1 IMI Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

Today web-enabled services ranging from information sharing to online purchasing of products or services have become an increasingly frequent affair. In this context, previous research has explored the nature of complex cyber transactions and the various factors, which lead to formation of perceptions about such web-based services in the consumers’ minds. One important factor, which has been intriguing management researchers in this respect, is the influence of cultural values of consumers on online purchase intentions and perceptions about e-service quality. Most studies done in this context have used Hofstede’s national-level culture dimensions to do an individual-level analysis of consumer behaviour, but in doing so, have encountered a methodological issue known as ecological fallacy. This study wishes to demonstrate an alternate approach for culture-specific consumer purchase behaviour research using individual-level cultural values as study variables, thus eradicating the issue of ecological fallacy.

National culture, Online buying, ecological fallacy, e-service

Introduction

One of the most intriguing areas of contemporary research in consumer behaviour is the study of buying behaviour of consumers in an online environment (Jarvenpaa & Tractinsky, 1999; McKnight et al., 2002; Schlosser et al., 2006; Van der Heijden et al., 2003). The Internet provides a platform for low-cost, time-saving transactions between buyers and sellers across geographical borders, with more flexibility for shopping at convenient hours, and a greater variety to choose from (Jarvenpaa & Tractinsky, 1999). However, the online mode of business transactions is not free from its shortcomings. The greatest pitfall of online commercial transactions is the lack of trust in the consumers resulting in the reluctance of the consumers to make the actual transactions (Donthu & Yoo, 1998; Jarvenpaa & Tractinsky, 1999; Van der Heijden et al., 2003).

Studies have been conducted to develop models of e-purchase intentions and cause-effect relationships have been constructed to gain a comprehensive understanding of online purchase intentions (McKnight et al., 2002; Pavlou, 2003; Van der Heijden et al., 2003). Trust, perceived ease of use and usefulness of website design have been identified as the key influencing factors of online purchase intentions of consumers in these studies. The above dimensions have been backed by one of the most widely accepted theories in Information System (IS) literature—the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) theory which states that the acceptance of a new technology by an end user will depend on the perceived ease of use (user-friendliness) and perceived usefulness of the technology (Koufaris, 2002; Lai & Li, 2005; Loiacano et al., 2007).

In some studies, researchers have emphasised the role of national culture dimensions on the formation of attitudes towards e-commerce websites (Donthu & Yoo, 1998; Furrer, 2000; Pavlou, 2003). Research in this domain has shown a positive relation between national-level cultural values and the perceptions of a website’s quality (Donthu & Yoo, 1998; Furrer, 2000; Pavlou, 2003) in terms of perceptions of trust, ease of use and usefulness. The serious drawback of these studies is that the framework of choice for national culture used in all these studies has been unanimous—Hofstede’s (2001) dimensions of national culture (Donthu & Yoo, 1998; Furrer, 2000; Pavlou, 2003). However, in doing so, these studies have incurred a methodological error known as ecological fallacy—which occurs when indicators meant to represent constructs at a different level are used as proxies for different levels of analyses.

Hofstede’s (2001) framework of national culture is meant for national-level analyses, not individual-level analyses. However, several researchers have been found to use the Hofstede typology as a measure of individual-level cultural values (Donthu & Yoo, 1998; Huang & Crotts, 2019; Pavlou, 2003). This type of methodological error of measuring individual-level variables using national-level measures gives rise to a methodological shortcoming known as the ecological fallacy (Hofstede, 2001; Walker, 2021), giving an improper interpretation of the findings.

This study wished to rectify this potential mistake of the previous research models by constructing a modified model of online consumer buying behaviour by using the culture orientation framework as given by Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck which helps in measuring cultural values at an individual level (Maznevski et al., 2002; Steenkamp, 2019). Hypotheses have been proposed for empirical validation of the model.

Literature Review

Website Quality

One of the earliest attempts to develop a framework for measuring service quality was made by Parasuraman et al. (1988) through the development of the SERVQUAL model. Parasuraman et al. (1988) defined service quality as—the relative perceptual distance between customer expectations and evaluations of service experiences. In the context of internet-based services, Zeithaml et al. (2002) have defined e-service quality as the ‘extent to which a website facilitates efficient and effective shopping, purchasing and delivery’. Zeithaml et al. (2002) conducted focus groups to generate the items for e-service quality. They identified 11 dimensions of e-service quality: reliability, responsiveness, access, flexibility, ease of navigation, efficiency, assurance/trust, security/privacy, price knowledge, site aesthetics, and customisation/personalisation.

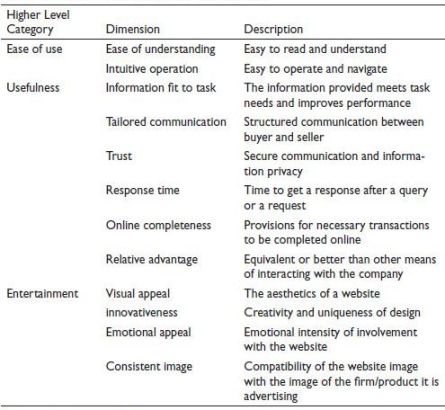

Yoo and Donthu (2001) developed the SITEQUAL, a nine-item, five-point Likert-type instrument to measure e-service quality. The SITEQUAL has four dimensions—ease of use, aesthetic design, processing speed and security. The issue with these early instruments was the lack of comprehensiveness and a shift in focus from websites to Internet. A full website-focused approach to e-service quality first came into picture with the framework proposed by Loiacano et al. (2007) which they termed WEBQUAL, in tribute to its offline counterpart—SERVQUAL. Loiacano et al. (2007) came up with 12 parameters of website quality, which they further clubbed into three broad classifications in their latest ramification of the WEBQUAL model—Ease of Use, Usefulness and Entertainment. Although the WEBQUAL model is more complex than some of the simpler models discussed above, such as SITEQUAL, the reason for choosing this model was the inclusion of all the potential dimensions of web quality making it a more comprehensive instrument for quantifying quality of a website. Another reason is that WEBQUAL is gaining rapid popularity among IS and marketing researchers as a valid instrument for measuring website design quality (Loiacano et al., 2007; Tsikriktis, 2002).

Website Quality and End User Purchase Intentions

McKnight et al. (2002) developed the trust-building model (TBM) of online consumer purchasing behaviour in a study with 1,729 students from three large universities in the USA to find that several antecedent factors of website design have a significant influence on the online trust factor of consumers. Perceptions of website quality were found to positively influence the trusting perceptions of vendors and willingness to depend on the vendors. This again had a significant influence on the intention of the consumers to buy from the site. Lee and Lin (2005) surveyed 297 online consumers to investigate the relationship between customer perceptions of e-service quality and purchase intentions. The results showed that the dimensions of website design- responsiveness, reliability and trust have a positive effect on customer satisfaction and consequently, intention to purchase.

In a study by Liu and Arnett (2000), information and service quality, system use, playfulness and system design factors of web quality were found to have significant effects on the purchase intentions of consumers. In an online platform, the consumers have to depend on the information provided by the websites to learn about the various products and services. The easier the site will allow the consumers to navigate through its contents, the more at ease the consumer will feel. According to TAM, this will create a favourable attitude towards the website.

Empirical research using the TAM framework has shown that usefulness and ease of use are two important aspects of web design, which the web developers have identified as significant determinants of web business success (Hamzah et al., 2022; Koufaris, 2002; Lai & Li, 2005). Shia et al. (2016) found a strong impact of website quality factors on customer satisfaction. In a similar vein, Napitupulu (2017) has also proven that website usability and level of service integration have significant and positive effects on users’ satisfaction.

Another aspect that consumers will look into while evaluating which site is good and which site is bad, is the perception of how useful and trustworthy the information is displayed on the site. If a site can project a strong sense of trust to the end users, consumers will be more trusting to do transactions through those sites. The proposition that perceived usefulness of a website will have a positive influence on the consumer’s perception of a website’s quality is backed by the Transaction Cost theory, which states that entities try to reduce costs associated with economic exchange by cutting down on their search costs associated with product and price discovery, negotiation costs and settlement costs. The internet can serve as a perfect medium for reducing transaction costs by reducing all the above costs mentioned. Empirical data also supports the fact that e-commerce has the potential to reduce transaction costs compared to traditional media of transaction (Lampe et al, 2007).

A third important design element for websites that has been identified by researchers is the entertainment/playfulness factor (Koufaris, 2002; Liu & Arnett, 2000; Loiacano et al., 2007). The entertainment aspect of a website lies in the graphics, the visual display, the appearance and the special features of a website (Gligor, 2015; Koufaris, 2002). The previous research has used the flow theory (Csikszentmihalyi, 1977, as cited in Koufaris, 2002) to justify their inclusion of entertainment factors in web design parameters (Loiacano et al., 2007). The flow theory suggests that human beings can sometimes experience a state of flow, which is a cognitive state of the mind where people have a sensation of being fully immersed in a task (Ozkara et al., 2017). When people are in a flow state, they ‘shift into a common mode of experience when they become absorbed in their activity’ (Csikszentmihalyi, 1977; as cited in Koufaris, 2002). The main effect of this flow state is a sharpening of awareness about the task so that unnecessary thoughts and preoccupations are replaced by ‘a loss of self-consciousness, by responsiveness to clear goals and unambiguous feedback, and by a sense of control over the environment’ (Csikszentmihalyi, 1977; as cited in Koufaris, 2002).

From the flow theory, it may be inferred that while designing websites for e-commerce purposes, web developers must keep in mind the salient features of a website, which can trigger a flow experience in the consumers. The empirical works done in this context support the logic proposed here (Bilgihan et al., 2014). In fact, the WEBQUAL instrument developed by Loiacano et al. (2007) captures all three important design elements of web quality—ease of use, usefulness and entertainment. The dimensions of website quality are described in Table 1.

Web-quality & National Culture: The Ecological Fallacy Issue

Culture may be defined as ‘the collective programming of the mind’ (Hofstede, 2001). The study of culture has its research origin in the works of anthropologists like Boas and Benedict (Sanday, 1977). The anthropological works of the early researchers have focused on culture-specific studies (Sanday, 1977) where the approach has been to spend time with the members of a society and then unveil the native’s point of view (Hill, 1993; Sanday, 1977). Culture researchers have developed several frameworks to capture the construct of national culture taking the Cultural Orientation Model as the basic starting point. Some of the most prominent models of culture are Schwartz’s model, Hall’s model, Trompenaars’ model, House et al’s GLOBE framework and the most well-known of them all—Hofstede’s typology of National Culture (Sent & Kroese, 2022).

Table 1. WEBQUAL Dimensions and Descriptions.

Source: Loiacano et al. (2007).

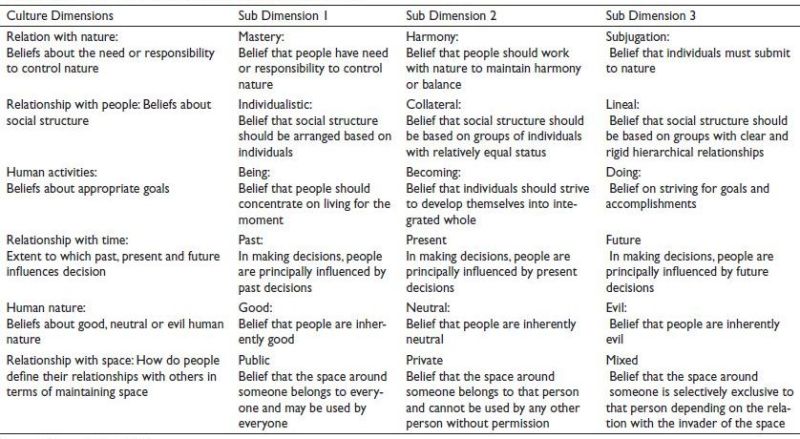

The earliest model of cultural values was given by Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck (1961, Maznevski et al., 2002) who came up with the Cultural Value Orientation Framework. Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck’s Value Orientation Model (Maznevski et al., 2002; Yan & Li, 2021) describes six individual cultural value dimensions, namely, relationship with nature, relationship with other people, human activities, relation with time, relationship with space and human nature (Kluckhohn & Strodtbeck, 1961). Each dimension has three continuums depending on the type of dimension.

At a much broader level of analysis, Hofstede (2001) conducted the IBM Value Survey and came up with five dimensions of culture at the national level – individualism/collectivism, power distance, masculinity/femininity, uncertainty avoidance and future goal orientation. His study has been, till to date, the most comprehensive work on national culture, and the most cited one in cross-cultural research (Donthu & Yoo, 1998; Jackson, 2020; Litvin, 2019).

However, Hofstede (2001) himself has cautioned the researchers that his measure of national culture is for a national-level comparison of cultural values and should not be used to measure its effect on individual-level perceptions. If such an attempt is made, it will cause the methodological error of ecological fallacy (Hofstede, 2001; Sajadi & Badreh, 2019). However, despite that, numerous studies have used the Hofstede typology to elucidate individual-level value perceptions (Bakir et al., 2020; Donthu & Yoo, 1998; Jarvenpaa & Tractinsky, 1999).

The ecological fallacy occurs, when, one variable in a study is measured at the individual level and another variable at the national level (Hofstede, 2001). The fallacy lies in the assumption that the national level culture dimensions are a representation of the individual level perceptions of cultural values (Triandis et al, 1995). Similar errors have been noticed in the works of Sigala and Sakellaridis (2004), and Dash et al. (2007), and criticised by Brewer and Venaik (2012). The problem with the use of Hofstede’s dimensions for individual-level analysis is that it leads to apples for oranges type of comparison.

However, the fact that they have all overlooked is that they have still used the instrument to measure individual-level perceptions of values. If Hofstede’s typology is to be used, the unit of analysis must be the nation, not individuals. Because of this conceptual error in the previous models of online consumer behaviour, we are proposing a refined model of online consumer purchase intention, by operationalising culture at the individual level of analysis using Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck’s framework (Maznevski et al., 2002). Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck’s framework (refer to Table 2) has a distinct advantage for individual-level analysis of value perceptions because it focuses on how individuals perceive that the world must operate and what do individuals perceive about the way that the world is really working.

Theoretical Framework & Research Propositions

The main relationship that this study wishes to investigate is how the cultural values of consumers influence their perceptions about the quality of web-based services and what impact such perceptions eventually have on their online purchase intention. Online consumer behaviour researchers have frequently explored the possibility of whether a cultural value system of individuals has any influence over the purchase intention of cyber consumers. The theoretical premise for such a conceptualisation is rooted in the signalling theory of communication and social identity theory of cognitive psychology.

Table 2. Kluckhohn & Strodtbeck’s Value Orientation Framework.

Source: Maznevski et al. (2002).

The signalling theory (Lampe et al., 2007) states that certain signals can have different interpretations for different individuals and the consequent variation in behaviour is a manifestation of the different opinions formed by the respondents about the meaning of the signal. From the signalling theory, it can be inferred that the users will judge the quality of the websites, based on what information/signal the website is communicating to the users. This evaluation of the signals may be affected by the cultural value orientation of the consumers (Donthu & Yoo, 1998; Furrer, 2000; Pavlou, 2003).

Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck’s value dimensions may have a significant impact on the linear relationship between perceptions of website quality and online purchase intentions. The theory of reasoned action (TRA) is used here to explain the logic behind the interrelationship between cultural values and perception of website quality (Fishbein, 1979). Fishbein’s TRA states that ‘individuals evaluate the consequences of a particular behaviour and then take actions in lieu of their evaluations’.

Another important factor which determines the degree of new technology adoption is the consumer’s time perspective—especially whether they are past-oriented or future-oriented. Taking cue from the theory of time perspective, it may be argued that human beings, who believe that the past was better than the present, will think that new technologies are eliminating the good traditional shopping experiences of the past (Settle et al., 1978). These individuals will be more unwilling to accept new technologies. Similarly, individuals with a present/future time orientation will realise the benefits of online transactions because they would want to be upgraded with time and are quick to realise the future opportunities that lay ahead (Blázquez, 2014). For such individuals, the present/future time-orientation cultural value is expected to have a strong moderating effect on the web quality-purchase intention relation. Therefore, there is strong reason to believe that time orientation (past/future) may have a moderating effect on the relationship between ease of use and usefulness dimensions of web quality and purchase intention.

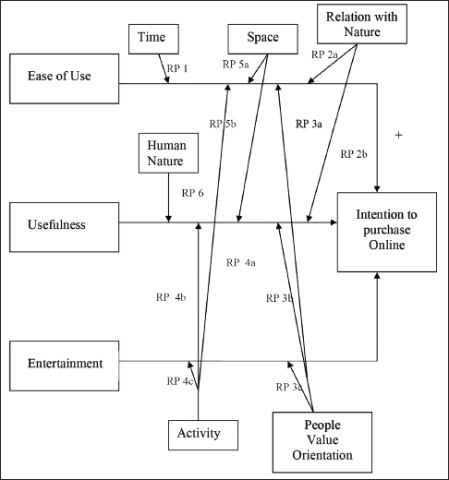

Research Proposition 1: The relationship between perceived usefulness of website and online purchase intention will be moderated by the time orientation cultural value of consumers.

The relationship with nature dimension of the Cultural Orientation Model is about the belief in individuals that they are the masters of the external environment and vice versa (Gaur et al., 2019). This belief may have a strong influence on the perceptions of ease use and usability categories of WEBQUAL and the consequent impact on online purchase behaviour. The more an individual values autonomy and accepts freedom of action for granted, more would be his demand for improved ease of use and usefulness of websites. Similarly, for individuals who believe in harmony/subjugation with the external environment, there will be little urge for such quality improvement. They are ready to compromise and adjust to the website ambiguities if needed (Kim & Choi, 2005). Hence for them, ease of use and usefulness of websites will be perceived more leniently, with little demand for modifications. Hence, it is proposed that-

Research Proposition 2a: The relationship between perceived ease of use dimension of WEBQUAL and consumer’s online purchase intention will be moderated by the relationship with nature orientation of consumers.

Research Proposition 2b: The relationship between perceived usefulness dimension of WEBQUAL and consumer’s online purchase intention will be moderated by the relationship with nature orientation of consumers.

The consumers with individualistic values will differ from those with collateral/lineal values in their perceptions of web quality. As per Hofstede’s Individualism/collectivism spectrum, individualists will have more need for unique features and complementary services because they will want to have customised web pages so that they have to depend less on others to achieve their goals (Miao et al., 2020). They would assess the quality of a website based on how unique it is so that individual experiences need not be a common one. For individualists, personal pleasure is also an important factor in judging a website’s quality. Similarly, the collectivists will judge the quality of a website based on the ease-of-use dimensions of WEBQUAL because they want to have more people to interact at the same level of ease and to experience enjoyment with an appeal for a large base of users (Costa Pacheco et al., 2021). Based on the above logic, it is proposed that -

Research Proposition 3a: The relationship between perceived usefulness of WEBQUAL and online purchase intention will be moderated by the relationship with people value orientation of consumers.

Research Proposition 3b: The relationship between perceived ease of use dimension of WEBQUAL and online purchase intention will be moderated by the people value orientation of consumers.

Research Proposition 3c: The relationship between perceived entertainment dimension of WEBQUAL and online purchase intention will be moderated by the people value orientation of consumers.

The belief about human activities—being, becoming and doing, can also have far-reaching effects on the rating of consumers about website quality. Those with the ‘being’ value orientation will have less reason to improvement of website quality because they are content with the present state of web quality. Accordingly, the ‘being’ value orientation should have no significant impact on the relationship between overall perceived web quality and intention to purchase (Simcox, 2019).

But those with ‘becoming’ and ‘doing’ values will always want to have greater ease of use, usefulness, and entertainment from the web designs as such individuals always try to strive for improvement in their life (Franco & Meneses, 2020; Maznevski et al., 2002). Therefore, it is proposed that

Research Proposition 4a: The relationship between perceived ease of use dimension of WEBQUAL and online purchase intention will be moderated by the activity orientation of individuals.

Research Proposition 4b: The relationship between perceived usefulness of WEBQUAL and online purchase intention will be moderated by the activity orientation of individuals

Research Proposition 4c: The relationship between perceived entertainment dimension of WEBQUAL and online purchase intention will be moderated by the activity orientation of individuals

Values of personal space can also have a significant influence on consumer behaviour (Luck & Benkenstein, 2015). The consumers who value private space would want more security about their information will be less trusting about the websites and will want to have information according to their specific requirements. For consumers who believe in public/mixed space, the usefulness dimension is of less concern, and the greater concern is for the ease-of-use dimension. Accordingly, it is proposed that

Research Proposition 5a: The relationship between perceived usefulness and online purchase intention will be moderated by the value orientation about space.

Research Proposition 5b: The relationship between perceived ease of use and online purchase intention will be moderated by the value orientation about space.

Regarding the value dimension about nature of human beings, those who believe that people are necessarily good will have more positive perceptions about the trust dimension of perceived web quality, while those who believe that people are necessarily evil or a mixture of both, for them trust and security issues will be of more concern (Webster et al., 2021). Therefore, usability will be of major concern for people with a value that human beings cannot be trusted to be good all the time.

Research Proposition 6: The relationship between the usefulness dimension of WEBQUAL and online purchase intention will be positively moderated by the value about nature of human beings.

The research questions are represented in a research framework (refer to Figure 1).

Measurement of Variables

Standard indices exist for measuring each of the above constructs. Perceived ease of use, usefulness and entertainment aspects of websites may be measured using the 24-item WEBQUAL scale developed by Loiacano et al. (2002). Each sub-dimension of the WEBQUAL scale has been validated and replicated in several studies (Barnes & Vidgen, 2002; Tsikriktis, 2002). Alternatively, researchers may use the SITEQUAL scale developed by Yoo and Donthu (2001) which is a 9-item Likert scale capturing four dimensions- ease of use, aesthetic design, processing speed and security. Cultural values at the individual level may be measured using the cultural perspectives questionnaire version 4 (CPQ 4) developed by Maznevski et al. (2002) which is a 79 item 7-point Likert scale that captures four of the six dimensions of Kluchhohn and Strodtbeck—relationship with nature, relation with people, activity orientation and belief about human nature.

The constructs of space and time were not included in this scale, though we have shown through our theoretical framework how these two dimensions can influence the perceptions of website quality and consequently the online purchase intentions of consumers. Hence, we propose to integrate the two unused dimensions of space and time in our final questionnaire which will help us address all the major individual-level cultural value dimensions in an e-commerce context. As for our dependent variable, online purchase intention can be measured using the single-item scale used by Koufaris (2002) or the 3-item scale developed by Lai and Li (2005) to measure intention to use internet banking.

Figure 1. Proposed Theoretical Model of Culture Moderated Consumer Purchase Intention.

Discussions and Directions for Future Research

We hope that the framework proposed in this study may help researchers in resolving the dilemma associated with investigating the impact of cultural values on consumer online buying behaviours using within-country data instead of cross-country data. By using the cultural value framework, researchers and marketing analysts may be better able to get rid of the ecological fallacy error in understanding the different cultural value orientations existing at an individual level and consequently develop more innovative e-commerce applications which can help in incorporating such modifications on a generalised basis (Walker, 2021).

The above framework may be extended for different e-commerce platforms such as online B-2-C transactions, internet banking and e-business websites such as e Bay and Amazon. The framework may also be extended to traditional consumer behaviour studies such as influence of consumer’s cultural values on their attitude towards advertisements and promotions. More studies are required to increase the validity of the scales used to measure individual-level cultural values (Maznevski et al., 2002).

Although the above framework may seem to be slightly complicated to apply in real practice, we expect that with proper orientation towards the cultural value orientation of the target population, e-commerce businesses will be able to incorporate different cultural value cues in the design of e-commerce web pages to help improve perceived quality of the same in the minds of the users/online consumers. We suggest that such user-centric website designs will result in more favourable intentions to buy from online e-commerce transaction points by consumers. In the domain of e-commerce research, simplified models using one or two dimensions of cultural values may be used to understand specific relationships with different variables of interest such as online social networking, net banking, consumer attitude towards online advertisements and online gaming.

To illustrate further, an e-commerce-based organisation dealing in online share trading, may wish to make its customers more trusting about investing their funds with their organisations. For such organisations, the trust factor of perceived usefulness dimension of website quality will be the prime factor of concern. Such organisations can then try to understand which cultural values were dominant among their customers by conducting a survey with a reasonable sample of the customer base with the subscales of CPQ and the WEBQUAL questionnaires to find how a majority of the users felt regarding their own beliefs about privacy and trust on others and how they felt about their privacy and security while interacting with the website (De Mooij & Hofstede, 2011). Based on such findings, the management can instruct the web developers involved in designing the web pages to incorporate trust-specific messages and cultural cues to increase perceived trustfulness of the websites.

Similarly, website quality of an organisation focused on entertainment business such as online gaming, audio/video hosting, blogging or social networking will depend on all the WEBQUAL dimensions of perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness and aesthetics, as well as several dimensions of cultural values such as relationship with nature, values about activity, values about time and space and so on. In future, there is a scope for incorporating other individual-level variables such as personality, locus of control and socio-demographic variables such as computer literacy, gender and age in the above model to reach a deeper level of exhaustiveness in the proposed framework. As a logical next step, we urge fellow researchers in cross-cultural e-commerce research to further validate our model in different cultural contexts.

We have earlier mentioned that the CPQ 4 scale (Maznevski et al., 2002) needs to be extended further to include the time and space dimensions of culture. Therefore, future research should be devoted to upgrading the CPQ 4 scale- which will help us to measure all the major dimensions of individual cultural differences (Napitupulu, 2017). On a related note, it may also be argued, that given the case of cultural relativism (Hofstede, 2001), more exploration is needed to get a more enriching understanding of the latent values embedded in native cultures. Hence, future studies should consider investigating cultural values from an exploratory perspective to add new insights to the seminal Kluchhohn and Strodtbeck (1961) cultural framework.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Pratyush Banerjee  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5415-2139

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5415-2139

Bakir, A., Gentina, E., & de Araújo Gil, L. (2020). What shapes adolescents’ attitudes toward luxury brands? The role of self-worth, self-construal, gender and national culture. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 57, 102208.

Barnes, S., & Vidgen, R. (2002). An Integrative approach to the assessment of e-commerce quality. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 3 (3), 114–127.

Bilgihan, A., Okumus, F., Nusair, K., & Bujisic, M. (2014). Online experiences: Flow theory, measuring online customer experience in e-commerce and managerial implications for the lodging industry. Information Technology & Tourism, 14(1), 49–71.

Blázquez, M. (2014) Fashion shopping in multichannel retail: the role of technology in enhancing the customer experience. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 18(4), 97–116.

Brewer, P., & Venaik, S. (2012). On the misuse of national culture dimensions. International Marketing Review, 29 (6), 673–683.

Costa Pacheco, D., Moniz, D. D. S. A., Isabel, A., Nunes Caldeira, S., & Dias Lopes Silva, O. (2021). Online impulse buying–integrative review of social factors and marketing stimuli. In International Conference on Advanced Research in Technologies, Information, Innovation and Sustainability (pp. 629–640). Springer, Cham.

Dash, S., Burning, E., & Guin, K. K. (2007). Antecedents of long-term buyer-seller relationships: A cross cultural integration. Academy of Marketing Science Review, 1, 1–24.

De Mooij, M., & Hofstede, G. (2011). Cross-cultural consumer behavior: A review of research findings. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 23(3–4), 181–192.

Donthu, N., & Yoo, B. (1998). Cultural influence on service quality expectations. Journal of Service Research, 1(2), 178–186.

Fishbein, M. (1979). A theory of reasoned action: Some applications and implications. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 27, 65–116.

Franco, M., & Meneses, R. (2020). The influence of culture in customers’ expectations about the hotel service in Latin countries with different human development levels. European Journal of Tourism, Hospitality and Recreation, 10(1), 56–73.

Gaur, J., Mani, V., Banerjee, P., Amini, M., & Gupta, R. (2019). Towards building circular economy: A cross-cultural study of consumers’ purchase intentions for reconstructed products. Management Decision, 57(4), 886–903.

Gligor, D. M. (2015). Identifying the dimensions of logistics service quality in an online B2C context. Journal of Transportation Management, 26(1), 6.

Hamzah, M. L., Rahmadhani, R. F., & Purwati, A. A. (2022). An integration of Webqual 4.0, importance performance analysis and customer satisfaction index on e-campus. Journal of System and Management Sciences, 12(3), 25–50.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Huang, S. S., & Crotts, J. (2019). Relationships between Hofstede's cultural dimensions and tourist satisfaction: A cross-country cross-sample examination. Tourism Management, 72, 232–241.

Jackson, T. (2020). The legacy of Geert Hofstede. International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management, 20(1), 3–6.

Jarvenpaa, S. L., & Tractinsky, N. (1999). Consumer trust in an internet store: A cross- cultural validation. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 5(2), 1–36.

Koufaris, M. (2002). Applying the technology acceptance model and flow theory to online consumer behavior. Information Systems Research, 13(2), 205–223.

Kluckhohn, F. R., & Strodtbeck, F. L. (1961). Variations in value orientations. Row, Peterson.

Lai, V. S., & Li, H. (2005). Technology acceptance model for internet banking: An invariance analysis. Information & Management, 42, 373–386.

Loiacano, E. T., Chen, D. Q., & Goodhue, D. L. (2002). WebQual revisited: predicting the intent to reuse a website. Paper presented at the 8th Americas Conference on Information Systems.

Loiacono, E. T., Watson, R. T., & Goodhue, D. L. (2007). WebQual: An instrument for consumer evaluation of web sites. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 51-87.

Lee, G. G., & Lin, H. F. (2005). Customer perceptions of e-service quality in online shopping. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 33(2), 161–176.

Liu, C., & Arnett, K. P. (2000). Exploring the factors associated with Web site success in the context of electronic commerce. Information & Management, 38, 23–33.

Maznevski, M. L., Gomez, C. B., DiStefano, J. J., Noordervahen, N. G., & Wu, P. C. (2002). Cultural dimensions at the individual level of analysis: The cultural orientations framework. International Journal of Cross-cultural Management, 2(3), 275–295.

McKnight, D. H., Chaudhary, V., & Kacmar, C. (2002). The impact of initial consumer trust on intentions to transact with a web site: A trust building model. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 11, 297–323.

Miao, M., Jalees, T., Qabool, S., & Zaman, S.I. (2020). The effects of personality, culture and store stimuli on impulsive buying behavior: Evidence from emerging market of Pakistan. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 32(1), 188–204.

Napitupulu, D. (2017). Analysis of factors affecting the website quality based on WebQual approach (study case: XYZ University). International Journal on Advanced Science Engineering Information Technology, 7(3), 792–798.

Pavlou, P. A. (2003). Consumer acceptance of electronic commerce: Integrating trust and risk with the technology acceptance model. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 7(3), 69–103.

Schlosser, A. E., White, T. B., & Lloyd, S. M. (2006). Converting web site visitors into buyers: How web site investment increases consumer trusting beliefs and online purchase intentions. Journal of Marketing, 70, 133–148.

Shia, B. C., Chen, M., & Ramdansyah, A. D. (2016). Measuring customer satisfaction toward localization website by WebQual and importance performance analysis (case study on AliexPress Site in Indonesia). American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 6(2), 117.

Sigala, M., & Sakellaridis, O. (2004). Web user’s cultural profiles and e service quality: Internalization implications for tourism websites. Information Technology & Tourism, 7, 13–22.

Simcox, D. E. (2019). Cultural foundations for leisure preference, behavior, and environmental orientation. In Culture, conflict, and communication in the wildland-urban interface (pp. 267–280). Routledge.

Steenkamp, J. B. E. (2019). Global versus local consumer culture: Theory, measurement, and future research directions. Journal of International Marketing, 27(1), 1–19.

Tsikriktis, N. (2002). Does culture influence web site quality expectations? An empirical study. Journal of Service Research, 5(2), 101–112.

Van der Heijden, H., Verhagen, T., & Creemers, M. (2003). Understanding online purchase intentions: Contributions from technology and trust perspectives. European Journal of Information Systems, 12, 41–48.

Walker, J. T. (2021). Ecological fallacy. The Encyclopedia of Research Methods in Criminology and Criminal Justice, 2, 478–482.

Webster, R. J., Morrone, N., & Saucier, D. A. (2021). The effects of belief in pure good and belief in pure evil on consumer ethics. Personality and Individual Differences, 177, 110768.

Yan, J., & Li, Y. (2021). Comparative study of cultural value orientation between China and America. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 11(1), 97–105.

Yoo, B., & Donthu, N. (2001). Developing a scale to measure the perceived quality of an internet shopping site (SITEQUAL). Quarterly Journal of Electronic Commerce, 2(1), 31–47.

Zeithaml, V. A., Parasuraman, A., & Malhotra, A. (2002). Service quality delivery through web sites: a critical review of extant knowledge. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 30(4), 358–371.