10318. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310318

Zhou, Y., He, T., & Lin, F. (2022). The digital divide is aging: An intergenerational investigation of social media engagement in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12965. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912965

Zilberstein, S., Lamont, M., & Sanchez, M. (2023). Recreating a plausible future: combining cultural repertoires in unsettled times. Sociological Science, 10, 348–373. https://doi.org/10.15195/v10.a11