1Department of Business Administration, Ravenshaw University, Cuttack, Odisha, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

Higher education institutions (HEIs) are under growing pressure to raise the standard of education they offer and to be more creative. Institutional accreditation acts as a quality control to make sure that institutions stay true to their mission and continue to benefit students academically. Accreditation has undergone major adjustments. As a per recent changes in higher education, the educational institutions and other bodies are rethinking how to demonstrate academic excellence to students who may not be participating in the traditional collegiate experience. Because of the pandemic, higher education had to quickly switch to a new approach to instruction, delivery, assessment and community engagement. These universities were able to experiment with new degrees of innovation while maintaining a high standard of quality through online and remote learning which justifies the need and motivation for this research. The article begins by outlining the increasingly varied spectrum of higher education stakeholders, including students, academicians and other interested parties, which has given rise to concerns about the quality of education and institution building. The relevance of leadership, governance, institution building and quality assurance in HEIs for accreditation requires properly carrying out its role as discussed in the later part of the article. The article is based on an extensive review of the accreditation system in India and summarises the implication of governance, leadership, quality assurance and institution building for better ratings. As the accreditation system is evolving with time, there lies a scope for future research.

Leadership, governance, higher education institutions, quality assurance, stakeholders, accreditation

Indian higher education is completely regulated. It's very difficult to start a private university. It's very difficult for a foreign university to come to India. As a result of that, our higher education is simply not keeping pace with India's demands. That is leading to a lot of problems which we need to address.

—Nandan Nilekani

There was a time when bright people had few prospects for higher education and good jobs here. But that is changing. India is no longer seen as an undesirable place to work or pursue research.

—Shashi Tharoor

Introduction

Advanced education is vital for social, profitable, artistic, scientific and political development. Education enables individuals to change from being mortal beings to enjoying mortal coffers. To foster invention, gift, rigidity and an exploration mindset in the current setting of globalisation, high-quality advanced education is needed. It is pivotal to make sure that education is upholding the minimum criteria necessary to satisfy the constantly shifting conditions across the globe in order to completely use its results. A nation’s advanced education system is estimated using delegation, a potent quality assurance instrument. An accredited academy or programme passes a rigorous process of external peer evaluation grounded on destined criteria or principles and conforms with the minimal conditions. Accreditation is regarded as a quality seal. In a country like India, which is the reflection of a society full of diversity, distinct testaments and varied contemporary opinions, the conception of advanced education has different effects on different people. The pluralism of views is relatively ineluctable; some would comment that it should be like that only. Still, as we intend to bandy and learn further about quality in advanced education, we should ask ourselves: What is advanced in advanced education? You, as a schoolteacher/stakeholder of advanced education, will agree that it is not just about the advanced position of educational structure in the country. There is more to the story. Regarding the position, advanced education encompasses university and council tutoring programmes for literacy development as students work to get advanced educational credentials. To progress students to new frontiers of knowledge in various fields of endeavour, advanced education gives in-depth knowledge and comprehension (subject disciplines). The twenty-first century has begun with an explosion in the number of advanced education scholars. According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), registration for advanced education has increased roughly from 72 million in 1999 to 133 million in 2004. Banning North America and Western Europe, registration for advanced education in the rest of the world further than doubled in those five years, with an increase from 41.1 million to 99.1 million. China alone increased its share from 6.4 million in 1999 to 19.4 million in 2004, giving it the largest advanced education registration in the world. It further increased to 23 million in 2005. This massive expansion is taking place for at least two reasons: first, an increase in social demand for advanced education; and second, an increase in the profitable need for furthering largely educated mortal coffers. In the case of India, the deficit of professed manpower is a cause for concern in utmost sectors. Experts admit that the present advanced education system in India is not equipped to address this problem without some changes in the introductory structure that includes governance and leadership. Official records show that the gross registration rate in advanced education is only 11%, while the National Knowledge Commission says only 7% of the population between the age group of 18 and 24 registers for advanced education. In addition, those who have access to advanced education are not assured of quality education. Despite having over 300 universities, not a single Indian university is listed in the top 100 universities of the world. The increase in social demand for advanced education is a result of the following five factors:

The National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC) oversees institutional position, evaluation and delegation in India. In July 2017, NAAC streamlined its frame for quality and excellence in health care and added a Quality Indicator Framework (QIF) with criteria that combine quantitative data (72 weightage) and qualitative data (28 weightage) (NAAC, 2013). Table 1 displays a comparison of NAAC’s new fashion and old approach.

Research Methodology

The current article is a theoretical review, which comes from various secondary sources such as research articles in journals, books, newspapers and websites of accreditation bodies. It is basically a content review article on the accreditation system in higher education institutions (HEIs) in the Indian context.

Source: NAAC Institutional Manual for Self-Study Report Universities (http://naac.gov.in/index.php/en/assessment-accreditation#accreditation).

Accreditation: Concept and Purpose

Accreditation of HEIs reflects ‘Quality’, the dictionary meaning of accreditation is ‘official recognition, guarantee of quality and general acceptance’. A higher education institution’s academic programmes and staff-related services are evaluated by an outside organisation known as the accreditation body or accreditation agency as part of the accreditation process, which is a type of quality assurance procedure that determines whether the higher education institution satisfies applicable standards. The accreditation authority or agency grants the institution accredited status if it satisfies the necessary requirements. The accreditation agency primarily evaluates institutional criteria such as governance, leadership and management; programme, course and subject/module specifications; curriculum; teaching, learning and assessment; research, consultancy, training; student support and student progression; innovation and best practices; and learning resources and infrastructure.

A regulating authority, commission under the higher education minister or an international organisation would have made the decisions regarding the criteria relating to the minimum relevant standards for all the institutions. Depending on the agency, the certification process might take from 6 to 18 months. The methods and process for accreditation differ. Academicians selected by the accreditation body, who are experienced in accreditation processes and who are drawn from several reputable schools, carry out the accreditation process. Higher education institutions use accreditation to communicate to all of their stakeholders—students, parents, recruiters, alumni, staff, administration and the governing body—the calibre of their educational processes. Accreditation helps higher education institutions to market their programmes nationally and internationally. In most countries around the world, the function of accreditation for higher education institutions is conducted by government institutions, such as the ministry of education or the department of higher education in the human resources development ministry. In India, the NAAC is an institution that assesses and accredits institutions of higher education. It is an autonomous body funded by the University Grants Commission (UGC) of Government of India, headquartered in Bangalore. The National Board of Accreditation (NBA), India, was initially established by All India Council of Technical Education (AICTE), which undertakes periodic evaluations of technical institutions and programmes according to specified norms and standards as recommended by AICTE.

Accreditation’s main goal is to ensure quality assurance and control, frequently in relation to a certification system in the fields of education, training, testing, etc. This duty is carried out by a ministry of education agency in some nations, but it is carried out by a coalition of nonprofit organisations or professional associations in many industrialised nations. There is currently no institution in our nation that unifies the bulk of professional societies under one umbrella. However, there are a number of quality control (inspection) procedures in place, including university affiliation, acceptance by professional associations like the Institution of Engineers, and AICTE clearance for new and existing programmes. Accreditation will also ensure: (a) quality control (minimum standards) in HEIs, (b) accountability and transparency, (c) quality enhancement and (d) the facilitation of student mobility. Higher education’s compliance with minimal standards for quality in terms of inputs, processes and results is ensured by quality control. There are concerns about quality owing to the higher education sector’s rapid growth and the education provider’s diversity. In order to maintain national development objectives and stakeholder interests, these basic standards urgently need to be checked.

In order to assure ‘value for the money’, or accountability through results evidence, stakeholders are encouraged to support accreditation, which is commissioned by a reputable and recognised body. Transparency in the way the higher education system operates is provided via the accreditation process. Through the certification process, deficiencies are found, allowing the system to adopt remedies and raise standards. Accreditation fosters competition, which contributes to higher quality. The reciprocal acceptance of credentials, which depends on the breadth of the certification, is crucial in the globalised economy and permits institutional, regional, national and worldwide student mobility.

However, there are several differences between the functions of inspection and accreditation that people always misinterpret; these are brought out in Table 2.

The academicians and other entities must answer and internalise the following questions in accreditation of higher education:

Accreditation for Quality Assurance

The most popular technique for external quality assurance is accreditation. It is the result of a procedure by which a governmental, institutional or private body (accreditation agency) assesses the quality of an HEI as a whole, or a specific higher education programme course, in order to formally recognise it as having met certain predetermined criteria or standards and award a quality label. According to the institution’s mission, the goals of the programme(s) and the expectations of many stakeholders, including students and professors, accreditation guarantees a particular degree of quality. A recognised status (yes/no, a score on a scale of 1 to 10, a letter grade and a score combined, an operating licence or conditional deferred recognition) is typically awarded as a result of the entire procedure. The following factors have made the adoption of accreditation desirable for quality assurance today:

The Definition of Quality: Fitness for Purpose and Standard-Based Quality

The stakeholders in higher education are many and varied. Accordingly, the concept of quality also varies. We have identified 10 definitions of quality: providing excellence, being exceptional, providing value for money, conforming to specifications, getting things right the first time, meeting customers’ needs, having zero defects, providing added value, exhibiting fitness of purpose and exhibiting fitness for purpose. The concept of quality has also evolved over time.

According to Gola (2023), quality as applied to higher education by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) could be ‘specifying worthwhile learning goals and enabling students to achieve them’. Specifying worthwhile learning goals would involve articulating academic standards to meet: (a) society’s expectations; (b) students’ aspirations; (c) the demands of the government, business and industry; and (d) the requirements of professional institutions. Enabling students to achieve these goals would require good course design, an effective teaching/learning strategy, competent teachers and an environment that enables learning.

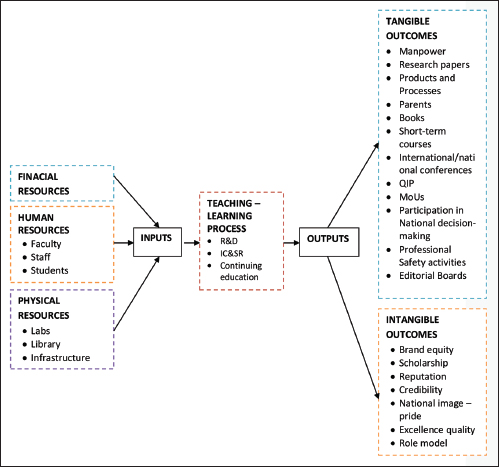

The relevance (fitness of purpose) of higher education’s mission and objectives for the relevant stakeholder(s) as well as the degree to which the institution/programme/course satisfies the mission and objectives (fitness for purpose) are factors in its quality. The standard-based approach to quality refers to how well an institution, programme or course satisfies the minimum standards established for inputs, procedures and outcomes. Evaluation or assessment of various subsystems and component processes is the fundamental step in the accreditation process. There are two parts to it: critical self-assessment and external peer review, where the former is performed by the faculty as a part of the support materials and, if carefully and effectively done, can be a valuable strategic tool. The proposed process is depicted in the following Figure 1.

The major objectives of the teaching-learning process are as follows:

Table 3 and Table 4 summarise the quality policy and quality services at various levels and their implementation. Table 5 shows the action plans and institutional strategies at various operational processes. Table 6 showcases the institute interaction with all its stakeholders. All of these help in building institutional leadership.

Proper support is required for policy and planning through need analysis, research inputs and consultations with the stakeholders for building institutional leadership. The institutional leadership supports the faculty by providing adequate funding and by creating policies that are appropriate for addressing the needs of students, including those related to admission, attendance at classes, following the curriculum, writing exams and earning high marks, preparing for competitions, overcoming obstacles, landing a job and advancing in their careers. It also helps faculties develop appropriate policy to deal with societal issues by engaging in research activities and inputs, and coming up with solutions that best address issues in business, information and communication technology, management and social work. By comprehending the changing demands of the job market, adjustments to the curriculum and provision of consulting services, it also aids in the development of appropriate policies to solve the sector’s most pressing problems. The institutional leadership is responsible for strengthening the excellence culture by establishing spiritual forums, literary forums, yoga and mind control programmes, training sessions and personality development programmes, academic pursuit through research centres and reinforcing discipline. Departmentalisation, decentralisation, information exchange, technology development, infrastructure development, the admissions process and academic leadership are all aspects of institutional leadership involved in institutional change.

Procedure Adopted for Institution Building

Procedures are set by an institution to periodically review and evaluate the effectiveness of the institution’s plans and policies for effective implementation. To monitor and assess the institute’s plans and policies, the following techniques are used:

The academic leadership provided to the faculty by the top management are as follows:

1. Set standards: The faculty members are allowed to constitute desired levels of knowledge and prepare the students accordingly.

2. Measuring performance:

3. Enforcing discipline:

4. Imbibing values: The value system of an institution as reflected in the vision admission of the institution is translated into action through imbibing values among the students.

5. Character formation: The faculty members who works closely with the students to influence their character formation such as gender sensitivity, religious tolerance, linguistic and geographical integration, and moral integrity.

6. Personality building: Provision of skill development programmes that will be offered in addition to regular classes that would build their capacity for communication, language comprehension, self-esteem, emotional intelligence, dignity and appeal.

Leadership, Governance and Accreditation

In order to fulfil the institution’s vision, mission and goals as well as to create a positive institutional culture, leadership through defining values and a participatory decision-making process are essential. The institutional efforts to realise its vision are reflected in the formal and informal procedures to coordinate academic and administrative planning and implementation. The institution’s goal for the duration of the strategic plan is outlined in the vision statement. The specific traits or qualities that will characterise the institutions in their idealised state are outlined in vision statements. The vision statement is regarded as attainable and is used to motivate and inspire. A purpose statement is all that the mission statement is. It explains in one or two sentences what the institution seeks to accomplish, why it exists and what ultimate result should be expected. Language in the mission statement is usually expressed using verbs in the infinitive (to increase, to improve, etc.) and also should identify any problems or conditions that will be changed. Gap analysis is a procedure to assess the ‘gap’ between the institution’s current status and specific features of the vision of the institution. It also identifies what actions need to be taken to close the gap and can be studied through SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) analysis. SWOT is used as a framework for the environmental scan.

The process enables planners to provide more information to support the gap analysis of the strategic plan’s activities that must be implemented to help the institution achieve its vision. The environmental scan gathers data that is generic in nature and gives planners at the institution a shared understanding of trends and challenges for the future so that they can create a vision. The environmental scan serves as the foundation for institution-wide future-focused conversations. Unless those tendencies are observed to be developing into greater problems, a good environmental scan does not attempt to produce thorough data or market research, and it does not employ projections based on present trends. The institution’s vision is informed by the scan, which also identifies the broad strategic goals that will serve as a road map for an action plan. The internal environment and the external environment are the two main parts of an environmental scan. Both should be investigated to see if institution members share a common outlook on the future and what resources they think they have or will require going forward. To meet the necessary social commitment, the higher education sector must protect the interest of its consumers (i.e., students, employers in government and industry, society at large and also the institutions themselves). This phenomenon has generated a growing concern worldwide regarding the quality of higher education inputs, processes and outcomes. Now, new quality assurance systems are emerging to facilitate the HEIs. The following section clarifies what we mean by quality.

Institutional Strategy to Groom Leadership and Governance

Institutions can also inculcate different levels of leadership in students as well as in teachers as shown in Table 7 and Table 8. The various ways of inculcating the leadership at the student level is given in Table 7 and at the faculty level in Table 8. Table 9 shows how departments of an institution can work towards an effective decentralised governance system.

From the above sections, it is evident that the necessity to guarantee the quality of higher education has increased as a result of HEI expansion, privatisation and globalisation. Measurable outputs are produced as a result of the accrediting procedure. Many worldwide ranking bodies further assess the outcomes/results. National Institutional Ranking Framework (under the ministry of HRD, Government of India) conducts a ranking survey each year. The accreditation and rankings support HEIs’ efforts to promote a culture of research and innovation, publish research findings in peer-reviewed journals, and participate in conferences and workshops with research papers. Regular external expert evaluation of diverse processes and outcomes yields quantifiable results from such actions. Parents and students feel more secure knowing that the degree has some worth. This leads to an improvement in student success, including the achievement of learning objectives, graduation rates, greater career advancement through credit transfer and increased employability. Industry–academia tie-ups strengthen the curriculum to cover the gap between employment available in the market and skills obtained by the students. Accreditation procedures have an impact on the curriculum, instructor quality and the evaluation of learning outcomes. In reality, practically all accrediting processes now include these as necessary criteria.

Figure 1. Input–Output System in Educational Institutions.

Conclusion

The service division has adopted the idea of quality from the manufacturing strategy. It is interesting to note that there is a significant rise in demand for quality and excellence in the service sector. Numerous researchers have used various models to define the term ‘excellence’. Stakeholder satisfaction, attainment of learning objectives and student success are common elements in all models. Accreditation is seen as a tool for enabling high-quality education, a means of enhancing non-academic services, system transparency and establishing accountability at the proper levels. Advantages of accreditation are evident in the credit transfer of students from one accredited institution to another, the higher acceptance of degrees for further study around the globe, comparisons with other institutions and adoption of best practises, ongoing process improvements, the availability of funding, etc. Effects on these factors are interconnected and may require rethinking how HEIs operate. Thus, we can conclude that, reinforcing the culture of excellence through participatory leadership of all stakeholders at every level, the objectives of accreditation and quality assurance can be achieved. Good governance and institutional leadership can play a key role in ensuring quality in higher education. Regular workshops for faculty members are organised to update them about the recent trends in teaching, learning and other professional needs, reinforcing the culture of excellence. Senior leaders and educators who have taken part in national and international consultations on education are in a position to support the culture of excellence and are able to recognise developing societal requirements and respond to them through institutional interventions. Any programme must undergo a feasibility study before being implemented. Regular gatherings at various levels guarantee that the infrastructure and instructional resources are upgraded to handle the dynamically shifting educational environment. By including the faculty and students in a variety of activities, the institute fosters a culture of participative management. The management of facts, information and objectives serves as the basis for all institutional choices. It was permissible for both students and faculty to express whatever ideas they had for enhancing the institute’s excellence in any area. To ensure the smooth and organised operation of the institute, the principal, course coordinators and staff members are involved in defining the policies and procedures, framing guidelines and rules and regulations pertaining to admission, placement, discipline, grievance, counselling, training and development, and library services, among other things, and effectively implementing the same. As a result, the institution’s vision, mission and goals are in line with the aims of higher education in order to ensure the quality of higher education through accreditation. The governance of the institution is reflective of an effective participatory leadership. Decentralisation and participative management are employed by the institution. In addition to engaging with stakeholders, the institution develops its strategic planning. The institution keeps an eye open and assesses its plans and policies. The institution needs to be involved in developing leaders at all levels. The management of facts, information and objectives serves as the basis for all institutional choices. The accrediting criteria/standards clearly describe the fundamental requirements for faculty staff, workload, academic pursuits of professors and students, curriculum updates, learning outcomes, industrial ties, etc. Numerous policy guidelines are created and implemented for the academic and administrative operations of HEIs as a result of accreditation. However, there is a need for a common holistic excellence framework for HEIs because there are numerous accrediting bodies available at the institutional and programme levels, each with their own standards/criteria and hundreds of compliance formats. The need for numerous criteria and essential characteristics for establishing excellence in higher education institutions will be met by that one common model or framework that can be future focus of the research.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

Soumendra Kumar Patra  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2199-4297

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2199-4297

Leena P. Singh  https://orcid.org/0009-0000-8545-3903

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-8545-3903

Gola, M. M. (2003). Premises to accreditation: A minimum set of accreditation requirements. In Accreditation Models in Higher Education Experiences and Perspectives: ENQA Workshop Reports 3 (pp. 25–31). European Network for Quality Assurance in Higher Education, Helsinki.

National Assessment and Accreditation Council. (2013, June). Manual for self-study report: Affiliated/constituent colleges. http://dcedu.in/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/ssr_naac.pdf

UNESCO. (1998 October 5–8). Vision of the concepts of quality accreditation [Paper presentation]. The UNESCO World Conference of Higher Education (Paris, 1998) and follow-up meetings, GUNI Secretariat, Barcelona.