1 Department of Rural Development Studies, University of Kalyani, Nadia, West Bengal, India

2 Mahatma Gandhi National Council of Rural Education, MoE, GoI, Hyderabad, Telangana, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

Financial inclusion provides the legitimate provisions of basic banking services with adequate financial securities to the unbanked population at a reasonable cost. Since the early decade of the 20th century, the cooperative system has been engaged to percolate financial inclusion in various strata of our society. Several initiatives regarding financial inclusion have been implemented in the post-independence period; however, the Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) 2014 has been considered as one of the most fruitful and effective initiatives by the Government of India for opening no-frill bank accounts with zero balance facilities for financially excluded people in our country, and the cooperative banks have been playing a vital role in the process of implementing the said Yojana. The present study, based on Hooghly District Central Cooperative Bank (HDCCB) and Burdwan Central Cooperative Bank (BCCB) of West Bengal, has comprehended to investigate the role of the DCCBs in the process of financial inclusion with respect to a number of financial operations and annual changes of savings accounts over the second decade of the 21st century. The study has identified statistically significant segments of the financial operations. Those segments are consequences of several fluctuations in financial operations due to the changes in banking policy, implementation of PMJDY, demonetisation, loss of agriculture production, adverse effects of COVID-19 and also the national economic downturn. Finally, it has been observed that the implementation of PMJDY significantly gave rise to the business of the HDCCB and also acted as a threshold point of financial inclusion than its counterpart in the Burdwan district of West Bengal.

Financial inclusion, demonetisation, self-help group, community sensitisation, Jan-Dhan Yojana, low-risk customers

Introduction

One of the contemporary versions of financial inclusion has been initiated by C. Rangarajan (Government of India, 2008), the former governor of the Reserve Bank of India, as the process of ensuring access to financial services and timely and adequate credit where needed by vulnerable groups such as ‘weaker sections’ and ‘low income groups’ at an affordable cost. It may be an act of including, as emphasised by Ananth and Sabri-Oncu (2013), at least one adult member from every household in the formal banking sector by opening an account. They identified that public sector banks are primal players in the implementation of several interest-subvention government schemes among the unbanked population on a large scale. It has been argued that the success of financial inclusion depends on expanding scopes of financial literacy, interventions of agencies to lead the programmes and ultimately overcoming the asymmetries in the real world (Ananth & Sabri-Oncu, 2013). Mishra et al. (2024) argued that several ‘Fintech’ organisations are creating new vistas of employment by opening new outlets, such as kiosks, PoS gadgets and mobile vans across rural India, to address the aforementioned issues. Demirguc-Kunt et al. (2015) have criticised the nature of institutional characters of banking sector, that is, accessibility of appropriate financial services to adult members in a regulated environment. Financial inclusion has immense potential to promote poverty reduction strategy and also has ample scope for poverty reduction if duly accomplished by responsible authorities (Collins et al., 2009). Researchers have opined that there have been significant contributions to establish a link between the micro- and macro-economic structure of a nation by affecting the financial development indices1 when vulnerable gaps are financially included (Beck et al., 2000; Clarke et al., 2006; King & Levine, 1993). The study by Senapati and Parida (2024) opined that decision-making on financial issues empowers the women population to set up their own micro-enterprises.

Considering the aforementioned aspects of financial inclusion, public good theory (Ozili, 2020) gives the most appropriate premises to explain the initiatives that have been taken by the Government of India in the process of implementation of financial inclusion. The said theory has two distinct propositions, namely (a) the whole population will be the beneficiary of formal financial services, and (b) it is the responsibility of the regulating authority to ensure that universal access of formal financial services should have to reach every beneficiary. After independence, a number of initiatives on financial inclusion have been taken by the Government of India to percolate the formal financial services to every Indian. Introduction of cooperative banks in the agricultural credit sector in the late 1950s, nationalisation of commercial banks under the Lead Bank Programme (1969), establishment of Regional Rural Banks (1975), reduction in cash reserve ratio in statutory liquidity during the post-liberalisation period, Bank-SHG Linkage Programme (1992), introduction of the Kishan Credit Card Programme (1998) and finally implementation of the Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) (Government of India, 2014) are some of the remarkable initiatives in India in the course of financial inclusion (Mukhopadhyay, 2016; Rao, 2007). The visions and implementing strategies of the said initiatives make every Indian the beneficiary of financial inclusion. Also, these initiatives create a large-scale public fund to facilitate the process of financial inclusion for the public at large.2 Thus, the aforementioned initiatives satisfy the propositions of the Public Good Theory to foster financial inclusion in India. Teki and Mishra (2012) have rightly observed that the increase in the number of financial institutions has a positive impact on the process of financial exercise by extending financial services to the public at large and thereby contributing to financial inclusion.

The present study has been divided into a number of sections. The introductory section deals with an overview, framework and theoretical background, as well as initiatives taken by the Government of India to facilitate the process of financial inclusion. The review of literature has been discussed in the next section under two distinct headings, namely, the evolution of cooperative models in India along with the West Bengal perspective and aspects on cooperative banks’ initiatives in India. The next section deals with the objectives of the study, duly considering the literature gap. Thereafter, the rationale of the study section states the implications of this study, which is followed by the methodology in details. The penultimate section deals with the analysis and discussions based on the data as collected. Finally, the conclusion has been drawn with some suggestive measures for better implication and operations of financial inclusion, focusing on cooperative banks in general and selected district cooperative banks in particular.

Review of Literature

This section has been divided into two distinct arenas as discussed below.

A Evolution of Cooperative Models in India and West Bengal

It has been identified by eminent scholars (e.g., Kamath & Kurian, 1996; Roy, 1982; Teki & Mishra, 2012) that the cooperative model is an established microfinance approach to leverage the financial betterment of society in general. It had been institutionalised in India by enacting the Cooperative Credit Societies Act (Act X of 1904) (Governor General of India in Council, 1904). It is interesting to note that the prevailing three-tier cooperative model3 has been based on the recommendations of Maclagan Committee4 (1915). After independence, the All India Rural Credit Survey Committee5 (1954) identified the cooperative model as an engine of rural development to mobilise the unbanked population in a formal credit structure. In 1979, the highly empowered Shivaraman Committee recommended to develop a specified financial institution to oversee the various credit issues of rural population; based on the recommendations of the committee, the National Bank for Agricultural and Rural Development (NABARD) was established in 1982 (NABARD, n.d.). Since inception, the NABARD has consistently been dedicated to promote sustainable and equitable financial interventions with innovative approaches towards financial inclusion in rural India.

The aforementioned cooperative model (1915) came into operation as a cooperative federation—the Bengal Provincial Cooperative Federation Ltd—in the then united Bengal since 1918. This federation was converted into The Bengal Provincial Cooperative Bank Ltd. in 1923, with a significant extension in operational areas covering the whole Bengal Province. In 1964, the said bank was finally renamed as The West Bengal State Cooperative Bank Ltd,6 and after two years, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) enlisted this bank as Scheduled Bank (The WBSCB, n.d.).

B Initiatives Taken by Cooperative Banks in India

At present, there are 34 State Cooperative Banks and 366 District Central Cooperative Banks remain operational across the country under the regime of the rural cooperative credit system (RBI, n.d.). However, Demirguc-Kunt and Klapper (2012) identified, as documented in Census 2011, that only 58.7% of Indian households have at least one bank account. Various cooperative structures and their respective functions have been identified by Nagaraj (2015) to portray the evolution of formal credit support in both urban and rural areas. The study has also observed that the introduction of the single window system in credit support has a positive contribution towards the significant growth of the performance of banks. Another study (Dubey et al., 2009) has critically identified that cooperative loans disbursed with low rates of interest can be a potential weapon to counteragent the debt trap as well as to check out-migration of the male population. Nowadays, every banking institution is facing sheer competition in the field of their operations; cooperative banks are also no exception. How the Strength, Weakness, Opportunities and Challenges analysis can help to identify a suitable strategy to combat present challenges was focused on a study by Lakshmi and Manoj (2015). Distinguished from all above, Mitra (2012) has documented the success journey of an urban cooperative bank by analysing its performance in comparison with other banks in the state of Maharashtra. Wealthy farmers are principal beneficiaries of short-term as well as long-term credit support, as identified by Dubhashi (2001), and it is also considered a major pitfall of operations in cooperative institutions. In another study, it has been identified that major sections of the excluded population have opened no frills accounts in cooperative banks (Majumder & Gupta, 2013). It has also been identified by Mohapatra (2016) that the cooperative system in India has a total deposit of ₹296,803 crore and the total number of loan accounts is ₹382,617 (as of 31 March 2016).

Thus, it is evident that the evolution of the cooperative model since the pre-independence period led to delivering universal access to formal financial services for the public at large. At the same time, the governments, both central and state, are always putting their efforts to oversee the inclusion processes to make it sustainable in future. Thus, it can necessarily be concluded that the initiatives related to financial inclusion in India clearly follow the propositions of the Public Good Theory.

Against this backdrop, the present study has been undertaken and needless to mention that no comparative study among District Central Cooperative Banks with longitudinal data has ever been made in the state of West Bengal identifying the periods of pre- and post-launching of PMJDY.

Objectives of the Study

The primary objective of the study is to investigate the status of financial inclusion of Hooghly and Burdwan district populace as initiated by the Hooghly District Central Cooperative Bank (HDCCB) and the Burdwan Central Cooperative Bank7 (BCCB), respectively, giving stress on access to banking services, availability of credit and participation in financial literacy programmes by the excluded group. The literature gap as pointed out in the previous section has been considered.

The supplementary objectives of the study are to see the pattern of growth of both the banks operating in their respective districts as well as to obtain a comparative insight into the performances of the two banks during the second decade of the 21st century. Finally, some suggestive measures have been offered to improve the overall operations and activities of the banks.

Rationale of the Study

A considerable number of studies have been taken for financial inclusion in India since the pre-independence period, but no study has ever been made on assessment of performances by District Central Cooperative Banks before and after enactment of the PMJDY, 2014 in the selected districts of West Bengal. The present study is a humble attempt to bridge the gap between the mission objectives of PMJDY and implementation strategies by the District Central Cooperative Banks. The obtained results, based on the analysis of collected data, highlight the issues wherein appropriate measures need to be taken to implement the financial inclusion programme more efficiently and effectively. The study, it is believed, may be helpful to the responsible authorities to restructure their policies and implementation strategies.

Methodology

The Directorate of Rice Development under the Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India, while presenting an overview of rice productivity in different ecosystems of India (Directorate of Rice Development, n.d.), has identified that out of 18 districts in West Bengal, only four, namely Burdwan (2,842 kg/Ha), Birbhum (2,743 kg/Ha), Nadia (2,705 kg/Ha) and Hooghly (2,514 kg/Ha), are categorised as high producers of rice (yield more than 2,500 kg of rice per hectare). As per Census 2011, in rural areas more than 75% of the total male population must be engaged in agriculture; since the operations of the District Cooperative banks vastly cover the rural areas, two districts out of four as stated, are selected on a simple random sampling method. As of 2011, in Burdwan Central Cooperative Bank, nearly 82% of the total members belong to agricultural farmers, while it is 78% in Hooghly District Central Cooperative Bank (HDCCB) (Department of Planning and Statistics (Purba & Paschim Burdwan), 2019a, b).

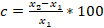

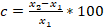

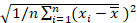

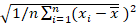

Several important heads of accounts in banking operations, such as share capital, reserve fund, deposits, borrowings, loans and advances, investments, gross income, gross expenditure and gross profit, have been tabulated to see the pattern of growth of financial inclusion; also applied descriptive statistics, namely, change in per cent (

), mean (

), mean (

=1/n

=1/n

), standard deviation (SD =

), standard deviation (SD =

) and skewness (Fisher Skewness Coefficient =

) and skewness (Fisher Skewness Coefficient =

), using the PASW Statistic 18 application, to examine the stability in business. Dendrograms have been obtained by hierarchical clustering, with the between-groups linkage method and Euclidean distance as an interval. Based on the threshold value 5 among the 25-point scale of similarity, the number of suitable clusters has been identified from the dendrograms; thereafter, k-means clustering has been applied to obtain statistically significant segments on the basis of the identified number of clusters from the dendrograms with the iterate and classify method. Finally, different financial services and the number of savings accounts of both banks have been tabulated to see the pattern of financial inclusion in the concerned districts over the decade.

), using the PASW Statistic 18 application, to examine the stability in business. Dendrograms have been obtained by hierarchical clustering, with the between-groups linkage method and Euclidean distance as an interval. Based on the threshold value 5 among the 25-point scale of similarity, the number of suitable clusters has been identified from the dendrograms; thereafter, k-means clustering has been applied to obtain statistically significant segments on the basis of the identified number of clusters from the dendrograms with the iterate and classify method. Finally, different financial services and the number of savings accounts of both banks have been tabulated to see the pattern of financial inclusion in the concerned districts over the decade.

Data Source

The study has been done using both primary and secondary data. The longitudinal data and different initiatives regarding financial services, so collected by administering a structured questionnaire on responsible officials and annual financial reports (duly audited) of both the banks between 2011–2012 and 2020–2021 are the primary sources of data.

Secondary data sources comprise several cooperative acts (operative in pre- and post-independence period), mission documents of different government programmes, RBI guidelines, annual reports of NABARD, scholarly articles by eminent researchers, books, journals, Census Report, 2011 and the District Statistical Handbooks of Hooghly, Purba and Paschim Bardhaman districts

(Department of Planning and Statistics, 2018, 2019a,b).

Perspectives of Financial Operations of Banks: Analysis and Discussion

Economic Background of Account Holders

According to the prevailing rules, a citizenry with some qualifications can be a member of any grassroots cooperative society, namely, Primary Agriculture Cooperative Societies (PACS), Employees’ Cooperative Credit Societies, Local Adibashi Multipurpose Societies, weavers’ cooperatives, self-help groups (SHGs), cold storage cooperatives, engineers’ cooperatives, labour contractors’ cooperatives, labour cooperatives, etc. and open an account in a cooperative bank. It has been observed that major account holders are belonging to low-risk customers.8

Pattern of Growth and Business Stability

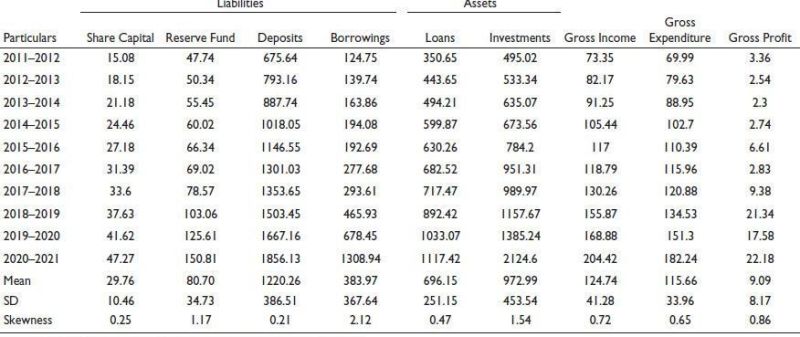

From Table 1, it has been observed that the moderate rate of growth (13.59% and 11.93%) and positive value of skewness (0.25 and 0.21) in share capital and deposit accounts, respectively, in HDCCB are the clear indications of a slow but steady increment in the number of cooperative members and positive growth of business. At present, the total number of deposit accounts is 5,63,336 (i.e., savings: 508,962, current: 3,272, other deposit: 51,102 as of 31 March 2023). The salary of primary school teachers has now been disbursed through cooperative banks. These newly opened accounts are clearly reflecting the growth of share capital and deposit accounts. RBI Banking Regulation Act, 1949, has been directed to all financial institutions to transfer 20% of their annual net profit to the reserve fund to enhance financial sustainability. 13.93% average increment in reserve fund and lower SD (₹34.73 crores) value than mean (₹80.70 crores) are the indicators of financially stable condition.

Increase in borrowings (average 32.68%), especially in 2016–2017 onwards, and disbursed loan amount (average 14.01%) are the clear reflection of high credit demands from lower-tier cooperatives. Actually, enactment of the Interest Subvention Scheme, 2018, by the Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) has a significant effect on the increase of credit demands. Kishan Credit Card (KCC) loans are disbursed at a 7% annual rate of interest, but there is a provision of a 3% interest subsidy for timely repayment of loans. Also, SHGs are borrowing loans at 11% annual rate of interest, but there is also a provision of a 9% interest subsidy. Needless to mention availing of interest subsidy schemes entails beneficiaries by reducing volume of annual interest on one hand and also helps the financial institutions to comprehend their business sustainability by way of better loan recoupment (93% in 2020–2021) which reduced the NPA (e.g., gross NPA is 3.55% and net NPA is 0% as of 31 March 2021) on the other. The positive growth rates of gross income (average 12.20%), gross expenditure (average 11.33%) and profit (average 48.54%) indicate that by implementing the PMJDY, the overall business operations have significantly been boosted up. However, in 2020–2021, a loss (17.62%) was incurred due to the effect of COVID-19. A slightly lower value of SD (₹8.17 crores) than the mean value (₹9.09 crores) is a clear prediction of stability with some degree of risk in profit. Presently, the bank has 24 branches across the Hooghly district.

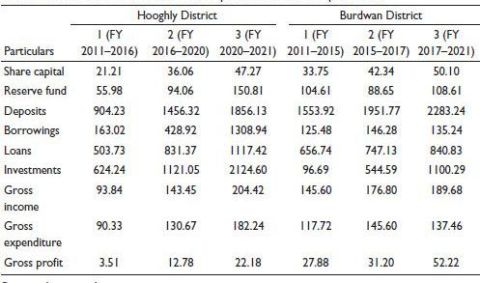

Table 1. Details of Financial Operations of Hooghly District Co-Op Bank. (All Figures are in Crores of Rupees) Period: FY 2011–2012 to 2020–2021

Source: Prepared by the authors based on Annual Financial Reports of HDCCB.

Note: SD = Standard Deviation.

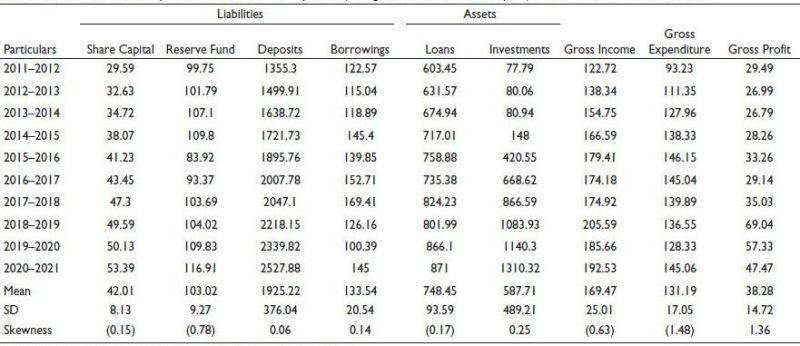

In the case of Burdwan district (Table 2), at present, the BCCB has 40 branches. As of 31 March 2023, the concerned bank has a total of 3,262,177 deposit accounts (savings: 853,789, current: 10,536 and other deposit: 2,397,852); however, there has been a very slow rate of growth in share capital (average 6.81%) and deposits (average 7.21%) over the decade. The low rate of interest in savings accounts from 2015 has significantly affected the growth of share capital and deposit accounts. The negative value of skewness (−0.15) is clear evidence of fall in the rate of growth of share capital during 2018–2019 and onwards. In 2015–2016, in the course of introduction of PMJDY, 2014, the bank had faced some financial vulnerabilities entailing a negative rate of change in the reserve fund (−23.57%). However, the bank has a stable financial condition as the value of SD (₹9.27 crores) is much lower than the mean value (₹103.02 crores) of the reserve fund. During the early years of the decade, KCC loans, mid-term agriculture loans, crop loans and cash credit (CC) loans were mainly disbursed from the bank; however, after the implementation of the SHG-Bank Linkage Scheme, various other short-term credit supports are now disbursed (₹810 crores in 2020–2021) by the bank on a large scale. It has been found that due to the drastic fall in agricultural production during 2011–2012 onwards, the demand for agricultural loans was reduced remarkably. As a result, the reduced demand for loans from the markers compelled the BCCB not to borrow any sizeable amount of fund from the RBI or any other commercial loans. This is evident from Table 2 that the borrowings of BCCB has been cut down remarkably. However, the situation has changed from the financial year 2014–2015. In 2017, some changes have been made in the terms and conditions of loan disbursements. Again, it has long been practiced by farmers to borrow funds on account of crop loans in a season that have been used to redeem the earlier crop loans. To stop this practice, a new policy was introduced by the BCCB in 2017–2018 where it is stated that the new loan would be granted to the borrowers only when the previous crop loans have been repaid entirely. Introduction of such a policy yields a negative growth in borrowings (i.e., −25.53% in 2018–2019) as well as loan approval (−2.7% in 2018–2019). High seasonality and climatic changes have adversely affected consistency in crop yielding; the nationwide lockdown for COVID-19 also slowed down the growth of the economy. As a result, loan recovery was only 62% during 2020–2021 resulting in an increase of NPA (7.66%). In 2014–2015, cooperative banks have been permitted to invest in government bonds and securities as an alternative source of income. The sharp growth of investment (82.85% in 2014–2015 and 184.15% in 2015–2016) reveals that the bank has taken the opportunity for further income generation. Over the last decade, gross income has increased at an average of 5.40% but in 2016–2017 and 2019–2020, due to high administrative costs to maintain no-frill accounts and the unprecedented epidemic broke out of COVID-19, significant negative growth has emerged as −2.92% and −9.7%, respectively. Implementation of information communication technology has drastically reduced the gross expenditure since 2016–2017. The bank has been suffering from fluctuations in profit due to the high seasonality of the agriculture sector but a new investment opportunity in government bonds has raised the profit to its peak in 2018–2019. Thereafter, profit has again fallen due to the harsh effects of COVID-19 along with the national economic downturn. Although mean value (₹38.28 crores) of profit is much higher than the value of SD (₹14.72 crores) and high positive skewness (1.36) clearly predicts that, the financial condition of the concerned bank is highly stable, and it will also achieve a significant margin of profit in the coming years.

Table 2. Details of Financial Operations of Burdwan Co-Op Bank. (All Figures are in Crores of Rupees) Period: FY 2011–2012 to 2020–2021

Source: Prepared by the authors based on Annual Financial Reports of BCCB.

Note: SD = Standard deviation.

Discussion

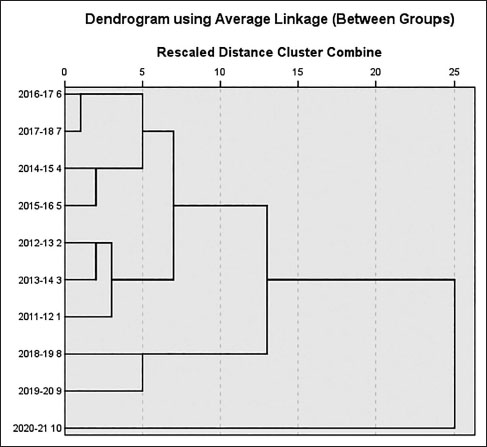

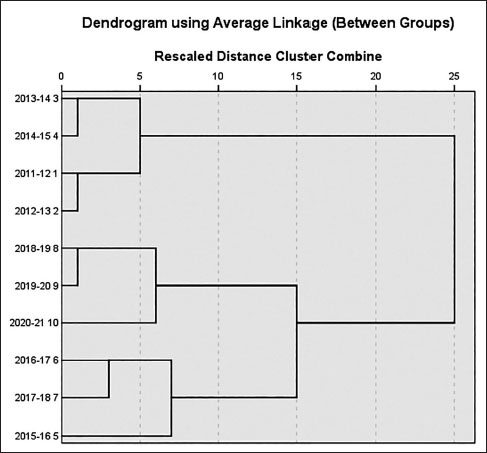

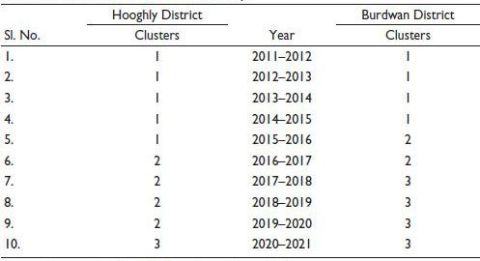

Applying the hierarchical clustering, three segments have been identified in both districts (Figure 1 and Figure 2) by observing the dendrograms in the agglomerative method with a threshold value of 5 within the 25-point scale of similarity. On the basis of the identified number of clusters, k-means clustering has been applied to obtain cluster membership of different years.

Now, final cluster membership (shown in Table 3) and their respective centres (Table 4) have finally been obtained after two iterations in the case of Hooghly district and four iterations in the case of Burdwan district by applying the k-means clustering algorithm.

Figure 1. Hooghly District Central Cooperative Bank.

Figure 2. Burdwan Central Cooperative Bank.

Source: Dendrograms by the hierarchical clustering method.

Three different segments, as shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, derived from the data incorporated in Table 4, have been affected by different characteristics, namely the introduction of PMJDY changes in cooperative banks’ policies of investment and loan disbursement, a low rate of interest in deposit accounts, demonetisation in 2016, fluctuations in agriculture loan recoupment due to climatic stress, and the effects of COVID-19.

In Table 5, mutual exclusiveness and the mutual distance between obtained clusters are presented based on k-means clustering.

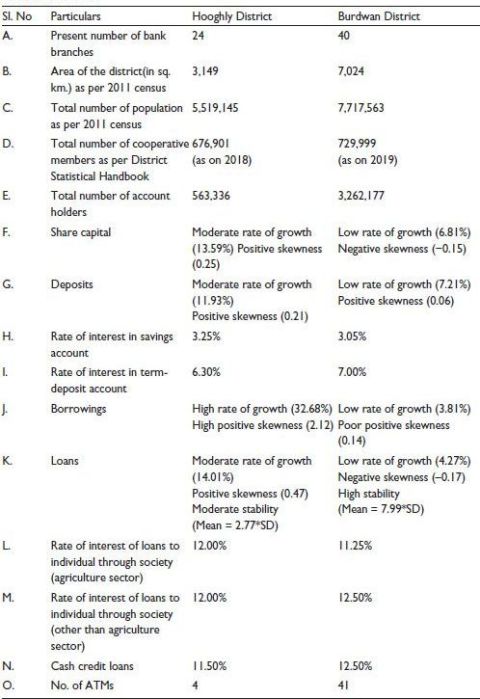

As shown in Table 6, the jurisdiction of each branch in HDCCB is 131 km2 (approx.), and it is 171 km2 in the case of BCCB. It has been estimated that a single branch of HDCCB may have an average of 23,472 deposit accounts. On the contrary, it is approximately 81,554 in BCCB. Again, it has been appraised that 12.26% of the total population of the Hooghly district are registered cooperative members of HDCCB, and it is 9.46% in BCCB. HDCCB has been performing much better in the process of inclusion of the unbanked population than its counterpart in Burdwan. Disbursement of primary school teachers’ salary through cooperative banks may be considered a high rate of growth in the share capital of HDCCB. On the contrary, BCCB has faced a lower rate of growth in share capital due to the low rate of interest offered on deposits after 2016.

Table 3. Obtained Final Cluster Membership.

Source: k-means clustering with the agglomerative method.

Table 4. Final Cluster Centres of Co-Op Banks’ Financial Operations.

Source: k-means clustering.

Table 5. Distance Between Final Cluster Centres.

Source: k-means clustering.

Table 6. A Comparative Statement of Banking Operations in Two Districts. Period: As of 31 March 2023

There is also a significant difference in the rate of interest under various deposit schemes offered by the banks. It is special to mention that implementation of interest subvention schemes could have been a cause for such a huge increase in demand for loans. But the introduction of policy changes in loan disbursement to control the higher scale of NPA by BCCB was possibly a prime reason for the reduction of loan applications. Negative skewness values of loans and borrowings are clear indications of such changes. There is also a significant difference in the rate of interest on loans between the agriculture sector and the non-agriculture sector in Burdwan. The rate of interest on cash credit loans is also high in Burdwan district, and that negatively affects the non-agricultural loan borrowers. On the contrary, the HDCCB’s policy on cash credit loans is helping the beneficiaries to alleviate their poverty status. As a result, there has been a negative impact among the grass-roots-level cooperative branches to borrow loans. However, in the case of ATM services, the BCCB has performed much better than the HDCCB and the numbers of ATM counters are also higher than the HDCCB.

The PMJDY was formulated with six prime objectives—universal access to banking facilities, providing basic bank accounts with overdraft facilities, a financial literacy programme, the creation of a credit guarantee fund, micro-insurance and an unorganised sector pension scheme to provide financial security to the unbanked population of India (PMJDY, 2014). The increment in the number of savings accounts is another indication of financial inclusion, and Table 7 represents the decadal growth of the number of savings accounts with a year-wise breakdown in both districts.

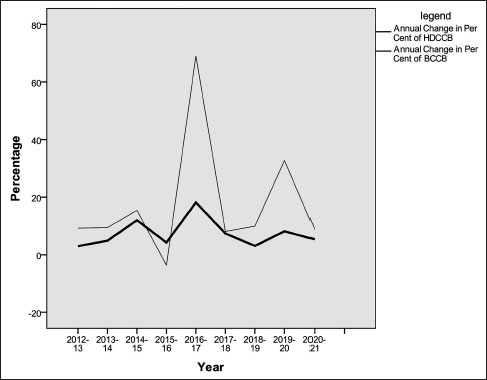

It is identified that a negative change (–3.63%) in growth of savings accounts occurred in HDCCB during 2015–2016, but the implementation of PMJDY has boosted the growth rate up to 69% in the following year. The highest positive changes (69.03% and 32.75%) in growth have been observed during 2016–2017 and 2019–2020, respectively. However, the BCCB had the highest growth (18.14%) in savings accounts during 2016–2017 due to the effective implementation of the PMJDY. Later, however, the growth rate of savings accounts was decreased due to the adverse effects of demonetisation. Percentage changes of savings accounts of both banks over the decade have been depicted in Figure 3. It is clear that HDCCB is a better performer than its counterpart just after the enactment of the PMJDY. On the contrary, the BCCB has been performing well with steady growth over the decade.

Initiatives on Community Sensitisation

The District Cell of Cooperative Union and the District Cell of NABARD have long been collaborating to organise community awareness camps, mainly at countrysides, on a regular basis. Since inception, these camps have been engaged in sensitising PACS and SHG members on the various benefits and prospects of the cooperative system. However, local people are also permitted to participate voluntarily in these camps. Bank officials have regularly been discharging their duties as co-facilitators in these awareness camps. Also, different insurance schemes as available for eligible beneficiaries on health, human life and crops are earmarked by the facilitators, and they explain the benefits of each of the schemes to those beneficiaries. An amount of Rs. 5,000 per awareness camp has been disbursed by both banks as financial support in compliance with the order of NABARD. Every year, a cooperative week has been observed between 14 November and 20 November with the support of West Bengal State Cooperative Union to discuss various areas of operations, such as cooperative marketing, strengthening health care facilities, entrepreneurship development, inclusion of youth, women and weaker sections, digitisation of PACS, inclusive development with a public-private partnership (PPP) model, cooperative training and education with the objective of developing the social capital in the long run, where the epicentre lies on financial inclusion.

Table 7. Cumulative Growth of Savings Accounts. Period: Between FY 2011–2012 and 2020–2021

Source: Prepared by the authors based on Financial Reports of the banks.

Figure 3. Annual Changes of Savings Accounts in Two District Central Co-Op Banks.

Source: Depicted as per the data in Table 7.

Conclusion

The present study sheds light on the role of Hooghly District Central Cooperative Bank and Burdwan Central Cooperative Bank as financial facilitators in the districts of Hooghly and Burdwan, respectively. Analysis of the longitudinal data of both banks has revealed positive growth of financial operations and propagation of the number of savings accounts; these are significant evidences of the inclusion of the unbanked population in the formal microfinance structure. It has been observed that changes in policy of loan disbursement, reduction in rate of interest in savings accounts, loss of agricultural production due to climatic stresses, along with the national economic downturn due to the COVID-19 situation, are among the reasons for the fluctuations in gross profit and creating potential challenges towards the financial stability of banks.

The analysis depicts that though the BCCB has much better financial stability than the HDCCB, its overall banking operations are inferior to the latter. Three significant segments have been identified out of the decadal growth of business by application of cluster analysis (Figure 1 and Figure 2). However, cluster memberships of financial years are different due to the introduction of new scheme, changes in banking policies and the sudden outbreak of epidemic diseases. The duration of the first cluster in both banks (2011–2016 in HDCCB and 2011–2015 in BCCB) was the pre-enactment period of PMJDY and the main characteristic of this segment was due to the huge loss in agricultural production affected by climatic changes. The implementation of PMJDY and changes in investment policies of cooperative banks are pointed out as the basis of generation of the second cluster (2016–2020 in HDCCB and 2015–2017 in BCCB). Finally, in the case of HDCCB, the third cluster is based on the damaging effects of COVID-19 in business operations for 2020–2021; it is, however, based on changes in loan disbursement policy, seasonality in crop yielding and adverse effects of COVID-19 for BCCB (2017–2021). It has been identified from the cumulative number of savings accounts that the performance of BCCB is more or less stable over years; however, the HDCCB’s performance over years is highly fluctuating with respect to opening of savings accounts for reasons as identified above.

Both BCCB and HDCCB have seriously implemented schemes, such as interest subvention, insurance of the Government of West Bengal and the Government of India to provide social support and financial securities to the beneficiaries. These initiatives, along with cooperative awareness programmes, have positively contributed to sustaining the growth of business for both banks.

However, some major challenges have been identified as being faced by the HDCCB—slow growth in the establishment of new branches and ATM counters across the district, a higher rate of interest on loans in the agriculture sector, a decrease in the number of savings accounts and also unexpected fluctuations in the annual growth rate of savings accounts. Again, the BCCB has been facing the following challenges:

1. probable loss may occur in the near future due to the negative value of skewness in share capital, reserve fund, loan disbursement and gross income;

2. high rate of interest in the non-agriculture sector and cash credit loans;

3. low percentage of loan recovery and higher NPA;

4. almost flat curvature of annual growth in savings accounts.

Apart from the challenges mentioned above, a moderate to high growth rate of share capital, a reserve fund, loan disbursement, a higher rate of interest in savings accounts, a lower rate of interest in non-agriculture loan, a cash credit loan and a higher annual change (in percent) in the number of savings accounts are the potential strengths of HDCCB. On the other hand, the major strengths of BCCB are the higher number of savings accounts, the higher rate of interest in term-deposit accounts, the low rate of interest in agriculture loans and the sufficient number of ATM counters operating across the district.

Considering the challenges faced by the banks, the following suggestive measures need to be explored and implemented by the banks for the betterment of banking operations in view of their role in financial inclusions:

Banks should conduct community sensitisation programmes throughout the year to attract existing and potential customers.

Banks should have to implement business correspondents and business facilitators schemes as per the RBI guidelines to percolate financial inclusion at the grassroot level.

A robust mobile application needs to be developed for a hassle-free online payment method targeting the new Gen population.

Banking hours should be flexible and customised to make banking operations more convenient to the customers.

Efforts are to be initiated, particularly in the case of HDCCB, to open more ATM counters across the district for easy accessibility of cash transactions; if possible, ATM counters may also be opened in other districts as well.

Finally, it can be stated that both the banks have stable business conditions; financial reports depict their impressive performances as financial facilitators to percolate financial inclusion in various strata of the unbanked population. Implementation of the PMJDY has escalated the praxis of Public Good theory for financial inclusion by the governing authority. The effectiveness of the said programme has significantly changed the pattern of financial inclusion by the HDCCB as depicted in Figure 3; however, the said programme has not been that much effective in the case of the BCCB.

Limitations of the Study

The present study has been undertaken to investigate the status of financial inclusion of Hooghly and Burdwan district populace as initiated by HDCCB and BCCB, respectively, and the study period is the second decade of the 21st century. Had the study been conducted across more other districts in West Bengal for a span of the last 20 years, the results would have been more effective in decision-making. The study has been limited to the state of West Bengal; had the experience of the other states been incorporated, needless to mention that the study would generate more appropriate results.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the anonymous referees of the IMIB Journal of Innovation and Management for their extremely useful suggestions to improve the quality of the paper. Usual disclaimers apply.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Notes

1. Per capita income, good governance and access to formal financial credit in a regulatory environment are considered the major financial development indices.

2. It is one of the merits of Public Good theory as referred to in Ozili (2020).

3. The Montague-Chelmsford Reforms (1919) introduced the present three-tier cooperative model; that is, primary cooperative societies at grass-roots level, district central cooperative banks at district level and state cooperative banks at state level.

4. The Maclagan Committee (1915), headed by Sir Edward Maclagan, observed that illiteracy, misappropriate usage of funds, nepotism and inordinate delay in granting loans were major hindrances of microfinance.

5. The Governor of the Reserve Bank of India had appointed Shri A.D. Gorwala as the Chairperson of the All India Rural Credit Survey Committee (1954) to produce a detailed report on demands of the credit market and future prospects of cooperatives as vehicles of rural development.

6. Presently, the West Bengal State Cooperative Bank Ltd. has been regulated under the purview of the West Bengal Cooperative Societies Act, 2006.

7. The Burdwan district was bifurcated into two districts—East Burdwan and West Burdwan—with effect from 7 April 2017, but the Burdwan Central Cooperative Bank is still operating with 40 branches spread over both districts.

8. As per the Master Circular of 1 July 2009 issued by RBI for the purpose of risk categorisation, individuals and entities whose identities and sources of wealth can be easily identified and transactions in whose accounts, by and large, conform to the known profile may be categorised as low risk.

ORCID iD

Udaybhanu Bhattacharyya  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8994-925X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8994-925X

Ananth, S., & Sabri-Oncu, T. (2013). Challenges to financial inclusion in India: A case of Andhra Pradesh. Economic & Political Weekly, 48(7), 77–83.

Beck, T., Levine, R., & Loayza, N. (2000). Finance and the sources of growth. Journal of Financial Economics, 58(1), 261–300.

Clarke, G., Xu, C., & Zou, H. (2006). Finance and inequality: What do the data tell us? Southern Economic Journal, 72(3), 578–96.

Collins, D., Morduch, J., Rutherford, S., & Ruthven, O. (2009). Portfolios of the poor: How the world’s poor live on $2 a day. Princeton University Press.

Demirguc-Kunt, A., & Klapper, L. (2012). Measuring financial inclusion: The Global Findex database [Policy Research Working Paper 6025]. World Bank.

Demirguc-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., & Van Oudheusden, P. (2015). The Global Findex database 2014: Measuring financial inclusion around the world [World Bank Group Policy Research Working Paper 7255]. World Bank.

Department of Planning and Statistics. (2018). District statistical handbook Hooghly. Office of the Assistant Director, Bureau of Applied Economics and Statistics, Government of West Bengal.

Department of Planning and Statistics. (2019a). District statistical handbook Purba Bardhaman. Office of the Assistant Director, Bureau of Applied Economics and Statistics, Government of West Bengal.

Department of Planning and Statistics. (2019b). District statistical handbook Paschim Bardhaman. Office of the Assistant Director, Bureau of Applied Economics and Statistics, Government of West Bengal.

Directorate of Rice Development. (2002). Rice productivity analysis in India. Retrieved May 15, 2024, from https://drdpat.bih.nic.in/PA-Table-25-West%20Bengal.htm

Dubhashi, P. R. (2001). Revitalising cooperative rural credit: A critique of Capoor Committee’s Report. Economic & Political Weekly, 36(17), 1378–1380.

Dubey, A. K., Singh, A. K., Singh, R. K., Singh, L., Pathak, M., & Dubey, V. K. (2009). Cooperative societies for sustaining rural Livelihood: A case study. Indian Research Journal of Extension Education, 9(1), 43–46.

Governor General of India in Council. (1904). The Cooperative Credit Societies Act (X of 1904). Retrieved October 5, 2023, from https://www.indiacode.nic.in/repealed-act/repealed_act_documents/A1904-10.pdf

Government of India. (2008). Report of the committee on financial inclusion. Rangarajan committee. Retrieved October 5, 2023, from https://www.findevgateway.org/sites/default/files/publications/files/mfg-en-paper-report-of-the-committee-on-financial-inclusion-jan-2008.pdf

Government of India. (2014). Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana—A national mission on financial inclusion. Department of Financial Services, Ministry of Finance. Retrieved November 30, 2023, from https://www.pmjdy.gov.in/files/E-Documents/PMJDY_BROCHURE_ENG.pdf

Kamath, M. V., & Kurian, V. (1996). Milkman from Anand—The story of Verghese Kurian. Konark Publishers.

King, R. G., & Levine, R. (1993). Finance and growth: Schumpeter might be right. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(3), 717–737.

Lakshmi, &Manoj, P. K. (2015). Cooperative banks and rural credit for inclusive growth: A study of Kannur district Cooperative Bank in Kerala. Indian Journal of Retailing and Rural Business Perspectives, 4(1), 1442–1450.

Majumder, C., & Gupta, G. (2013). Financial inclusion in Hooghly. Economic & Political Weekly, 48(21), 55–60.

Mitra, A. (2012, August). Cooperative bank turning to private: A case study on Saraswat Cooperative Bank. The Management Accountant, 944–946. https://icmai.in/Knowledge-Bank/upload/case-study/2012/Co-operative-Bank.pdf

Mishra, A., Vangaveti, A., & Majoo, S. M. K. (2024). Fintech reshaping the financial ecology: The growing trends and regulatory framework. IMIB Journal of Innovation and Management, 2(1), 34–44.

Mohapatra, N. P. (2016). This is financial inclusion. Economic & Political Weekly, 51(35), 4.

Mukhopadhyay, J. P. (2016). Financial inclusion in India: A demand side approach. Economic & Political Weekly, 51(49), 46–54.

Nagaraj, K. V. (2015). A case study on banking operations in cooperative sector with reference to Visakhapatnam District Cooperative Bank, Visakhapatnam. Paripex—Indian Journal of Research, 4(8), 189–192.

National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD). (n.d.). Genesis and vision. Retrieved on May 1, 2023, from https://www.nabard.org/content.aspx?id=2

Ozili, P. K. (2020). Theories of financial inclusion. In E. Ozen & S. Grima (Eds.), Uncertainty and challenges in contemporary economic behaviour (pp. 89–115). Emerald Publishing Ltd.

Rao, S. (2007). Financial inclusion: An introspection. Economic & Political Weekly, 42(5), 355–360.

Reserve Bank of India (RBI). (n.d.). About us. Retrieved October 5, 2023, from https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/AboutUsDisplay.aspx?pg=StateCooperativeBanks.htm

Roy, D. (1982). Reorganisation of rural credit in West Bengal through the cooperative institutions during the plan period. West Bengal State Cooperative Union.

Senapati, A. K., & Parida, D. (2024). Labour force participation, gender equity and women’s empowerment through micro-entrepreneurship: Evidence from Odisha, India. IMIB Journal of Innovation and Management, 2(1), 82–99.

Teki, S., & Mishra, R. K. (2012). Microfinance and financial inclusion. Academic Foundation.

The West Bengal State Co-Op Bank (WBSCB). (n.d.). Genesis mission. Retrieved on October 1, 2023, from https://www.wbstcb.com/page/genesis_mission