1 Department of Entrepreneurship Education, Entrepreneurship Development Institute of India, Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India

2 Entrepreneurship Development Institute of India, Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

This simulation exercise offers transformative experiential learning in entrepreneurship. Integrated with the knowledge, skills and attitudes framework, this exercise immerses students in real-world scenarios of local livelihood businesses. Through hands-on engagement, students propose solutions, fostering critical thinking and problem-solving aligned with Bloom’s Taxonomy. The exercise yields profound experiential learning outcomes, empowering students with insights, skills and attitudes vital for entrepreneurial success.

Experiential learning, entrepreneurship education, KSA model, livelihood business, simulation exercise

Introduction

The strategic steps taken to reduce extreme poverty worldwide have opened up opportunities for entrepreneurial solutions to various social challenges, bridging the gap between developed markets and bottom-of-the-pyramid segments (Prahalad, 2019). Entrepreneurship at the bottom of the pyramid focuses on creating sustainable livelihood opportunities for individuals in low-income segments (Dhiman & Arora, 2024; Senapati & Parida, 2024; Sharma et al., 2023). Although these livelihood businesses operate in local markets and earn income daily, elements of entrepreneurship such as risk-taking, capital sourcing, management and resource gathering are still prevalent. Empowering these businesses with better tools, resources, and training is essential for generating income and improving their quality of life. This approach not only fosters economic independence but also drives social change by addressing issues such as poverty, unemployment, and inequality.

The term ‘bottom of the pyramid’, also known as the ‘base of the pyramid’ refers to the largest and poorest socio-economic group in the economic chain, a concept popularised by Prahalad and Hart (2004). This group typically includes people who live on less than a few dollars a day, making up the largest portion of the global population but commanding a small share of global income and resources (UNDP, 2014). Most of these individuals are involved in some form of income generation, either by working for someone or through livelihood businesses.

A recent report by the World Poverty Clock (2024) shows that in India, more than 30 crore people live below the extreme poverty line, with 94% of these individuals residing in rural areas. The report emphasises that to reduce this number, strict measures need to be taken either to generate employment opportunities for these people or to provide a support system that can make them self-reliant. Another approach is to implement inclusive business education and sensitise youth to it. Inclusive business models include the poor on the demand side as clients and customers and on the supply side as employees, producers and business owners at various points in the supply chain (UNDP, 2014).

In the realm of entrepreneurship education, it becomes necessary to include these concepts in the main curriculum. Therefore, students need to grasp the intricate dynamics of businesses operating at the grassroots level (Dalglish & Tortelli, 2016; Prahalad, 2019; Yadav & Goyal, 2015).

Understanding Entrepreneurship from the Bottom-of-the-pyramid

The authors here advocate that in countries like India, where a significant portion of the population relies on local market livelihood businesses for sustenance, gaining insights into the challenges faced by these livelihood businesses is paramount. Despite limitations in capital, minimal use of technology and small-scale operations, these businesses embody the essence of entrepreneurship, offering invaluable lessons to aspiring entrepreneurs. In the Indian context, a large segment of the population depends on generating income from roadside businesses (hereafter, referred to as vendors) dealing in perishable items such as selling fruits, vegetables, meat, flowers, quick snacks/fast food, and so on. These vendors operate in bustling local markets, where they navigate through a myriad of challenges daily. From managing limited capital and other resources, and fluctuating supply chains to tackling socio-economic constraints, they embody resilience and resourcefulness in the face of adversity.

Unlike tech-based businesses in emerging sectors, local market livelihood businesses operate within tight constraints. They face challenges emancipating from high liquidity and working capital crunch, little or no storage space for perishable items, competitions from nearby similar stalls and high uncertainty of footfall due to raising due to seasonal challenges and many more; these businesses need specific interventions to help them overcome these challenges. Despite the diverse nature of challenges and unique solutions needed, they encapsulate all elements of entrepreneurship, including opportunity identification, resource generation or allocation, risk-taking, innovation, customer relationship management, adaptability, decision-making, etc. For students learning and aspiring to venture into entrepreneurship, understanding the nuances of these grassroots businesses is indispensable.

Teaching Entrepreneurship Through Simulation Games: A Literature Review

Simulation games implemented in business education have proven to be a viable method of teaching complex business concepts. Learning through business simulation games has been in practice for six decades, starting in 1955 (Goi, 2018). There are various ways to adopt simulation games in classroom learning, including computer-led simulations, role plays and field activities. While the former two focus on developing learning in a controlled environment, the latter emphasises the importance of exposure and interaction with various others.

The learning generated through hands-on experience facilitates the transfer of learning among participants and bridges the gap between academic skills and industry needs. A study analysing 108 simulation game seminars in Germany found that the insights gained from simulation experiences provide professional learning benefits to entrepreneurs (Huebscher & Lendner, 2010). Social interaction and psychological safety positively impact knowledge development (Xu & Yanag, 2010). However, caution is needed when developing business simulation games. Sometimes students follow instructions without fully understanding the game, and cultural differences (Bagdonas et al., 2010), interpretation of factual data and understanding of formal and informal scenarios can hinder the learning process. Additionally, focusing solely on winning (Fox et al., 2018) can deviate players from generating a meaningful learning experience. For simulation games that integrate ethics as a core part of learning, failure (Cope, 2011) is considered a positive outcome. Encouraging players to engage in trial and error, risk-taking and experiencing failure in a safe environment is essential.

The Implemented Simulation Exercise

This simulation exercise represents an innovative initiative devised and implemented by the authors within their entrepreneurship course. This simple yet impactful simulation has provided students with a unique perspective on business and self-employment generation. Through immersive experiential learning, students have not only gained valuable knowledge but have also honed essential skills and cultivated attitudes crucial for entrepreneurial success.

In a university or institutional course on entrepreneurship, students were assigned an experiential learning activity centred on identifying business opportunities and suggesting solutions for local livelihood businesses operating in street markets. The primary goal of this exercise was to deeply immerse students in real-world entrepreneurial scenarios, fostering crucial skills such as recognising opportunities, solving problems and engaging with the community.

This simulation exercise implemented in business education exemplifies how addressing pressing social problems requires experimentation rather than debate. Through this experiential learning approach, students understand real-world livelihood scenarios and discover innovative solutions that can improve the lives of the poor while also enhancing business viability. The potential is immense: participants learn how entrepreneurial strategies can simultaneously drive social impact and business success, preparing them to leverage these opportunities in diverse markets. Local problems need local solutions. Nurturing local markets and cultures, leveraging local solutions and generating economic opportunities can augment this learning.

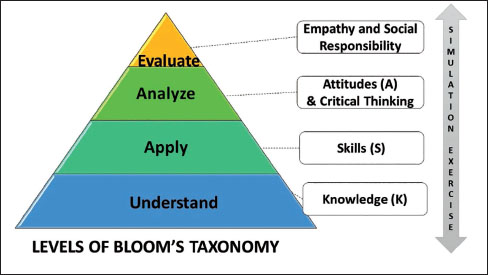

In crafting this simulation exercise, the authors aimed to embed entrepreneurial knowledge, skills and attitudes (KSA) (Acharya & Chandra, 2019) deeply into the overall learning and nurturing journey for students. As shown in Figure 1, the nurturance of KSA engages students at four out of six levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy model of learning framework. These levels include ‘understanding’ (acquired through knowledge), ‘applying’ (skills for applying entrepreneurial principles), ‘analysing’ (attitudes and critical thinking) and ‘evaluating’ (empathy development and social responsibility) (Bloom, 1994; Bloom et al., 1956).

Figure 1. Showing the KSA Integration Through Bloom’s Taxonomy Model of Learning.

Understanding how KSA enables successful entrepreneurship and the development of a micro and small enterprise is crucial, particularly at the base of the pyramid. Micro and small enterprises are expected to create the majority of the jobs needed for the 470 million individuals entering the labour market by 2030 (ILO, 2015). The UNDP report (2014) highlighted that policymakers worldwide view support for entrepreneurship as one of the most politically feasible and effective measures to reduce inequality. This underscores the importance of fostering entrepreneurial capabilities to drive economic growth and job creation at the grassroots level.

Hence, this simulation exercise aims to help students understand the challenges faced by local market livelihood businesses in India, fostering empathy for grassroots entrepreneurs and identifying opportunities for innovation and growth. By applying entrepreneurial principles such as opportunity recognition and customer relationship management, students will develop critical thinking, social responsibility and a deeper understanding of the socio-economic constraints these businesses face. This experiential learning cultivates an appreciation for the resilience and resourcefulness of micro-level or grassroots livelihood businesses. This experiential learning exercise is meticulously crafted to cultivate students’ entrepreneurial acumen by immersing them in real-world contexts and challenging them to propose solutions for complex challenges. Designed to foster a comprehensive understanding of entrepreneurship, it hones practical skills and cultivates a mindset conducive to entrepreneurial success. Through engagement in this exercise, students undergo holistic learning and skill development across multiple cognitive domains.

Following are the specifications for implementing the exercise.

Group size: Four to five students per group

Duration: This exercise spans multiple sessions, structured as follows:

Exercise implementation: After receiving the briefing in class, students formed groups and embarked on fieldwork to interview vendors in local markets. They conducted in-depth interviews, covering various aspects such as demographic and socio-economic analysis, daily operations, challenges faced and resource/capital arrangements. Upon returning to the classroom, students documented their findings and engaged in a discussion on improving the vendors’ supply chain lifecycle. Students identified numerous challenges faced by the vendors while operating their businesses. A brief overview of these markets is explained as follows.

Local Market where Data are Collected

The students who participated in the simulation exercise were pursuing MBA degrees from reputed educational institutions in two different cities in India: Kolkata and Nagpur.

Visiting Nagpur city provided students with broader exposure to a larger segment of vendors. Nagpur, one of Maharashtra’s fastest-growing cities, is famous for its tiger reserves, orange and mango farming, and textile apparel industry. Exploring these markets took more time and effort due to challenges in transportation and logistics, as well as language barriers.

Despite this, the issues and challenges faced by vendors were observed to be universal. The data collected and presented were collated holistically, and the solutions proposed were designed as a pool of solutions that could be easily implemented. The findings and solutions to overcome these challenges are summarised in the following section.

Findings Through Data Collection

Below listed are the findings observed by students, which show the challenges/issues faced by vendors while operating their businesses.

Brainstorming Solutions for Vendors’ Challenges

Following are the observations and findings on the challenges faced by vendors. Students engaged in a collaborative brainstorming session during classroom discussions to propose solutions aimed at addressing these issues. These solutions were presented through ideation (Gonzalez et al., 2024) and the business model canvas (Osterwalder et al., 2010), which encompass various aspects of business expansion and related strategies, such as:

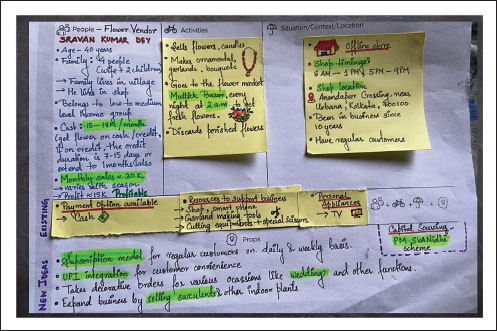

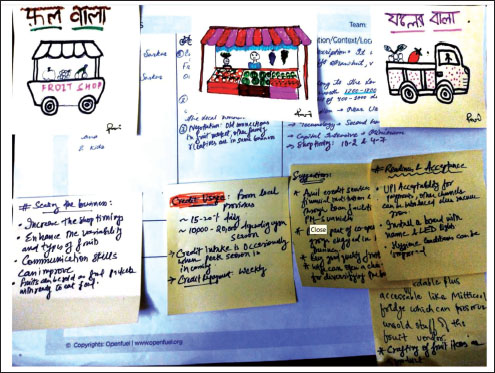

A quick summary of these interventions is described below in a few case studies from local vendors (Figure A1 and Figure A2).

Vendor Persona

Some of the vendor personas are discussed in three case studies as follows.

1) Case Study: Anand—Street Vendor in Fruit Trade

Anand migrated from an interior village to Nagpur to earn money. Hailing from a humble background, he embarked on this journey by selling his only possession and companion he brought from his village, the goat. He got ₹6,000 from selling his goat and utilised this as his initial investment. With diligent efforts and additional support from his wife, who sold her gold chain to fuel business expansion, they established a fruit trade venture. Their perseverance over 25 years has sustained this business. Operating with a monthly revenue of ₹30,000 and a notable profit margin of ₹20,000, Anand’s fruit business employs a demand-driven inventory model that needs stocking fruits based on customer preferences and seasonal demands.

Challenges faced: Anand faced a myriad of challenges in his fruit trade business, predominantly stemming from a shifting market landscape. The dwindling profit margins, exacerbated by heightened competition and evolving consumer preferences, are creating formidable hurdles to sustaining profitability over time. On top of that market saturation, coupled with the emergence of alternative food options, further intensifies this competitive landscape, posing a significant threat to his business viability. Additionally, changing consumer behaviours, with a preference for fast food alternatives, also contributed to a shrinking customer base.

Solutions suggested: In response to these challenges, the students suggested Anand devise several strategies aimed at adapting and thriving in the competitive market environment. Students suggested that by exploring additional product offerings, such as diversifying the fruit selection, he can endeavour to broaden the customer base and mitigate the impact of shrinking profit margins. He agreed and started implementing these changes in a small phase-wise manner by leveraging enhanced marketing techniques, including the utilisation of the WhatsApp platform, which allowed him to amplify product promotion efforts, reaching a wider audience and enhancing his visibility.

Moreover, he places a strong emphasis on quality and variety, striving to offer high-quality diverse fruits to attract discerning customers and differentiate his business from competitors. Central to his operational success were key partnerships with reliable fruit suppliers and strategic allocation of key resources, such as raw materials and attractive display arrangements, aimed at enhancing the overall customer experience.

In terms of distribution, Anand adopted a flexible strategy based on demand, minimising wastage and optimising costs to ensure freshness and adaptability in meeting customer needs. To address changing demographics and heightened competition, he implemented customer segmentation and attraction strategies, including discounts on bulk purchases, seasonal promotions and enhancing shopping experiences through attractive displays.

Despite maintaining stable revenue, the challenges of declining profit margins and intensified competition necessitate ongoing strategic adjustments in marketing and product offerings. Anand acknowledged the support he gained from students and the importance of reinvesting profits into the business, covering initial investments, permissions, infrastructure and ongoing operational costs, as essential for long-term sustainability and continued growth.

2) Case Study: Mala Dutta—Chicken Shop Owner

Mala Dutta operates a chicken shop in Kolkata, catering to customers from the lower-class segment. With a family of four, including her husband and two children, Mala faces challenges typical of small-scale businesses, compounded by limited access to basic utilities such as electricity and regular water supply at home. She stays inside this chicken shop with her family.

Challenges: She faces a multitude of challenges, including fluctuating demand for chicken products, stiff competition from larger poultry establishments and limited space for storage and display. The unpredictable shifts in demand have posed operational challenges, requiring adaptability to meet customer needs effectively. Moreover, the presence of larger poultry shops intensifies competition, necessitating innovative strategies to differentiate her offerings and retain customers. Additionally, space constraints hinder the efficient storage and display of products, impacting operational efficiency and customer satisfaction.

Low-cost Solution: Students suggested Mala adopt resourcefulness and resilience by implementing low-cost solutions. By exploring collaboration opportunities with local street food vendors and small hotels, Mala diversified her market reach and tapped into the business-to-business segment. Furthermore, considering the purchase of second-hand cold storage units presented a practical solution to address storage challenges and ensure the efficient preservation of products. Mala’s willingness to adapt to strategic initiatives underscores her proactive approach to overcoming obstacles and sustaining her business in a competitive environment. Through her resourcefulness and adaptability, Mala endeavours to navigate the complexities of the poultry industry and drive long-term success for her chicken shop.

3) Case Study: Nandini’s Tea Stall: Overcoming Challenges in a Roadside Business

Nandini, a resilient person, manages a humble tea stall adjacent to Ruby Market in Kolkata. Alongside two dedicated family members, she serves diverse customers consisting mainly of students, workers and daily wage earners seeking quick bites and tea after long days. Despite her tireless efforts, Nandini encounters several challenges in sustaining her roadside venture.

Challenges faced: One of the primary hurdles Nandini faces is the low footfall at her stall due to its location along a highway, resulting in minimal customer traffic. Furthermore, the perishable nature of the food items she prepares, including samosas and bread pakoras (popular fried snacks), adds pressure to sell them quickly, especially during rainy weather when footfall dwindles further. Despite her dedication, Nandini’s monthly earnings revolve around a modest ₹7,800, indicating a pressing need for improvement to sustain her business and livelihood.

Proposed solutions: Students proposed low-cost, effective solutions in response to these challenges, and Nandini readily accepted these innovative solutions to enhance her stall’s visibility and attract more customers. Students helped her to create an eye-catching handmade signage board with bold colours and bright lighting. She showed interest in creating a more inviting atmosphere, particularly during evening hours. Additionally, Nandini diversified her menu by offering a variety of snacks and introducing popular packaged chips and soft drinks to cater to diverse customer preferences.

To incentivise purchases and increase sales, Nandini introduced combo deals, such as pairing a snack with a soft drink, at discounted prices. Moreover, realising the need for hygiene and cleanliness, she ensured her stall’s surfaces, utensils and display areas were frequently cleaned. Despite her limited budget, Nandini invested in an economical cooling mechanism using a thermocol box insulated with ice packs to preserve the freshness of perishable snacks and beverages throughout the day. This box does not need electricity and works on ice, which helps to retain cool and freshness. Through her resourcefulness and resilience, Nandini exemplifies the spirit of entrepreneurship, demonstrating how determination and innovative thinking can overcome challenges in running a roadside business. Her journey serves as an inspiration for aspiring entrepreneurs navigating similar hurdles in the competitive landscape of small-scale enterprises.

Exhibit 1: Teaching Notes

The teaching notes summarised here are based on some theories and the reflection of learning that the authors of this article have gained through their subject matter and experience by interacting with the ecosystem. Most of the foundations explained are based on the teaching-learning methods developed by the authors themselves.

Understanding Business Opportunity Identification

Business opportunity identification happens at various levels, starting with opportunity recognition and identifying patterns to connect those missing dots that can serve as a link between problems and solutions. Hougaard (2005) defines opportunity seeking as the ability to see and understand problems and develop unexpected solutions from them. Here, we emphasise that aspiring entrepreneurs should prioritise pattern recognition as the initial step in opportunity identification. Pattern recognition entails actively seeking opportunities and establishing connections between different elements (Matlin, 2005). Once these patterns are recognised, they serve as the foundation for identifying novel business prospects and drawing links between seemingly unrelated events or activities. These connections subsequently facilitate the development of unexpected solutions to prevailing challenges.

Pattern Recognition in Opportunity Identification

The authors here augment that pattern recognition in opportunity identification (Baron, 2006) involves the ability to discern recurring themes or trends within a given context, which can then be used to identify potential business opportunities (Lumpkin & Lichtenstein, 2005; Shane, 2003, p. 9). In the context of this simulation exercise, students observed common challenges faced by vendors, such as decreased profit margins, limited access to credit facilities and infrastructure limitations, which may initially appear dissimilar. However, through pattern recognition, students begin to recognise underlying similarities or patterns across different vendors. For example, they observed that multiple vendors struggled with inadequate storage facilities for perishable items or were facing harassment from money lenders. By identifying these patterns, students inferred broader challenges prevalent among local market businesses and subsequently proposed solutions that address these common issues.

Pattern Recognition at a Macro Level

The authors here argue that opportunity recognition at a macro level can help to generate solutions. Macro-level opportunity recognition involves identifying trends, patterns and challenges at a broad societal or industry level (Jabeur et al., 2022; Omri et al., 2024). Pattern recognition at a macro level, within the context of this simulation exercise, involves identifying overarching trends or patterns that span across multiple local market businesses. Students observed various factors such as fluctuating demand, rising competition and limited access to credit facilities. Through this process, students begin to recognise broader patterns that transcend individual businesses and common challenges faced by vendors operating in similar geographical locations or within specific industries.

For instance, students observed that vendors located in areas with low foot traffic tend to experience decreased profit margins, regardless of the specific products they sell. Similarly, they identified a pattern of reliance on informal lending sources, such as money lenders charging exorbitant interest rates, among vendors across different market segments.

The authors here observed that by recognising these macro-level patterns, students gained insights into universal issues affecting local market businesses and have developed low-cost, technology-limited strategic solutions (Baron, 2006) that address these broader challenges. This approach has enabled students to think critically about the underlying dynamics shaping livelihood businesses and to propose interventions that have the potential to create meaningful impact across diverse business contexts. For aspiring entrepreneurs, pattern recognition can be leveraged by analysing demographic shifts, technological advancements and regulatory changes to identify emerging needs and market gaps. By understanding these macro-level dynamics, entrepreneurs can develop innovative solutions that address widespread problems and capitalise on growing trends, ensuring the relevance and success of their ventures in the long term (Jabeur et al., 2022).

Let us understand this by taking the demographic (Baron, 2006) as one of the factors of pattern recognition. For instance, in India, the needs of different demographic groups vary significantly, such as youth, women and the elderly population. As far as Indian demographics are concerned, it became crucial to identify business solutions that would be needed by an ageing population. It is estimated that by 2050, 20% of India’s population will be over 60 years old (Ranjan & Muraleedharan, 2020; Sahoo et al., 2021; UNFPA India, 2023). With changing family structures, shifting age dependency ratios and inadequate state-provided services, there is a growing demand for businesses catering to the elderly population. Understanding this will help aspiring entrepreneurs to develop business ideas in sectors such as elderly care, healthcare, personalised care centres, social security, financial investment and management, retirement homes, and so on. Innovative and sustainable, or low-cost solutions, can become a boon for these sectors.

Opportunity Recognition from the Customer Preference Perspective

Opportunity recognition from the customer preference perspective (Baron, 2006; Jabeur et al., 2022) in the context of this simulation, exercise involves understanding and analysing the evolving needs and preferences of target customers. Students explore why certain business models, such as ride-hailing services like Ola and Uber or food delivery platforms like Zomato and Swiggy, are in high demand among consumers. These services thrive on repeat customer needs, leading to a loyal customer base and when this gets multiplied, these kinds of business models will work in a mass segment. By examining the repeated needs and behaviours of customers, students identify those patterns that indicate opportunities for entrepreneurial ventures.

Similarly, in Germany, the white goods industry offers rental options for quintessential kitchen supplies, bedding and household equipment, catering to the needs of a population living in rented apartments. This kind of model can work in places such as Mumbai and Bengaluru (and similar Indian metropolitan cities) where the majority of the population lives in rented apartments and does not want to purchase equipment for longer-term usage.

By examining customer preferences from a macro perspective, students gain insights into emerging market trends and consumer behaviours, enabling them to identify entrepreneurial opportunities that align with evolving customer needs. Navigating how opportunities or pattern recognition happen, such as individual opportunity (Shane, 2003), or in consideration with cognitive skills (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000), networking skills (Chea, 2008), organisational learning process (Lumpkin & Lichtenstein, 2005), career choices (Lee & Venkataraman, 2006) and so on, entrepreneurs can anticipate needs, connect with external developments and formulate strategies for success.

Hence, looking at these theoretical contributions, this simulation exercise will engage students in opportunity identification and pattern recognition by analysing data collected from local livelihood businesses. By identifying recurring challenges and customer preferences, students will develop innovative solutions tailored to meet the specific needs of these businesses. This process will not only deepen their understanding of entrepreneurship but also equip them with valuable skills in identifying market opportunities and formulating effective strategies.

Following are the teaching notes that would be useful for instructors.

Teaching Notes for Simulation Exercise

This simulation exercise is designed to immerse students in the real-world context of entrepreneurship by engaging them in the process of identifying business opportunities and proposing solutions for local livelihood businesses. It is particularly relevant in countries like India, where a significant portion of the population depends on such businesses for their livelihood. Through this exercise, students will gain insights into the challenges faced by these businesses and develop entrepreneurial KSA (Acharya & Chandra, 2019) crucial for success in the field. This teaching note would be resourceful for instructors.

Immersing KSA Through this Activity

This activity facilitated holistic learning and skill development, equipping students with the KSA necessary to thrive in the entrepreneurial landscape and make meaningful contributions to their communities (Acharya & Chandra, 2024). Through the presentation of these innovative solutions, students showcased their proficiency in applying entrepreneurial principles and employing creative problem-solving techniques to address the real-world challenges encountered by local livelihood businesses. By integrating the KSA, an entrepreneurship learning framework model developed by Acharya and Chandra (2019) (see Figure 1), this simulation exercise immerses students in real-world scenarios faced by local livelihood businesses. Now let us see what these three elements of the framework are.

Exposing Students to Local Businesses

Instructors must emphasise here the significance of understanding local businesses, especially in countries like India, where they play a pivotal role in the socio-economic fabric. To give an in-depth understanding to students, educators must highlight the operational dynamics of these businesses, particularly the relevance of the hub-and-spoke model (Elrod & Fortenberry, 2017), which finds its roots in the work of Philip Kotler’s human-to-human marketing (Kotler et al., 2021). The hub-and-spoke model was first introduced by Delta Airlines in the year 1955 explaining the push-and-pull approach to innovation. The model floats in the idea that ideas and solutions flow between business units and a central innovation system.

Understanding the Hub-and-spoke Model

In this section, we discuss how the hub-and-spoke model (Elrod & Fortenberry, 2017; Nicolopoulou et al., 2017) functions in local businesses, wherein a central hub coordinates with multiple peripheral spokes to streamline operations and reach customers. Here in this exercise, the solution in the hub-and-spoke model suggests that a central hub at the centre of the city can be created as a central warehouse, and distribution centres can be created through a spoke method. These hubs should be strategically located to maximise accessibility for both vendors and customers. Once the hub locations are identified, vendors can establish spoke connections by collaborating with neighbouring vendors or forming partnerships with nearby businesses. These spoke connections allow vendors to leverage each other’s strengths and resources, creating a network of support within the local market ecosystem. These spoke locations in nearby areas will provide local access to essential supplies and services. Illustrate the application of this model in direct-to-customer businesses, where the focus is on enhancing customer satisfaction, retention and attraction.

Thus, implementing a hub-and-spoke model will allow vendors to streamline their supply chain operations by centralising procurement and distribution activities at the hub locations. This centralised approach enables vendors to consolidate orders, negotiate better deals with suppliers and minimise transportation costs. By pooling resources and inventory at the hub locations, vendors can ensure consistent availability of products across their network of spokes. This improves customer satisfaction by reducing stockouts and providing a wider selection of goods to choose from. Thereby also creating a seamless customer experience.

Conclusion

This simulation exercise offers a unique opportunity for students to bridge theoretical knowledge with practical experience in entrepreneurship education. By engaging with local businesses and leveraging theoretical frameworks, students not only develop essential entrepreneurial competencies but also gain a deeper appreciation for the multifaceted nature of entrepreneurship in driving socio-economic progress. The exercise illuminated the real-world challenges faced by livelihood businesses, such as fluctuating demand, infrastructure limitations and access to credit. Students proposed innovative solutions, including improved supply chain management, enhanced customer engagement strategies and better access to financial resources. The hands-on experience of pitching these solutions and receiving feedback from vendors enriched their learning and underscored the importance of adaptability and resilience in entrepreneurship.

Implementing these solutions in real-time provided students with invaluable insights into the complexities of managing small-scale businesses, from operational hurdles to strategic decision-making. Experiential learning fosters critical thinking (Fox et al., 2018), empathy and a problem-solving mindset (Acharya & Chandra, 2019; Cope, 2011), preparing students to navigate diverse business environments effectively. Moreover, the exercise emphasised the social responsibility (Bagdonas et al., 2010) of entrepreneurs in uplifting local communities, highlighting the role of entrepreneurship (Huebscher & Lendner, 2010) in addressing poverty and inequality (Senapati & Parida, 2024). Ultimately, this simulation underscores the significance of experiential learning in entrepreneurship education. By immersing students in the realities of local livelihood businesses, it cultivates a holistic understanding of business dynamics and equips future entrepreneurs with the skills and mindset necessary for sustainable success and socio-economic impact.

Limitations

This simulation exercise is constrained by geographic, cultural and time limitations, potentially impacting the generalisability of findings.

Significance

The exercise provides a hands-on approach to understanding grassroots entrepreneurship, fostering empathy and critical thinking.

Theoretical, Practical and Social Implications

This exercise theoretically enriches entrepreneurial education, practically enhances problem-solving skills and socially promotes economic development at the grassroots level.

Annexure. Glimpse of Some Business Model Canvas Developed by Students.

Figure A1. Business Model Canvas.

Figure A2. Business Model Canvas 3.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their gratitude to students and vendors. Students particularly as they enthusiastically implemented this challenging exercise, and to all vendors who have participated in sharing their information. The authors are grateful to the anonymous referees of the journal for their extremely useful suggestions to improve the quality of the paper. Usual disclaimers apply.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Yamini Chandra  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7860-9559

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7860-9559

Acharya, S. R., & Chandra, Y. (2019). Entrepreneurship skills acquisition through education: Impact of the nurturance of knowledge, skills, and attitude on new venture creation. International Journal of Educational and Pedagogical Sciences, 13(2), 198–208. https://doi.org/doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2576932

Acharya S. R., & Chandra Y. (2024). Role of technology business incubator in enhancing entrepreneurship ecosystem. In K. Kankaew, P. Nakpathom, A. Chnitphattana, K. Pitchayadejanant, & S. Kunnapapdeelert (Eds.), Applying business intelligence and innovation to entrepreneurship (pp. 21–34). IGI Global.

UNFPA India (2023). (2023). Public health care utilization by elderly in India: An analysis of major determinants from LASI Data [Analytical Paper Series No. 7]. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00619-7

Bagdonas, E., Patašien?, I., Patašius, M., & Skvernys, V. (2010). Use of simulation and gaming to enhance entrepreneurship. Electronics and Electrical Engineering, 102(6), 155–158.

Baron, R. A. (2006). Opportunity recognition as pattern recognition: How entrepreneurs “Connect the Dots” to identify new business opportunities. Academy of Management Perspectives, 20(1), 104–119.

Bloom, B. S. (1994). Reflections on the development and use of the taxonomy. Yearbook: National Society for the Study of Education, 92(2), 1–8.

Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook 1: Cognitive domain. Longman.

Chea, A. C. (2008). Entrepreneurial venture creation: The application of pattern identification theory to the entrepreneurial opportunity-identification process. International Journal of Business and Management, 3(2), 37–53.

Cope, J. (2011). Entrepreneurial learning from failure: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(6), 604–623. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JBUSVENT.2010.06.002

Dalglish, C., & Tortelli, M. (2016). Entrepreneurship at the bottom of the pyramid. Entrepreneurship at the Bottom of the Pyramid, 1–187. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315727417/ENTREPRENEURSHIP-BOTTOM-PYRAMID-

CAROL-DALGLISH-MARCELLO-TONELLI

Dhiman, V., & Arora, M. (2024). Exploring the linkage between business incubation and entrepreneurship: Understanding trends, themes and future research agenda. LBS Journal of Management & Research; epub ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/LBSJMR-06-2023-0021

Elrod, J. K., & Fortenberry, J. L. (2017). The hub-and-spoke organization design: An avenue for serving patients well. BMC Health Services Research, 17(Suppl. 1), 457. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2341-x

Fox, J., Pittaway, L., & Uzuegbunam, I. (2018). Simulations in entrepreneurship education: Serious games and learning through play. Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy, 1(1), 61–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515127417737285

Goi, C.-L. (2018). The use of business simulation games in teaching and learning. Journal of Education for Business, 94(5), 342–349.

Gonzalez, G. E., Andres, D., Moran, S., Houde, S., He, J., Ross, S. I., Muller, M., Kunde, S., & Weisz, J. D. (2024). Collaborative canvas: A tool for exploring LLM use in group ideation tasks. https://mural.co

Hougaard, S. (2005). The business idea: The early stages of entrepreneurship. Springer.

Huebscher, J., & Lendner, C. (2010). Effects of entrepreneurship simulation game seminars on entrepreneurs’ and students’ learning. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 23(4), 543–554.

ILO. (2015). Mainstreaming of migration in development policy and integrating migration in the post-2015 UN development agenda. ILO-background note: The contribution of labour migration to improved development outcomes. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_protect/—protrav/—migrant/documents/genericdocument/wcms_220084.pdf

Jabeur, S. B., Ballouk, H., Mefteh-Wali, S., & Omri, A. (2022). Forecasting the macrolevel determinants of entrepreneurial opportunities using artificial intelligence models. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 175, 121353. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TECHFORE.2021.121353

Kotler, P., Pfoertsch, W., & Sponholz, U. (2021). The new paradigm: H2H marketing. H2H Marketing, 29–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-59531-9_2

Lee, J. H., & Venkataraman, S. (2006). Aspirations, market offerings, and the pursuit of entrepreneurial opportunities. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(1), 107–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JBUSVENT.2005.01.002

Lumpkin, G. T., & Lichtenstein, B. B. (2005). The role of organizational learning in the opportunity–Recognition process. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(4), 451–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1540-6520.2005.00093.X

Matlin, M. W. (2005). Cognition (6th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Nicolopoulou, K., Karata?-Özkan, M., Vas, C., & Nouman, M. (2017). An incubation perspective on social innovation: The London Hub—a social incubator. R and D Management, 47(3). https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12179

Omri, H., Omri, A., & Abbassi, A. (2024). Macro-level determinants of entrepreneurial behavior and motivation. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11365-024-00990-6

Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., & Clark, T. (2010). Business model generation: A handbook for visionaries, game changers, and challengers. Wiley.

Prahalad, C. K., & Hart, S. L. (2004). The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid. Booz & Company.

Prahalad, D. (2019). The new fortune at the bottom of the pyramid. Consumer & Retail, 94.

Ranjan, A., & Muraleedharan, V. R. (2020). Equity and elderly health in India: Reflections from 75th Round National Sample Survey, 2017-18, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Globalization and Health, 16(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12992-020-00619-7/TABLES/7

Sahoo, H., Govil, D., James, K. S., & Prasad, R. D. (2021). Health issues, health care utilization and health care expenditure among elderly in India: Thematic review of literature. Aging and Health Research, 1(2), 100012. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AHR.2021.100012

Senapati, A. K., & Parida, D. (2024). Labour force participation, gender equality and women’s empowerment through micro-entrepreneurship: Evidence from Odisha, India. IMIB Journal of Innovation and Management, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/ijim.231200316

Shane, S. A. (2003). A general theory of entrepreneurship: The individual-opportunity nexus. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Shane, S. A., & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 217–226. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2000.2791611

Sharma, R., Mishra, N., & Sharma, G. (2023). India’s frugal innovations: Jugaad and unconventional innovation strategies. IMIB Journal of Innovation and Management, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/ijim.221128071

UNDP. (2014). Barriers and opportunities at the base of the pyramid. The role of private sector in inclusive development. United Nations Development Programme.

World Poverty Clock. (2024). India. Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development.

Xu, Y., & Yanag, Y. (2010). Student learning in business simulation: An empirical investigation. Journal of Education for Business, 85(4), 223–228.

Yadav, V., & Goyal, P. (2015). User innovation and entrepreneurship: Case studies from rural India. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 4(5). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-015-0018-4