1GITAM School of Business, GITAM University Bengaluru, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

The importance of fostering entrepreneurship is inevitable in poverty alleviation programmes because it is the best way to create capabilities. Nurturing women entrepreneurship in a competent outfit will be a way to fight poverty. Schumpeter’s and Kirzner’s economic models of entrepreneurship show how women’s entrepreneurship should be identified, recruited, mentored and encouraged. So, the notion of eradicating poverty through profit in rural India can be by women entrepreneurs taking up radical and incremental innovation and achieving profitability, self-fulfilments and thus the positive economic outcome. Small and medium enterprises (SMEs), which are vehicles in which women entrepreneurship thrives, are very conducive for rural women. The unique qualities and skills which women entrepreneurs introduce into SMEs constitute a real potential source of innovation for economies. To Schumpeter, while the identification and exploitation of this source of opportunities involve radical innovations, Kirzner’s incremental innovations are brought to market and exploited by alert entrepreneurs.

Schumpeter’s and Kirzner’s economic models of entrepreneurship, innovation, SME, rural women

Introduction

The socio-economic and caste survey of 2011 shows the extent and depth of deprivations of rural India. Around 73.4% of families of the whole country are residing in rural areas. Despite the years of planning and unplanned execution of these plans, even the chances of modern employment reaching these families in near future are also a question, as only 3% of these families have at least one graduate. Poverty alleviation programmes and their incapability in creating capabilities for deprived sections are evident in this. Structural disparities are very crucial and severe in this context. The importance of fostering entrepreneurship is inevitable here because it is the best way to create capabilities. The question of why women’s entrepreneurship should be promoted can be answered by some realities. Women represent a higher share of the world’s poor due to unequal access to economic opportunities in both developed and developing countries (Boudet et al., 2018; Lefton, 2013). Improving the access of women to education and health care as well as economic opportunities can have significant positive outcomes for poverty reduction. Effective anti-poverty strategies need to consider the role of social institutions and culture, particularly in limiting the access of women to employment, inheritance and finance. So nurturing women entrepreneurship in a competent outfit will be a way to fight poverty. Schumpeter’s and Kirzner’s economic models of entrepreneurship show how women’s entrepreneurship should be identified, recruited, mentored and encouraged. So, the notion of eradicating poverty through profit generation in rural India can be through women entrepreneurs taking up radical and incremental innovation and achieving profitability, self-fulfilments and positive economic outcome.

Context

Women Entrepreneurship: Motivations to Potential

Different perceptions of entrepreneurship have been identified by economists throughout the evolution of the subject. Knight (1921) believed that entrepreneurs face uncertainty from the unknown; Alfred Marshall saw an entrepreneur as leader and manager (Karayiannis, 2009); JB Say recognised the entrepreneur as a manager because they play an important role in coordinating the factors of production and distribution (Koolman, 1971). However, most of these economic theories recognise the fact that entrepreneurship contributes significantly to the development of the economy. Schumpeter (1994) argued that the entrepreneur is the one who brings the innovations that create real development in the economy, meaning that without the entrepreneur economic growth will be very slow. Yet despite their centrality, little is known about entrepreneurs: what motivates them, how they emerge, why they succeed. The existing literature on women entrepreneurs is limited, especially regarding their distinct characteristics and motivations (Cohoon et al., 2010). Small and medium enterprises (SMEs), which are vehicles of development in which entrepreneurship thrives, play a key role in triggering and sustaining economic growth and equitable development in developing countries. The exploitation of the potential in the indigenous sectors as an engine for growth, using local resources and appropriate technology which is the nature of SMEs, is seen as an alternative development model to the traditional large-scale intensive ‘stages of growth’ paradigm in developing economies. In exploring why women entrepreneurs’ activities are mostly SME-based, most studies argued that the nature of SMEs is very conducive for women (Kalyani & Kumar, 2011; Singh & Raina, 2013). Women want businesses that they can combine with family life by looking after their children and their household and earning some income at the same time (Sharma, 2013). The unique qualities and skills which women entrepreneurs introduce into SMEs constitute a real potential source of innovation for economies. This article follows a descriptive analysis approach that explains the theoretical underpinning to evolve the framework for entrepreneurship development among Indian women. The rest of the article includes a discussion on the ideas of Joseph Schumpeter and Israel Meir Kirzner followed by implications on women entrepreneurship in India. The final section concludes the discussion with policy perspectives on an end outcome basis.

Discussions

The Economic Perspective of Entrepreneurship: Schumpeter Version

Joseph Schumpeter is the economist who has most prominently drawn attention to the innovating entrepreneur. His major contributions to the theory of entrepreneurship are included in his book The Theory of Economic Development (Schumpeter, 1911) first published in 1911. Schumpeter argued that innovation meant doing more with the same number of resources available to anyone. Schumpeter believed entrepreneurship not only meant management of a firm but, more importantly, the leadership of the firm, in contrast to the many imitators who follow the innovative leader of the entrepreneurs. The entrepreneur is therefore responsible for the continuous improvement of the economic system. According to Schumpeter, the economy does not grow like a tree, ‘steadily and continuously’, but through an individual’s creative or innovative responses to opportunities. By necessity or by desire, entrepreneurs create qualitatively new phenomena (Schumpeter & Swedberg, 2014), which is what makes the economy grow. Hence, the primary consequence of Schumpeter’s entrepreneurship is the long-running economic development of the capitalist system, and the entrepreneur is the innovator in economic life. Notably, Schumpeterian entrepreneurs are principally regarded to own and direct small independent firms that are innovative and creative.

The Economic Perspective of Entrepreneurship: Kirzner’s Version

Israel Meir Kirzner highlighted and summarised the Austrians’ (Mises and Hayek) economic views of entrepreneurship in his book Competition and Entrepreneurship (Kirzner, 1973). Kirzner focused on the alertness for profit opportunities as the key to understanding entrepreneurship. According to Hayek and Kirzner, knowledge is unevenly distributed in and among individuals, with the consequence that the market uses resources imperfectly (Ebner, 2005). This mismatch in knowledge and information and gaps that others have not yet perceived and exploited in the market process translate into profit opportunities for those individuals with particular, unique knowledge of market discrepancies. The entrepreneurial role is that of discovering or alertly noticing where discrepancies have occurred in the market process, and of moving to take advantage of such discoveries. According to Kirzner, entrepreneurs are the persons in the economy who are alert to discover and exploit these profit opportunities. The emphasis is thus on the entrepreneurs being the equilibrating forces in the market process by simply noticing profitable opportunities arising from unanticipated, independently caused changes in underlying market circumstances. Another equally important feature of Kirzner’s view is that the entrepreneur is a visionary, and possesses entrepreneurial or psychological qualities of boldness, determination, innovation and self-confidence (Kirzner, 1973).

Schumpeter’s and Kirzner’s Economic Models of Entrepreneurship for Indian Women

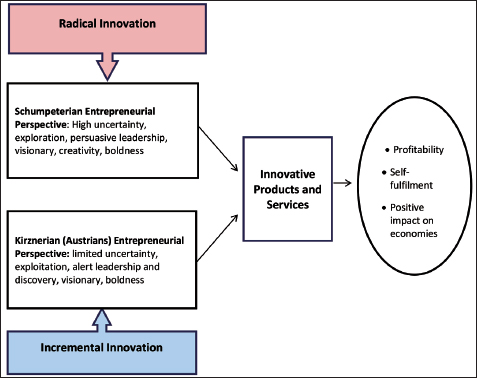

Schumpeter and Kirzner share different aspects of the role of the entrepreneur relevant to our notion. The gap between Schumpeter’s and Kirzner’s views is real and complementary. The two views have explicitly emphasised two distinct and complementary types of identification and exploitation of sources of opportunities in their theories, which is vital in the entrepreneurial process. To Schumpeter, while the identification and exploitation of these sources of opportunities may involve radical innovations, Kirzner’s incremental innovations are brought to the market and exploited by alert entrepreneurs. These two means of business ventures create a major component of the entrepreneurial process which will help to understand how women enter self-employment and the types of entrepreneurial activities they should aspire to (Figure 1).

The endurance of women entrepreneurs will be appreciated only if the product or service they launch generates profits, financially empowers them and has a positive impact on the economy. Innovation is the key factor that is proposed by this study, which helps achieve all these three outcomes. Both propositions of innovations explain the characteristics that are presumed to be part of successful innovative entrepreneurs. The women entrepreneurs can create an impactful presence in the market if they can utilise the market discrepancies as Kirzner emphasised (Incremental Innovation) and they should be equipped to launch their innovations as Schumpeter envisaged (Radical Innovation) (Figure 1).

Traditionally, we consider two sets of factors that motivate women entrepreneurship: push factors which include economic necessity, lack of childcare facilities, unacceptable working conditions, rigid hours, the wage gap between women and men, occupational segregation; positive factors pulling women into entrepreneurship include market opportunity, ambition, experience, an interest in a particular area of activity, social objectives, contacts, a need for flexible hours, greater income and financial independence, a desire for autonomy, personal growth and increased job satisfaction (Cavada et al., 2017; Muthuraman & Al-Haziazi, 2018; Solesvik et al., 2019). In India, women are at an economic disadvantage compared with men in terms of workforce participation and business ownership (WDI, 2021). Societal norms still discount women as the primary breadwinners in the family. Personal motivations such as the desire for autonomy, to control one’s destiny and the need to be personally fulfilled are not evenly nurtured in India due to patriarchal constraints (Geetha & Rajani, 2017; Premalatha, 2010). But the working of many self-help groups (SHGs) and their entrepreneurial ventures have substantially proved that entrepreneurship has provided an opportunity for women to discover a newfound sense of accomplishment in supporting themselves instead of relying on men and government welfare systems.

Figure 1. Implications of Schumpeterian and Kirznerian Perspectives on Women Entrepreneurship.

In rural India women, entrepreneurs are concentrated in traditional businesses such as food processing, hospitality and catering (Srivastava & Srivastava, 2010). The keywords such as innovation and alertness have not been given importance here or it is neglected. The current working of SHGs also revolves around the traditional options. Attempts of Kudumbasree and Self Employed Women’s Association also give that their entrepreneurial ventures are limited to traditional workers such as housekeeping, food processing to embroidery, bidi and agarbathis. So traditional activities as SMEs are the common orientation of Indian women where innovation and alertness are neglected. Creativity and explorations with high uncertainty that evolve from innovation are not cultivated in rural India. Despite growth in literacy rate, entrepreneurship training and scientific education are lacking in rural India.

The concentration on small-scale industries (SSI) limits them from radical innovation to an extent, despite the traditional constraints faced by SSI. The idea of innovation should be encouraged in the sense, which can create real growth potential. That may be a new product, a new method of production, the opening of a new market and capture of a new source of supply. But this never happened on large scale in rural India. Government’s negligence towards this is evident from the working of the newly sponsored Bharathiya Mahila Bank, which is to support the banking needs of women who want to become entrepreneurs. It has also signed pacts with beauty salons such as Naturals and Cavin Kare’s trends in Vogue. The bank offers loans for women in the range of ₹50,000 to ₹5 lakh to open day-care centres. It also gives loans starting from ₹5,000 for catering services. Here, on one side banks escape from dealing high uncertainty from innovation, secondly channelising their efforts to the hands of big players.

In Kirzner’s model, alertness and a better understanding of market matters, and entrepreneurial activities build in rural India for women are always without considering this aspect. The problem faced by SSI in general and women entrepreneurs specifically is always the problem of satisfying the market. The problem starts from when they limit their orientation to their local market. Even in the domestic market, lack of alertness results in no gap for them to utilise. So, lack of alertness in a globalised Indian market plus lack of innovation to create own market, shrinks the prospects of women entrepreneurs in rural India.

Conclusion and Policy Perspectives

The discussion on the notion of women entrepreneurship in the knowledge era in this study highlights how important are innovation and alertness, explained under two distinct perspectives. The access to knowledge enables them to design, deploy and use radical innovation, while incremental innovation helps them discover the need of the era. Kudumbasree mission in the state of Kerala in India gave an example in this context. The mission has assignments taken under information technology and information technology-enabled services which helped rural educated women to embrace the service sector growth in the country (Siwal, 2009). Much of the data entry work taken up by Government departments are being outsourced to Kudumbasree units which gave employment to over 2,500 poor women. In 2009–2010, the IT units were taken up mostly with digitising the below poverty line data and ration cards for the State Government Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana, Aam Aadmi Bima Yojana related works.

To conclude, investing in women and girls—in their education, health and access to assets and jobs—will have a multiplier effect on productivity, efficiency and sustained economic growth in developing countries. Here, what is needed is to at least ensure them elementary education which can stimulate innovation in their mind, which should be channelised, and enable them with different sets of competencies. Following Lawal et al. (2018), Tehseen et al. (2020) and Umar et al. (2018), the competencies that are critical for rural women entrepreneurs in the Indian context are:

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Mohammed Shameem  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4378-0652

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4378-0652

Boudet, A. M. M., Buitrago P., de la Briere, B.L., Newhouse, D., Matulevich, E.R., Scott, K., & Suarez-Becerra, P. (2018). Gender differences in poverty and household composition through the life-cycle: A global perspective. World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-8360

Cavada, M., Bobek, V., & Ma?ek, A. (2017). Motivation factors for female entrepreneurship in Mexico. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 5, 133–148. https://doi.org/10.15678/EBER.2017.050307

Cohoon, J. M., Wadhwa, V., & Mitchell, L. (2010). Are successful women entrepreneurs different from men? [SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 1604653]. Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1604653

Ebner, A. (2005). Hayek on entrepreneurship: Competition, market process, and cultural evolution. In J. Backhaus J. (Ed.), Entrepreneurship, money and coordination

(p. 3672). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781845427955.00010

Geetha, K., & Rajani, D. N. (2017). Factors motivating women to become entrepreneurs in Chittoor district. International Journal of Home Science, 3(2), 752–755.

Kalyani, P. R. B., & Kumar, D. (2011). Motivational factors, entrepreneurship and education: Study with reference to women in SMEs. Far East Journal of Psychology and Business, 3(3), 14–35.

Karayiannis, A. D. (2009). The Marshallian entrepreneur. History of Economic Ideas, 17(3), 75–102.

Kirzner, I. (1973). Competition and entrepreneurship (1st ed.). The University of Chicago Press. https://www.sjsu.edu/people/john.estill/courses/158-s15/Israel%20Kirzner%20-%20Competition%20And%20Entrepreneurship.pdf

Knight, F. H. (1921). Risk, uncertainty and profit [SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 1496192]. Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1496192

Koolman, G. (1971). Say’s conception of the role of the entrepreneur. Economica, 38(151), 269–286. https://doi.org/10.2307/2552843

Lawal, F., Iyiola, O., Adegbuyi, O., Ogunnaike, O., & Taiwo, A. A. (2018). Modelling the relationship between entrepreneurial climate and venture performance: The moderating role of entrepreneurial competencies. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Modelling-the-Relationship-between-Entrepreneurial-Lawal-Iyiola/bd605a92e0518492d667ce32f1b07e9a98b9d1b4

Lefton, R. (2013). Gender equality and women’s empowerment are key to addressing global poverty. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/gender-equality-and-womens-empowerment-are-key-to-addressing-global-poverty/

Muthuraman, S., & Al-Haziazi, M. (2018). Pull & push Motives for women entrepreneurs in Sultanate of Oman. ZENITH International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, 8(7), 79–95.

Premalatha, U. (2010). An empirical study on the impact of training and development on women entrepreneurs in Karnataka. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1706618

Schumpeter, J. A. (1911). The theory of economic development (1st ed.). Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/The-Theory-of-Economic-Development/Schumpeter/p/book/9780367705268

Schumpeter, J. A. (1994). History of economic analysis. Routledge.

Schumpeter, J. A., & Swedberg, R. (2014). Capitalism, socialism, and democracy. Routledge.

Sharma, Y. (2013). Women entrepreneur in India. IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 15(3), 09–14. https://doi.org/10.9790/487X-1530914

Singh, D. A., & Raina, M. (2013). Women entrepreneurs in micro, small and medium enterprises. International Journal of Management and Social Sciences Research, 2(8), 6.

Siwal, B. R. (2009). Gender framework analysis of empowerment of women: A case study of Kudumbashree programme [SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 1334478]. Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1334478

Solesvik, M., Iakovleva, T., & Trifilova, A. (2019). Motivation of female entrepreneurs: A cross-national study. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 26(5), 684–705. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-10-2018-0306

Srivastava, N., & Srivastava, R. (2010). Women, work, and employment outcomes in rural India. Economic & Political Weekly, 45(28), 49–63.

Tehseen, S., Qureshi, Z., Johara, F., & Ramayah, T. (2020). Assessing dimensions of entrepreneurial competencies: A type II (reflective-formative) measurement approach using PLS-SEM. Journal of Sustainability Science and Management, 15(2), 108–145.

Umar, A., Omar, C. M. Z. C., Hamzah, M. S. G., & Hashim, A. (2018). The mediating effect of innovation on entrepreneurial competencies and business success in Malaysian SMEs. International Business Research, 11(8), 142–153.

WDI. (2021). India | Data. World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/country/IN