1 School of International Business and Entrepreneurship (SIBE), Herrenberg, Germany

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

Power and influence are important factors and are closely linked to leadership and our acceptance of it. However, in the relatively recent systematic examination of these phenomena and their emergence and implementation, at least some facets remain underexamined. The focus is primarily on psychological incentive systems. In our article, we want to argue that this form of consideration is important, but not sufficient and sometimes even remains one-sided. This is due to the restriction of the incentive systems themselves, which primarily change the consequences of actions for the guided one or are related to the guided person’s lack of access to knowledge, for example. We, therefore, want to argue in favour of an extension of the theory and clarify as a core thesis why the power and influence of leadership also go hand in hand with the simplification of collective actions, fairness and cooperation. We want to realise this project at all levels on the basis of arguments from action theory (primarily decision and game theory).

Coordination, decision theory, game theory, conflict avoidance, fairness, cooperation

Introduction

Power and influence are factors that have always been seen as somehow desirable in our society. However, in addition to the eternal desire of some to gain influence and have power, both factors are essential, especially with regard to a management task or leadership.i Both—exercising certain forms of power and having influence—are implicit social requirements of a broad catalogue of tasks in leadership and management. This concerns not only the concrete assertion of something (e.g., by an employee) but also a far-reaching facet of interpersonal or social behaviour. This social aspect demands specific characteristics from managers, all of which seem to be in a field of tension: it is expected that you motivate employees or those you lead, but that you never lose your assertiveness in the process. You should act correctly and ethically but never lose sight of the criteria of efficiency. You should remain fair while radiating confidence, security and commitment.ii The list seems long and illustrates how complex the social areas affected by leadership and its power and sphere of influence are. Even if the practical examination of the phenomenon of power and influence is probably much older, the first attempts to systematise it in the field of leadership are a fairly recent development. Psychological theories for categorising and understanding power and influence are becoming increasingly popular, particularly in the field of management, and courses for learning about them are enjoying great popularity.ii

However, the existing approaches often remain on a purely psychological descriptive level or even become a form of psychological sleight of hand that illustrates how to read and control those being guided.iv In this article, we will attempt to broaden our view of the power and influence of leadership. This does not mean that psychological approaches are obsolete or even to be criticised in their entirety. Rather, the perspective on power and influence in leadership will be supplemented by specific systematic endeavours. The literature review (Chapter 4) will therefore provide an overview of prevailing theories of power and influence. We will then show what our objectives are (Chapter 5) in our examination of power and influence and present the theoretical basis of our argument (Chapter 6). For the methodological basis, we will then take a look at game and decision theory itself (Chapter 7), in order to clarify which gaps power and influence can fill through leadership (Chapter 8). This is followed by a discussion (Chapter 9), the conclusion (Chapter 10) and the implications for leadership and management (Chapter 11). Below are the imitations (Chapter 12) of the work, which also emphasise once again that our article is a theoretical-philosophical argument and not a conclusive empirical study.

Review of Literature: The Orthodox View of Power and Influence

In order to be able to understand and possibly expand on power and influence, it seems sensible to take a look at classical approaches as a first step. The relatively recent debate is already characterised by a wealth of theories and approaches, including the examination of social systems,v communication in the mediavi and the discussion in various areas.vii Since the entire variety of approaches and theories are too broad, we will limit ourselves here to better understanding the general thrust of these theories.viii In general, Dahl (1957, p. 202), for example, understands power as follows: ‘My intuitive idea of power is something like this: A has power over B to do not something what B would otherwise do’. Influence, on the other hand, can be understood as the change in opinions, attitudes or behaviour through the influence of others.ix

One of the best-known theories on the development of power and influence, by French and Raven (1959), can now be considered as an example. This approach still describes an important foundation with far-reaching influence today. According to French and Raven (1959), the focus is on the assumption that power represents a didactic relation between agents, which can be viewed from different angles. Accordingly, power and influence are described by a person P and his individual view. Power and influence are exerted from person O on person P. Influence and power are generally defined in terms of psychological changes that are triggered by this and are assumed to be two components that act on a system. Whereby the system (a) can be changed in a desired direction and (b) can generate appropriate resilience. The theory itself focuses on the changes within an observed system, while all other social factors and conditions are assumed to be constant. Along these assumptions, French and Raven (1959) postulate five observable forms of power that can influence each other, but are based on different systemic hypotheses:

In this context influence also arises through the development of power. Schematisation describes important relationships and it is not without reason that it continues to be of central importance today. Nevertheless, the general argumentation is partially one-sided if one considers leadership and the required catalogue of characteristics in their entirety. Because leadership, when exercised appropriately, requires power and influence.x The forms of power described can be subsumed under various formulations of incentives or sanctions (also in the motivational sense). This can be indirectly compared with corresponding incentive systems in decision and game theory. Here, for example, the preferences of an actor can be (subsequently) changed by penalties or incentives as described above.xi For example, actor A might prefer to go on holiday by plane rather than by car or train (A has the following preference order: A > B > C). If travelling by plane were associated with corresponding sanctionsxii (by a person who wants to exercise power) this can shift the preferences accordingly to: B > A > C and actor A would then decide to go on holiday by car. On this basis, such incentive and punishment systems are often utilitarian or consequentialist in nature and entail some pitfalls.xiii

This is the case because the actor’s evaluation level is changed, which relates exclusively to the consequences of his action. However, if the actor has a different motivational basis that determines or co-determines his action, such incentive systems need not influence or change his preferences. In such a case, French and Raven’s (1959) power and influence do not necessarily lead to power and at least do not cover all possible forms of power. Furthermore, empirical data show that changing the preferences of actors via, for example, sanction or incentive systems can often lead to so-called micro-sabotage.xiv If the management does not take such factors into account, this can lead to the wrong undesirable results in the long term and suggest power and influence, but not generate them in a stabile manner. Such forms of power and influence in hierarchical form can also lead to certain exploitative structures.xv At the very least, it can be summarised that such a theoretical approach is very important, but cannot be conclusive.

Objectives

The two main theses and goals are the following: First, it should be made clear that it seems sensible to broaden the perspective on power and influence (in an interdisciplinary way), as existing contributions do not reflect the entire wealth of these phenomena in the field of leadership.xvi Second, an attempt will be made to look at power and influence from the perspective of collective action (or game theory). The focus is on the latter. The argumentation aims to illustrate that power and influence are helpful on a fundamental level to ensure a quick and easy decision-making process in collective decision-making situations. The argumentative approach of the article is limited to discussions of (rational) decisions. This means that mainly arguments and examples from game theory, decision theory and collective action are used. The argumentation is purely theoretical and philosophical and not statistical. This is intended to broaden the facets of the phenomena of power and influence in the field of leadership with a corresponding, additional perspective.

Theoretical Frameworks: Leadership as Solution for Collective Action

Instead of focusing on individual incentive systems, there are approaches in decision and game theory that concentrate on and help us understand collective actions.xvii There are many different discussions and theories in this area, the complexity of which would go beyond the scope of this article.xviii At this point, it is sufficient to look at the case of simple action coordination and expand on it for the present argumentation of the perspective of power and influence among leaders.xix The focus shifts from incentive systems that are already based on fixed motivations for action (e.g., avoidance of punishment) on the part of the person in charge to open systems of action.xx In the first step, the argument aims to show that leadership functions as a simple solution for collective action and can thus generate power and influence. King et al. (2009, p. 914) already indicated the central importance of leadership as a simple solution strategy in collective action situations. Similar remarks can also be found in Harsanyi (1962, p. 82), because ‘[p]ower relations became relevant in social groups when two or more individuals have conflicting preferences and decision has to be made as those to whose preferences shall prevail’.

Coordination between actors now also applies to game theory, in which actors choose their actions according to their preferences given the actions (and preferences) of others. So-called equilibria are decisive here, in which players cannot improve their actions by choosing a different strategy.xxi Strategic combinations are considered Pareto-optimal if none of the players can improve without making another worse off.xxii In interaction situations, there can now be various coordination problems between the actors involved. Lewis (1969) describes this in the example of an interrupted call. Two actors A and B are having a telephone conversation and this is suddenly interrupted. Both actor A and B can now either try to call the other again or wait for the other to call again. If both call again at the same time, the call is not made (busy). If neither of them calls the other again, the call cannot be continued. The two have no opportunity to coordinate, which leads to the following preference matrix with two equilibria (marked bold).xxiii

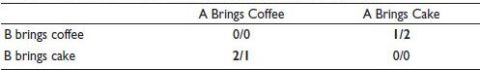

Furthermore, coordination can take place under conflict if actor A and B want to meet for a café and cake, for example, and agree that one will bring cake and one will bring café, whereby both prefer to bring café, as this is less work. We still get two equilibria.

In both cases, this is sometimes an epistemic problem that can be resolved to a certain extent through agreements or conventions.xxiv Often, however, no real agreements are possible or conventions predetermined, and these problems are exacerbated by the growing number of players involved.xxv Let us extend the first example and assume an interrupted online conference or a group telephone call consisting of a number n of participants who all have to coordinate their actions as described. In most cases, the problem with real online conferences with a large number of participants does not arise in individual action decisions, conventions or even individual agreements among all participants. Rather, there is an implicit agreement that one of the participating players will take the ‘lead’ over the online channel and conference access. In this extended sense, leadership can describe a simple solution for collective actions, which becomes more important as the number of participants in collective actions increases. The agreement does not require a permanent exchange between all participants, but it is sufficient to know that the person in question is acting in the interests of everyone in order to avoid problems in this regard as far as possible. The coordination of all persons n involved is bundled via the knowledge and agreement of all that one person from n will coordinate this accordingly. In the event of conflict (example two), the premise is added that this person not only acts in the interests of all, but also does so as fairly as possible (especially in the long term). Through this acceptance, the leading person gains power and influence (e.g., via online access to the conference), subject to corresponding additional structures and responsibilities. The determination of an equilibrium between the actors is sufficient to exert power and influence and does not have to be contrary to the original preferences of the actors. This is particularly important when coordination is viewed in terms of conflict or cooperation.

Table 1. Simple Coordination (see e.g., Lewis, 1969, p.12).

.jpg/10_1177_ijim_241274390-table1(1)__480x70.jpg)

Table 2. Coordination with Conflict (see e.g., Schelling, 1960, p.126).

Methodology

The methodology of game and decision theory itself, as well as its philosophical analysis in a normative context, is fundamental to the consideration and argument in favour of leadership from the perspective of collective action. The formal conditions are considered on the basis of the properties of binary relations. X is a non-empty, finite set whose elements are the alternatives x, y, z etc. that are to be decided upon (X = {x, y, z, ...}). The alternatives are mutually exclusive. The following relations between the elements x and y of a set of alternatives are relevant at this point:

,

,.png) xxvi

xxviThen u is a function of x according to .png) , which maps the preference relation R to ordinal values, so that

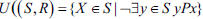

, which maps the preference relation R to ordinal values, so that .png/image(54)__135x16.png) exactly when R is complete and transitive and the corresponding person maximises her utility along with her preferences. This can be described by the following selection function U, which selects the alternative(s) from the set

exactly when R is complete and transitive and the corresponding person maximises her utility along with her preferences. This can be described by the following selection function U, which selects the alternative(s) from the set .png) for which no better alternative exists in S:

for which no better alternative exists in S:

xxvii

xxvii

The formal conditions can also be used or extended for an analysis under probabilities. This means that decisions can also be modelled under uncertainty.xxviii Game theory builds on decision theory by extending it to interactions between two or more people. The classical understanding of the game indirectly includes the intention of each player to achieve the best possible outcomes according to their preferences—always given the actions of the other players. The normal form of a game is represented as a triple (I, S, U) as follows:

Here .png) denotes the set of players and

denotes the set of players and .png) the set of strategies (possible actions) of the players i. The strategy space S specifies the set of all possible strategy combinations s = (s1, s2,..., sn) from the strategies of the individual players, that is, s

the set of strategies (possible actions) of the players i. The strategy space S specifies the set of all possible strategy combinations s = (s1, s2,..., sn) from the strategies of the individual players, that is, s S. Here, Ui(s) reflects the utility of player i when a strategy combination i is played (utility function U= (U1,..., Un)). If a certain strategy combination s is played in a game, this results in the benefit combination U(s).xxix A strategies si

S. Here, Ui(s) reflects the utility of player i when a strategy combination i is played (utility function U= (U1,..., Un)). If a certain strategy combination s is played in a game, this results in the benefit combination U(s).xxix A strategies si S is dominant for i

S is dominant for i  I, if and only if

I, if and only if .png) And weakly dominant when

And weakly dominant when .png) A strategy profile s*

A strategy profile s* .png) S is an equilibrium point (Nash equilibrium) if

S is an equilibrium point (Nash equilibrium) if .png) .

.

Analysis: Power and Influence Through Coordination and Conflict Reduction

So far, it has been explained how classical approaches usually do not reflect all forms of power and influence and attempts have been made to show that leadership can primarily simplify collective actions, which indirectly entails power and influence. In the following, the previous argumentation will be put into a corresponding form and further supported by arguments. But how can power and influence be generated from this attribution of leadership itself? First, it is helpful to clarify more precisely how leadership simplifies actions in the collective case. Let us return to the example of the online conference, in which leadership facilitates general coordination (without conflict). This ‘facilitation’ is achieved by the fact that no agreement between all participants or conventional regulation of online access needs to be created. The fact that everyone (group g) wants to participate in the online conference appears to be an (implicit or explicit) collective goal u(g), which can be achieved more quickly and easily by leadership. Provided that it represents this common goal in the interests of all (and their preferences) or even generates this goal in the first place (e.g., through a conference invitation or the idea for the online conference). Power and influence then do not arise through specific access, rewards or sanctions in the form of subsequent changes to the consequences (and thus possibly the preferences) of those involved, but through the epistemic simplification of the situation for all actors in order to achieve u(g). In this case, power is not opposed to the original preferences of the actors, but is associated with a clear definition and possibility of organisation. Accordingly, these are specific forms of power and influence.xxx

In the simpler two-person case of the telephone call, there are two equivalent equilibria (1/1) between the actors, which only need to be coordinated to an arbitrary equilibrium. Leadership coordinates a group g in such a way that a common goal u(g) can be achieved as far as possible in line with the preferences of each individual group member without individual agreement between all of them or generates u(g) in the first place. The group g then accepts this goal/coordination through the attribution of power and influence. The attribution of power and influence takes place through the simpler achievement of a common goal and arises with the confidence to realise this accordingly. In cases of conflict (café cake example), this coordination towards a common goal u(g) of a group g of n participants becomes even more difficult. However, this is not related to more difficult coordination between the participants, but to the question of the common goal. Even in the simple two-person example, there are two equilibria that need to be coordinated. However, these are unequally valued by the participants. One of the participants has to draw the short straw here and bring the cake with additional effort so that an equilibrium can be achieved at all and the common goal of meeting for a café and cake can be realised (otherwise everyone’s preferences will be worse off). In situations involving a larger group g, this imbalance can become even more complicated. When coordinating a common goal u(g) in the interests of the group and the individual preferences of the participants, fairness must be ensured in the long term so that the interests of all participants are given equal consideration.

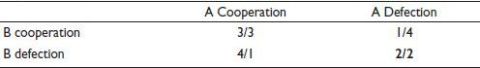

In the two-person case, this could mean that if player A brings a café the first time, the next time they have to take care of the cake (or other additional work). In a group g with n participants, leadership not only simplifies coordination, but also fairness in the long term towards achieving a common goal u(g). This is necessary so that everyone participates in a common goal in the long term, because anyone who is treated unfairly will distance themselves from it.xxxi To achieve this fairness, individual group members must be prepared to sacrifice their own preferences (bring cake) due to the power of the leadership. The attribution of power and influence to leadership is supplemented here by other factors that affect fairness in the interests of all and thus ensure the achievement of a common goal between them. Finally, the more complex case of cooperation should be mentioned here. Cooperation is therefore more complex, as in a two-person case both actors have to distance themselves from their own preferences in order to achieve a better result together (cf. prisoner’s dilemma).xxxii Leadership and the acceptance of the collective goal of the participants can generate cooperation here (which is better for everyone in the long run), whereby the equilibria of the original game can be found as follows:

This will not be explained further here, as it would lead to a very broad general discussion. However, it should be pointed out at this point that leadership also simplifies cooperation in the sense mentioned. Cooperation can only come about if none of the actors involved exploits the other’s willingness to cooperate in the interests of their own preferences (free riders). Here, leadership can not only have a helpful coordinating effect (epistemic mediation), but can also identify free riders in the interests of all and, for example, punish them, create appropriate conditions and thus ensure the achievement of the common goal u(g)—which in this case would be the cooperative solution—in the long term. Power and influence would then be ascribed through the attribution of the guarantee of cooperation, which involves individuals stepping back from their original preferences (defection). In conclusion, it can now be summarised that leadership in the following cases is granted and attributed power and influence by a group g:

1. For the possible generation of a common goal u(g).

2. To coordinate a common goal u(g).

3. To ensure fairness in reaching u(g).

4. To maintain cooperation in the sense of u(g).

Power and influence is ceded to leadership in order to achieve the collective goal more easily and to reduce conflicts. The power and influence of a leader grow with good coordination, fairness, cooperation and, for example, other appropriate punishment in the event of deviation in the interests of all.xxxiii

Discussion

The argument of the perspective of power and influence in leadership is limited to collective decisions in the game theory case. The formal representation of collective choice has been disregarded here and not considered in detail.xxxiv The psychological perspective is also not taken any further, as this has been sufficiently analysed in the literature. Similarly, the argument is not that cooperation and coordination along the preferences of actors or a group cannot come about by themselves, but that leadership extremely simplifies and facilitates both cases by attributing each participant. This may be an obvious factor, but one that is ignored in any consideration of power and influence. The analysis here is focussed on the two-way relationship between leader and follower and what added value power and influence can generate from leadership.

Conclusion

In the argumentation presented above, an attempt has been made to show that although classic approaches to power and influence are important tools and theories, they do not represent all the basic outlines of the phenomena. Accordingly, we tried to expand power and influence in terms of the attribution of leadership to include an additional perspective that seems fundamental. It was argued that the attribution of power and influence in leadership goes hand in hand with the simplification of coordination, fairness and the maintenance of cooperation. Or even create and generate a common goal in the first place. A group ascribes power and influence to a leader—in the sense of imposing punishments for deviations or distributing tasks—in order to better achieve common goals. If leadership is coordinatively simplifying, fair and focused on the functioning of joint cooperation, it is able to assert power and influence in the long term. Otherwise, power and influence will be denied (see also micro-sabotage). This is the case, for example, if one or more players feel unfairly treated in the group in the long term, because then the influence decreases and the power of a person is questioned accordingly.xxxv This does not seem to replace classical psychological approaches in any way, but it is another aspect if we want to understand power and influence in leadership in its entirety. At the very least, this requires further discussion.

Table 3. Prisoner`s Dilemma (see e.g., Nida-Rümelin, 2019, p. 63).

Managerial implications

The implications for management theory and practice can be read directly from the results. Power and influence are crucial for achieving and advancing goals in an organisation. This shows that previous approaches to power and influence are limited, usually only effective in the short term and can even lead to losses for the organisation itself and the manager in the long term. Accordingly, the results that make it clear that power and influence go hand in hand with the coordination and cooperation of collective preferences of those involved appear to us to be crucial. Power and influence are generated here on the basis of a simple epidemic gap, as well as extended by fairness relationships and the regulation of the group in the interests of all. Good leadership therefore requires much more than psychological means to generate power and influence, but must always have the goals of all those involved in an organisation in mind. Based on the argument presented, power and influence and leadership or management positions in organisations can therefore be gained in the long term through:

1. The generation of common goals (new goals)—especially through (disruptive) innovations that create them.xxxvi

2. The coordination of this in the sense of a goal accepted by all (given their preferences in the long term).

3. Compliance with fairness in coordination and constant, transparent communication of the procedure here (conflict avoidance).

4. Generate cooperation between all to achieve the common goal (even if this means favouring a common consensus over the participants’ own preferences—structurally advantageous in the long term).

Limitations

Unfortunately, some questions must remain unanswered at this point. For example, the question arises in detail of how an individual actor generates the preferences in a group towards a common goal in the first place and when this is successful and when not. Beyond simplified systems, the question must also be asked how humans understand fairness in detail and what we rationally perceive as fair or unfair.xxxvii When is power recognised in this context? The extended discussion of cooperation also remained very limited at this point for reasons of space. It remains questionable how leadership can contribute in detail to cooperative goals, their generation and realisation and how it can better contribute to their maintenance. There are certainly a number of factors here that have been overlooked up to now and help to develop a better understanding of power and influence in this context. Questions include, for example, when we do or do not accept means to enforce cooperation towards a common goal. We also need to take a closer look at our general understanding of leadership and its definition.xxxviii It also remains to be seen how psychological approaches can be adequately integrated here. The application at this point is feasible and quite interesting. It shows which forms of punishing power, for example, are accepted by followers and when they lead to micro-sabotage and loss of trust instead. The results are closely linked to the results presented here and need to be expanded accordingly. The argument is also based on a philosophical level and requires an extended empirical-statistical examination. Regardless of the many unresolved questions and problems, as well as the possible transfer to concrete leadership situations in practice, we hope to be able to show that the phenomena play a role in a broader context and that this can contribute to an understanding in connection with leadership.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to the anonymous referees of the journal for their extremely useful suggestions to improve the quality of the article. Usual disclaimers apply.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Notes

i. Cf. Scholl (2014).

ii. HR today (2023).

iii. See, for example, Harvard Business School (2013) or for newer theories, for example, Durupinar et al. (2011), Collins and Raven (1969) or Hollander (1964).

iv. Ibid.

v. Cf. Parson (1963).

vi. Ibid.

vii. Cf. Bierstedt (1950), p. 730.

viii. See further, for example, Zündorf (1987), Dahl (1957), Crott (1983) or Schneider (1977) for an overview and classification of different approaches here. Also, Henderson (1981, p. 73), for example, distinguishes only four different main groups of power conceptions. Neuberger (1985), on the other hand, divides the approaches into structural and personalised conceptions. One of the reasons for this is that the attribution of personality attributes has long been the focus of research. Further criteria of division can be found in Pollard and Mitchell (1972), who distinguishes between (a) the analysis of the means of power, (b) the focus between realised and potential power, (c) the inclusion of the situation and (d) the reaction of those affected in the theory landscape. An overview of the evaluation of the various theories of power and influence, on the other hand, can be found in Schopler (1965), while a classification in the social sciences is made by Sander (1990), for example. In the latter, the focus is on the search for regularity stemming from a social reality outside the individual.

ix. Whereby the definition always refers to social influence. Cf. Dorsch Lexikon der Psychologie (2023).

x. Cf. Homann und Suchanek (2005).

xi. Or the epistemic access to states of knowledge or positions that an actor does not possess himself, but another does.

xii. This sanctioning can, but does not have to be of a monetary nature, it is only important that it shifts the preferences and their evaluation by the actor through incentive or sanctioning systems. An alternative example would be sanctioning with a prison sentence, etc.

xiii. Moreover, utilitarian and consequentialist interpretations are much criticised in their own right at this point. See, for example, Von Kimakowitz et al. (2011) or Nida-Rümelin (1997).

xiv. See, for example, Yasir et al. (2020).

xv. See, for example, Bagchi and Sharma (2024).

xvi. This is also meant in a sense that goes beyond the argumentation presented in the text. Even if the argumentation here is limited to this and to the theory of action.

xvii. Theories of collective action themselves are also helpful here.

xviii. Some key approaches can be found in Tuomela (2007) and Nida-Rümelin (2019), among others

xix. The more complex case of cooperation is not discussed further here. However, it can be included in a correspondingly extended discussion when it comes to leadership tasks.

xx. These also offer the possibility of being interpreted in a variety of motivational or normative ways.

xxi. Cf. Kreps (1988), p. 65.

xxii. Ibid.

xxiii. The figures only reflect the assessment of the preference order. The higher the number, the higher the preference.

xxiv. Cf. Lewis (1969).

xxv. See, for example, Paternotte (2011).

xxvi. See Kern and Nida-Rümelin (1994).

xxvii. See Kern and Nida-Rümelin (1994).

xxviii. This extension is not relevant in the sense of the consideration made here and further requires the axioms of continuity and independence in order to depict the expected utility, for example, according to von Neumann and Morgenstern (1944).

xxix. The set of all permissible combinations of benefits for all s S is denoted by:

S is denoted by:

.png)

xxx. Cf., for example, the following approaches: Couzin et al. (2005), Wilson (1975) or De Waal (2005).

xxxi. On fairness and the importance of participation in collective action, see, for example, from an evolutionary perspective De Waal (2019) or Tomasello (2009).

xxxii. See, for example, Tuomela (2007, 2013) or Nida-Rümelin (2019).

xxxiii. This can also be further supported by empirical data and existing considerations from decision theory. See, for example, Camerer (2003), King et al. (2009) or Mesoudi (2008).

xxxiv. See, for example, Kern and Nida-Rümelin (1994).

xxxv. Cf. De Waal (2005).

xxxvi. This is based on the concept of innovation discussed in, among others Faix (2022).

xxxvii. So, there is a wide debate about what we think is fair and what is not. See, for example, Fenton (2021).

xxxviii. See, for example, Faix et al. (2021), Greenleaf (1998) or Haslam et al. (2005) for the different definitions of leadership. Kisgen (2017) provides an overview here and illustrates how many different theories and approaches there are in this regard.

ORCID iDs

Anna-Vanadis Faix  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7720-7574

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7720-7574

Stefanie Kisgen  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6278-6323

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6278-6323

Bagchi, S. N., & Sharma, R. (2024). Disempowered by leadership: Tales from the middle of the organizational pyramid. IMIB Journal of Innovation and Management, 2(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/ijim.241245799

Bierstedt, R. (1950). An analysis of social power. American Sociological Review, 15. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.2307/2086605

Camerer, C. F. (2003). Behavioural game theory. Experiments in strategic interaction. Princeton University Press.

Collins, B. E., & Raven, B. H. (1969). Group structure: Attraction, coalitions, communications, and power. In G. Lindzey & E. Anderson (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (Vol. IV, pp. 102–203). Addison-Wesley.

Couzin, I. D., Kruase, J., Franks, N. R., & Levin, S. A. (2005). Effective leadership and decision-making in animal groups on the move. Nature, 433. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03236

Crott, H. (1983). Macht. In D. Frey & S. Greif (Eds.), Sozialpsychologie. Ein Handbuch in Schlüsselbegriffen (pp. 231–238). Urban & Schwarzberg.

Dahl, R. A. (1957). The concept of power. Behavioural Science, 2. https://doi.org/10.1002/bs.3830020303

De Waal, F. (2005). Der Affe in uns. Warum wir sind, wie wir sind. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag.

De Waal, F. (2019). The age of empathy. Nature`s lessons for a kinder society. Souvenir Press.

Dorsch Lexikon der Psychologie. (2023). Einfluss. Retrieved December 13, 2023, from https://dorsch.hogrefe.com/stichwort/einfluss-sozialer

Durupinar, F, Pelechano, N., Allbeck, J., Güdükbay, U., & Badler, N. (2011). How the ocean personality model affects the persecution of crowds. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications, 31(3). https://doi:10.1109/MCG.2009.105

Faix, A.-V. (2022). Qualitative Innovation in the light of the normative: A minimal approach to promoting and measuring successful innovation in business. IMIB Journal of Innovation and Management, 2 (2). https://doi.org/10.1177/ijim.221091004

Faix, W. G., Kisgen, S., Schwinn, A., & Windisch, L. (2021). Führung, Persönlichkeit. Bildung. Mit Führungskraft die Zukunft erfolgreich und nachhaltig gestalten. Springer.

Fenton, B. (2021). To be fair. The ultimate guide to fairness in the 21th century. Mensch Publishing.

French, J. R. P., & Raven, B. (1959). The basis of social power. In D. Cartwright (Ed.), Studies in social power (pp. 529–569). University of Michigan Press.

Greenleaf, R. K. (1998). The power of servant leadership. Berrett-Koehöer Publisher, Inc.

Harsanyi, J. C. (1962). Measurement of social power in n-person reciprocal power situations. Journal of Science, 7. https://doi.org/10.1002/bs.3830070106

Harvard Business School. (2013). Power and influence for positive impact. Retrieved January 1, 2024, from https://account.myhbx.org/s/login/?startURL=https%3A%2F%2Faccount.myhbx.org%2F&PC=PIPI

Haslam, S. A., O`Brien, A., Jetten, J., Vormedal, K., & Penna, S. (2005). Taking the strain: Social identity, social support, and the experience of stress. British Journal of Social Psychology, 44. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466605X37468

Henderson, A. H. (1981). Social power. Social psychological models and theories. Praeger Publishers

Hollander, E. P. (1964). Leadership and power. In G. Lindzey & E. Aronson (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (Vol. II, pp. 485–537). Random House.

Homann, K., & Suchanek, A. (2005). Ökonomie: Eine Einführung. Mohr Siebeck.

HR today. (2023). Macht oder Einfluss. Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://www.hrtoday.ch/de/article/macht-oder-einfluss-leader-erreichen-ihre-ziele-durch-gekonnte-status-spiele

Kern, L., & Nida-Rümelin, J. (1994). Logik kollektiver Entscheidungen. De Gruyter Verlag.

King, A., Johnson, D. D. P., & Vugt, M. V. (2009). The origins and evolution of leadership. Current Biology, 19(19). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.027

Kisgen, S. (2017). The future of business leadership education in tertiary education for graduates. Steinbeis-Edition.

Kreps, D. M. (1988). Notes on the theory of choice. Taylor & Francis Group.

Lewis, D. K. (1969). Convention: A philosophical study. Wiley-Blackwell.

Mesoudi, A. (2008). An experimental simulation of the “copy-successful-individuals” cultural learning strategy: Adaptive landscapes, producer-scrounger dynamics, and informational access costs. Evolution and Human Behavior, 29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2008.04.005

Neuberger, O. (1985). Führung. Enke.

Nida-Rümelin, J. (1997). Economic rationality and practical reason. Springer.

Nida-Rümelin, J. (2019). Structural rationality and other essays on practical reason. Springer.

Parson, T. (1963). On the concept of influence. The Public Opinion Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1086/267148

Paternotte, C. (2011). Being realistic about common knowledge: A Lewisian approach. Synthese, 183(2). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-010-9770-y

Pollard, W. E., & Mitchell, T. R. (1972). Decision theory analysis of social power. Psychological Bulletin, 78(6), 433–446.

Sander, K. (1990). Prozesse der Macht. Zur Entstehung, Stabilisierung und Veränderung der Macht von Akteuren in Unternehmen. Springer.

Schelling, T. C. (1960). The strategy of conflict. Harvard University Press.

Schneider, H.-D. (1977). Sozialpsychologie der Machtbeziehungen. Enke.

Scholl, W. (2014). Führung und Macht: Warum Einflussnahme erfolgreicher ist. Humboldt Universität Berlin. Retrieved December 12, 2023, from https://www.artop.de/fuehrung-und-macht-warum-einflussnahme-erfolgreicher-ist/

Schopler, J. (1965). Social power. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 2, 177–218.

Tomasello, M. (2009). Why we cooperate. The MIT Press.

Tuomela, R. (2007). The philosophy of sociality. The shared point of view. Oxford University Press.

Tuomela, R. (2013). Social ontology: Collective intentionality and group agents. Oxford University Press.

Yasir, H., Asrar-ul-Haq, M., Amin, S., Noor, S., Haris-ul-Mahasbi, M., & Alsam, M. K. (2020). Corporate social responsibility and employee performance: The mediating role of employee engagement in the manufacturing sector of Pakistan. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27, 2908–2919.

Von Kimakowitz, E., Pirson, M., Dierksmeier, C., Spitzeck, H., & Amann, W. (2011). Introducing this book and humanistic management. In E. von Kimakowitz & M. Pirson (Eds.), Humanistic management in practice.

Von Neumann, J., & Morgenstern, O. (1944). Theory of games and economic behavior. Princeton Classic Editions. Princeton University Press. Palgrave Macmillan.

Zündorf, L. (1987). Macht, Einfluss und Vertrauen – Elemente einer soziologischen Theorie des Managements. Arbeitsbericht Nr. 31 des Fachbereichs Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaften.

Authors’ Bio-sketch

Anna-Vanadis Faix is a philosopher and economist. She is currently a research assistant and doctoral candidate at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. She previously studied philosophy and economics at the University of Tübingen, the University of Padova and the University of Cambridge.

Prof. Dr Stefanie Kisgen, Junior Professor of Leadership at Steinbeis University. Managing Partner of the School of International Business and Entrepreneurship GmbH (SIBE) at Steinbeis University with currently approx. 400 students in Master’s programmes in the areas of Business & Law and more than 5,000 graduates. Studied Regional Studies China at the University of Cologne and Nanjing Normal University / China (Dipl.-reg. - 2004). Career integrated postgraduate studies for a Master of Business Administration at the SIBE of Steinbeis University Berlin (MBA - 2007). Part-time doctorate (Dr. phil.) at the Ludwigs-Maximilians-Universität (LMU) Munich (2017) on the topic ‘The Future of Business Leadership Education in Tertiary Education for Graduates’.