1Department of Commerce & Business Studies, Jiwaji University, Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, India

2Department of Management, Prestige Institute of Management & Research, Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

The present research is a portrayal to examine the impact of financially independent mothers’ prior product knowledge and information search on their purchase intention of nourishment products for their children. The research is empirical in nature, and the sampling element is financially independent mothers. Mothers who are part of a couple or a family may need to consult with their partner or other family members before making a purchase, making it more difficult to understand their intentions. On the other hand, financially independent mothers have more autonomy and can make decisions more quickly and easily. Non-probability purposive sampling techniques were used to approach the target population. The findings of the present study demonstrate that prior product knowledge and information search influence the purchase intention for nutrition products in the context of financially independent mothers. The study’s implications are multifaceted and offer valuable insights for marketers, policymakers, healthcare professionals and brands targeting mothers and children in the nourishment product market.

Prior product knowledge, information search, purchase intention, health, nutrition

Introduction

Maintaining a balanced dietary intake is paramount for promoting overall well-being and optimal health. Food serves as a vital source of energy, protein, essential fats, vitamins and minerals essential for survival, growth and efficient bodily functions. Ensuring an appropriate balance of nutrients necessitates the incorporation of a diverse range of meals into our diets. This is particularly crucial for school-age children, whose bodies are undergoing rapid development, requiring essential nutrients and energy for both physical growth and cognitive learning. To meet their nutritional needs, children must consume a variety of foods from each food group. However, various factors, such as food availability at home and school, peer influence and media exposure, significantly impact children’s dietary decisions.

Poor nutrition can have detrimental effects on both the well-being and educational potential of school-age children. Optimal nutrition involves consuming three nutritious meals per day, along with two healthy snacks, while minimising the intake of high-sugar and high-fat foods. Adequate intake of fruits, vegetables, lean meats and low-fat dairy products, including calcium-rich foods like milk, cheese or yogurt, is crucial for preventing various health issues such as obesity, diabetes and bone-related problems. Given the importance of nutrition in supporting children’s growth and development, particularly during the school years, understanding factors influencing mothers’ intentions to purchase healthy nutrition products for their children is essential.

The current study aims to investigate how the purchase intentions of financially independent mothers are influenced by their prior product knowledge and information search behaviour. By exploring these factors, we seek to gain insights into the decision-making process of mothers when selecting nutrition products for their children, thereby contributing to the promotion of healthier dietary choices among school-age children.

Prior product knowledge is the knowledge that mothers have about nourishment products before they start searching for information. This knowledge can come from a variety of sources, such as personal experience, word-of-mouth or advertising. The role of prior product knowledge in purchasing nourishment products for children is twofold. First, it can influence the mothers’ decision of whether or not to purchase a particular product. Mothers with positive prior knowledge about a product are more likely to purchase it, while mothers with negative prior knowledge are less likely to purchase it. Second, prior product knowledge can influence the mothers’ search for information about a product. Mothers who have little prior knowledge about a product are more likely to engage in active information searches, such as reading labels, comparing prices and reading reviews. Mothers who have more prior knowledge about a product are more likely to rely on their knowledge and experience when making a purchase decision.

Information search is the process of gathering information about a product or service before making a purchase decision. Mothers often engage in information searches when purchasing nourishment products for their children. There are many different nourishment products on the market, and it can be difficult to know which ones are the best. By engaging in information search, mothers can learn about the different options available and make an informed decision. Mothers want to make sure that the nourishment products they purchase are of high quality. By engaging in information search, mothers can learn about the quality of the products, such as the ingredients, manufacturing process and safety standards. Mothers often turn to other mothers for advice when making purchase decisions. By engaging in information searches, mothers can read reviews from other mothers and get their opinions on different nourishment products. Mothers are budget conscious and want to find the best deals on nourishment products. By engaging in information search, mothers can compare prices and find the best deals.

Researching purchase intention for nourishment products is important because it can help companies understand the factors that influence mothers’ purchase decisions. This understanding can be used to develop more effective marketing strategies, improve product development, measure the effectiveness of marketing campaigns and provide better customer service.

The buying cycle and consumer behaviour of first-time mothers are the main topics of this study, along with how they differ depending on the mother’s age, income and place of residence. They must cope with a lot of desires, objectives and anxieties when becoming a mother for the first time. These significant adjustments impact the mother’s potential self. The amount of the mother’s concern, the breadth of their information search and the evaluation stage are all examined in this study.

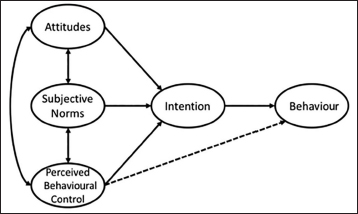

The theory of planned behaviour as shown in Figure 1, is a widely recognised framework in the field of consumer behaviour that explains the relationship between attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control and behavioural intentions (Ajzen, 1991). The theory provides a comprehensive framework for understanding how financially independent mothers’ prior product knowledge and information search can impact their purchase intention of nourishment products for their children. It emphasises the roles of attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control in shaping behavioural intentions, which, in this case, would relate to the decision to purchase specific nourishment products for their children. According to the theory, individuals’ attitudes towards a particular behaviour significantly influence their intention to engage in that behaviour. In the context of mothers purchasing nourishment products for their children, prior product knowledge plays a crucial role in shaping their attitudes. Positive prior experiences and knowledge about the benefits of certain products may lead to more favourable attitudes towards purchasing them for their children (Ajzen, 1991). The theory suggests that perceived subjective norms, or the social pressure and influence from important others, affect one’s behavioural intentions. In this research context, mothers may be influenced by the opinions and recommendations of family members, friends, healthcare professionals or other mothers in their social network regarding which nourishment products to purchase for their children. The strength of these subjective norms can be influenced by the information they have gathered through their independent information search (Ajzen, 1991). The theory posits that individuals’ perceived control over a behaviour affects their intention to engage in it. In the context of mothers purchasing nourishment products, their perceived control can be influenced by their level of product knowledge and information search. Mothers with greater product knowledge may feel more confident and capable of making informed decisions, thus impacting their perceived behavioural control over the purchase (Ajzen, 1991).

Figure 1. The Theory of Planned Behaviour.

Source: Ajzen (1991).

Review of the Literature

Prior Product Knowledge

Anderson (1979) suggests that having prior knowledge of a product can satisfy the need to understand its various features, leading to a reduced inclination to seek additional information from external sources. On the contrary, Johnson and Russo (1984) propose that prior knowledge of product attributes enables consumers to generate more questions, prompting them to seek out more information. Brucks (1985) points out that well-informed customers might seek additional information proactively, even before encountering a problem, due to their awareness of existing qualities. However, when relevant product information is lacking or ignored, highly knowledgeable customers may conclude a product’s characteristics or intended use (Alba & Hutchinson, 1987), which will be accurate only to the extent that prior knowledge is applicable.

According to Park and Lessig (1981), familiarity with a product, or prior product knowledge, significantly influences consumers’ search for, recall of and use of information when evaluating product quality and making product choices. Hayes-Roth (1977) suggest that a user’s knowledge structures or ‘schema’ become more sophisticated as their familiarity with a product increases. Both traditional (Howard & Sheth, 1969) and contemporary (Bettman, 1987) consumer choice models include the impact of previous knowledge of or familiarity with consumers’ information processing. This notion is supported by the influence of past purchase or usage experience with the relationship between price and perceived quality (Valenzi & Eldridge, 1972).

Katila and Ahuja (2022) provide further examples of the significance of organisational knowledge in the creative process of developing new products and services. They defined ‘prior knowledge’ as specialised knowledge acquired through work experience.

According to Dahl et al. (1999), the perceived novelty of a product or service relates to its originality, freshness and distinctiveness as experienced by individuals.

In a study by Johnson and Russo (1984), it was found that individuals with prior product knowledge or information stored in their memory tend to have an easier time processing information, allowing them to focus on relevant task-related information. Alba (1987) often operationalises consumers’ objective or self-reported knowledge levels through prior knowledge.

Lewandowsky and Kirsner (2000) suggest that the effects of prior knowledge indicate that consumers with extensive knowledge in a specific domain tend to approach their goals with a greater sense of urgency.

Information Search

Dahl et al. (1999) noted that consumers engage in information search, a process through which they collect diverse information from various channels. This reliance on word of mouth (abbreviated as w-o-m) for recommendations when considering new product purchases is also evident in the work of Anderson in (1979). In contrast to impersonal information sources, w-o-m communications are described as immediate, participatory and a source of credible and sought-after information, as suggested by McEachern and Warnaby (2008).

Brucks (1985) highlighted that clients take their time to search for product information before making purchase decisions. In the field of library and information science, the Information Search Process (ISP) is a six-stage model of information-seeking behaviour, initially proposed by Zhang et al. (2010). Despite the apparent ease of information gathering on the Internet, Dickinger (2011) noted that customers still make purchases without having all the necessary facts due to existing search and processing costs.

According to Duncan and Olshavsky (1982), the Internet serves as a marketing medium with both unique and shared characteristics compared to other marketing channels. For instance, the Internet can efficiently store vast amounts of data in various virtual locations, making it accessible to users as needed. Contrasts between conventional and virtual (Internet-based) marketplaces are outlined by Zeithaml (1998). In the virtual marketplace, transactions are primarily centred around information about goods and services, unlike traditional marketplaces, where tangible products and services play a more central role. Electronic interactions on a screen replace face-to-face interactions in the virtual marketplace.

Johnson and Russo (1984) emphasises the significance of Internet interactions as they contribute to customer value and foster relationship development. Customers often view the Internet as an additional sales channel, information search tool and a source when making purchases of goods and services. They further posit that individuals categorise things and events based on perceived similarities and resemblances in response to the overwhelming volume and diversity of information in their surroundings.

Purchase Intention

Carlson et al. (2005)discuss the idea that initially springs to mind for an individual when contemplating anything is their intention to make a purchase. This includes considerations about their feelings towards a specific product and the emotions or actions they might undertake if they were to acquire the same item from the same brand. Such justifications consistently amplify a brand’s purpose and its encouragement for purchase. It is worth noting that both positive and negative effects can arise from this specific product. Arnould and Thompson (2024) highlight that a consumer’s decision to purchase a brand or product is influenced not only by their attitude towards that brand but also by their exposure to other competing brands. The consumer culture theory has been developed with the help of brand purchase intentions in the context of human nature and environmental impacts.

Ajzen (1991) emphasises that a consumer’s behaviour is positively influenced by their purchase intention. Furthermore, there are precursors to the intention to purchase luxury brands, as explored by Mitchell (1996). Moe (2004) defines purchase intentions as pre-formed plans to acquire specific goods or services in the future, though their execution depends on an individual’s capacity to do so.

McEachern and Warnaby (2008) suggest that a customer’s purchase intention is reflected in their thoughts. Similarly, research has found that customers typically identify the item they wish to buy, seek information about it, evaluate it, make the purchase and provide feedback. They further emphasise that customer behaviour during purchases is influenced by factors such as brand reputation, price, quality, awareness of leisure and innovation and other alternatives as well as impulsive tendencies.

Zhang et al. (2010) note that, traditionally, the term ‘intention’ has been used to describe the factors that influence and motivate customers to buy products and services. They also highlight that purchase intention represents an implicit commitment to repurchase an item on future shopping trips. Brands significantly affect consumers’ purchase intentions, making it a fundamental concept in marketing literature. The relationship between purchase intentions and actual purchasing behaviour is a focal point for marketing researchers, and multiple studies have established a positive link between them (Morwitz & Schmittlein, 1992).

According to the theory of reasoned action (TRA), intention is the key determinant of behaviour, signifying an individual’s likelihood to engage in a specific action (Zhang et al., 2010). In the context of consumer purchasing behaviour, purchase intention is defined as a consumer’s intention to buy a product in the future (Hsu & Tsou, 2011).

Kolyesnikova et al. (2010) suggest that price, perceived quality and perceived value can all influence the intention to make a purchase, with internal and external factors playing a role in a buyer’s decision-making process. Hsu and Tsou (2011) argue that purchase intention is a valuable predictor of actual purchasing behaviour and has garnered significant attention in scholarly research. They describe purchase intention as an individual's perceived likelihood of engaging in specific activities, while Dickinger (2011) recognises the significance of the desire to purchase one of the consumer's intentions regarding products. Pennington-Gray and Schroeder (2013) define purchase intention as the likelihood that a customer will consider buying a specific brand; those who feel a stronger connection and sensory value with the brand tend to elevate their intention to purchase its products. Shafizadeh (2007) suggest that a higher purchase intention increases the likelihood of a buyer making a specific purchase. Additionally, they contend that purchase intention is the most accurate predictor of how buyers will behave during the purchasing process.

Prior Product Knowledge and Information Search

Bettman and Park (2012) conducted research indicating that the link between one’s knowledge of a product and their act of seeking information about it is contingent upon the individual’s motivation to seek such information. Prior knowledge pertains to what consumers already know about a product, shaping their level of expertise, defined as their ability to effectively handle tasks related to that product. Kolyesnikova et al. (2010) proposed that when consumers seek information before making a decision, they primarily rely on their existing knowledge of the product. This consumer knowledge encompasses their experiences with the product, their understanding of it and their overall comfort level. It refers to the internalised information guiding consumers in their decision-making process. Various researchers, such as Chao and Gupta (1995), Duncan and Olshavsky (1982) and Ratchford (2017), have studied the relationship between product knowledge and a consumer’s pre-purchase search behaviour.

Additionally, Anderson et al. (1979) and Murray et al. (1991) have found a negative correlation between prior product knowledge and the depth of information search. According to Johnson and Russo (1984) and Ozanne and Brucks (1985), customers are more inclined to seek additional information when they are aware of the characteristics of a product. Ratchford et al. (2017) argue that knowledge initially exerts a greater influence than competence later in the search process, resulting in an inverted-U-shaped relationship between past knowledge and information search.

Every time a customer decides to purchase a product, they face numerous options, each claiming to meet their needs. Their criteria, existing product knowledge and the information they gather during the search process all impact their final product choice, as noted by Punj and Brookes (2021). According to Brucks (1985) and Ratchford et al. (2017), prior product knowledge reflects the consumer’s perception of their familiarity with a specific product category. According to Biswas (2004), customers with limited product knowledge derive more value from information, while those with extensive product knowledge also perceive their abilities as higher, as Vroom (1964) suggests. The relationship between prior product knowledge and the motivation to search is influenced by the perceived value of additional information, as indicated by Shafizadeh’s research in 2017. Furthermore, product participation and knowledge frequently influence information search and purchase intention, as observed by Lin and Chen (2016).

H1: There is a positive relationship between prior product knowledge and information search.

Information Search and Purchase Intention

Purchase decisions are frequently characterised by careful consideration and thorough information gathering, which serve to familiarise customers with the product category. This viewpoint is supported by McEachern and Warnaby (2008). In line with the information-processing perspective, consumers utilise various cues to navigate their decision-making process. These cues are triggered from memory when a buying decision is required, forming a network through which diverse stimuli can influence choices (Sternthal & Craig, 1984). The involvement and knowledge of a product often play a notable role in shaping information search and purchase intentions (Johnson and Russo, 1984). According to research by the Boston Consulting Group (2000), 28% of consumers’ purchase attempts were deemed unsuccessful due to issues like locating desired goods, transaction completion or overall satisfaction during the purchase.

Ariely (2000) suggests that consumers’ search activity can enhance customer satisfaction and increase the inclination to make purchases among visitors. Moe (2004) has presented compelling findings that establish a strong connection between online search behaviour, purchasing intentions and online search habits. Information overload can be a challenge for customers, as an excessive amount of information can complicate decision-making (Grether & Wilde, 2013). Excessive packaging information can also lead to suboptimal purchase choices (Speller et al., 2014). Consumer product knowledge has been extensively studied across various product categories, underscoring its significant influence on information processing and decision-making (Bettman & Park, 1980; Brucks, 1985; Carlson et al., 2005; Mitchell 1996).

Grewal et al. (1998) discovered that the volume of information did not consistently impact customer purchasing behaviour. Paradoxically, an excess of information, as highlighted by Johnson and Russo (1984), can lead to information overload, which is responsible for diminishing the quality of purchasing decisions.

H2: There is a positive relationship between information search and purchase intention.

Prior Product Knowledge and Purchase Intention

In the research conducted by Alba and Hutchinson (1987), consumer knowledge is defined as the information consumers gather about products over time, acquired through exposure to various sources like advertising, salespeople or actual product usage. This knowledge forms the basis on which consumers rely to guide their buying choices. Scholars such as Kolyesnikova et al. (2010), Kerstetter and Cho (2014) and Alba and Hutchinson (1987) emphasise the crucial role of consumer knowledge in influencing purchase intentions and call for more scholarly attention to this area. Consumer knowledge encompasses aspects such as familiarity, skill and experience, and it exhibits multiple dimensions. Numerous studies have consistently demonstrated that the extent of consumer engagement and product knowledge directly impacts their information search and purchase intentions.

Numerous research efforts have been dedicated to examining consumer product knowledge across a wide range of product categories, highlighting its significant influence on information processing and decision-making (Bettman & Park, 1980; Brucks, 1985; Carlson et al., 2005; Mitchell, 1996). Beatty and Smith (1987) define product knowledge as a consumer’s evaluation of a product’s suitability for purchase, taking into account their past experiences with it. Depending on their familiarity with a product, consumers develop different structures of product knowledge (Park & Lessig, 1981). Purchase intentions are also notably affected by the level of consumer product knowledge.

Ozanne and Brucks (1985) conclude that consumers with a strong grasp of product knowledge tend to assess a product primarily based on its quality because of their confidence in their knowledge, which leads to a greater inclination to form purchase intentions as they recognise the product’s value. Duncan and Olshavsky (1982) add that consumers who possess extensive product knowledge are more likely to prioritise a product’s quality over its price or any price reductions when making purchasing decisions. According to Zeithaml (1998), customers primarily consider a product’s intrinsic value, informed by their product knowledge when deciding whether or not to make a purchase. Furthermore, Grewal et al. (1998) argue that consumers are more sensitive to a company’s product quality when they perceive a positive brand image. However, it is essential to acknowledge that customers often face time constraints when making their decisions.

H3: There is a positive relationship between prior product knowledge and purchase intention

Research Gaps and Motivation

The study aims to address several significant research gaps in the field of consumer behaviour and nutrition.

The motivation behind this study stems from the recognition of the importance of promoting healthy dietary habits among children, particularly in the context of increasing concerns about childhood obesity and related health issues. Financially independent mothers play a significant role in shaping their children’s dietary habits through their purchasing decisions. Therefore, understanding the factors influencing their purchase intention regarding nourishment products for their children is crucial for developing effective interventions and marketing strategies aimed at promoting healthier dietary choices. By addressing the identified research gaps, this study seeks to contribute to the body of knowledge on consumer behaviour and nutrition, ultimately aiming to support efforts to improve children’s health and well-being.

Objectives

The study aims to investigate several key objectives concerning the behaviours of financially independent mothers in relation to nourishment products for their children. First, it seeks to examine the extent to which prior product knowledge influences the information search habits of these mothers when considering nourishment products for their children. Second, it aims to explore the relationship between information search behaviour and purchase intention among financially independent mothers in this context. Lastly, the study aims to analyse the impact of prior product knowledge on the purchase intention of nourishment products for their children by financially independent mothers. By addressing these objectives, the research aims to provide insights into the decision-making process of financially independent mothers when selecting nourishment products for their children and to identify potential areas for intervention or improvement in marketing strategies aimed at this demographic.

Rationale of the Study

The rationale behind conducting the study stems from the critical need to understand the decision-making process of financially independent mothers regarding the selection of nourishment products for their children. With the increasing prevalence of financially independent mothers who are actively involved in household purchasing decisions, particularly concerning products related to the health and well-being of their children, it becomes imperative to explore the factors that influence their purchase intentions in this specific domain.

First, prior product knowledge is recognised as a significant determinant of consumer behaviour. Understanding how the level of prior product knowledge influences the decision-making process of financially independent mothers when choosing nourishment products for their children is crucial for marketers and policymakers. By elucidating the relationship between prior product knowledge and purchase intention, the study aims to provide insights into the extent to which mothers rely on their existing knowledge and experience when making purchasing decisions in this domain.

Second, the role of information search behaviour cannot be understated in today’s information-rich environment. Financially independent mothers have access to a plethora of information sources, ranging from traditional media to online platforms, which can significantly influence their perceptions and attitudes towards nourishment products for their children. Investigating the impact of information search behaviour on purchase intention allows for a deeper understanding of how mothers gather, process and utilise information in their decision-making process. Moreover, identifying the sources and types of information that are most influential in shaping purchase intentions can inform marketing strategies aimed at targeting this demographic more effectively.

Furthermore, by focusing specifically on nourishment products for children, the study addresses a particularly important aspect of consumer behaviour with significant implications for public health. Ensuring that financially independent mothers make informed and health-conscious decisions regarding the nourishment of their children is essential for promoting child well-being and preventing health-related issues in the long term.

By addressing this research gap, the study aims to contribute valuable insights into both academia and industry, ultimately informing marketing strategies, public health initiatives and consumer education efforts targeted at this demographic.

Methodology

Data Source

The data for this study was collected through surveys administered to financially independent mothers who are responsible for purchasing nourishment products for their children. Surveys were distributed either electronically or in-person, depending on the preferences and accessibility of the participants.

Sample Frame

The population targeted for the study consisted of financially independent mothers of children aged between 5 and 12 years. The sample size was determined to be 181. A financially independent rational mother was considered as a sampling element in the study. Non-probability purposive sampling techniques were employed to identify the respondents.

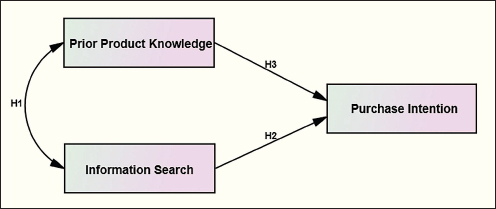

Empirical Model

The link between prior product knowledge, information search and purchase intention as shown in Figure 2, was measured using a standardised questionnaire. The questionnaire utilised was based on the work of Phan and Mai (2016). The scale used was of the Likert type, with a sensitivity of 5, where extreme values of 1 and 5 denoted strongly disagreeing and strongly agreeing, respectively. Reliability of the questionnaire was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. Exploratory factor analysis was conducted to identify underlying components in the study variables of prior product knowledge, information search and purchase intention. To determine the causal association between prior product knowledge, information search and purchase intention, multiple regression analysis was employed. The data analysis was conducted using SPSS AMOS.

Figure 2. Research framework showing the interactions between prior product knowledge, information search and purchase intention.

Data Analysis

Descriptive Analysis

In this study, the distribution of ages within four distinct age groups (18–25, 26–33, 34–41 and 41 and above) was analysed, providing valuable insights into the demographic composition of the sample. The 26–33 age group exhibited the highest mean age (14.5333) and median age (17), suggesting a relatively older distribution compared to other groups. Conversely, the 41 and above age group had the lowest mean age (10.1667) and median age (8.5000), indicating a younger distribution within this category. Variance and standard deviation values revealed varying degrees of age diversity within each group, with the 34–41 age group showing the highest variance (25.363) and standard deviation (5.03613), indicating greater age diversity. The consistent range of 16 across all age groups signifies a similar spread of ages within each category.

Furthermore, three different brands—PediaSure, Protein X and Complan—were analysed in terms of their nutritional content. Statistical measures provided insights into the central tendency and variability of these brands’ nutritional profiles. Interestingly, all three brands exhibited similar mean nutritional content, with PediaSure at 13.6222, Complan at 13.7647 and Protein X at 13.5686, suggesting comparable nutritional value on average. Median values closely aligned with the mean, indicating relatively symmetric data distributions. However, Complan demonstrated the highest variance (22.301) and standard deviation (4.72241) among the brands, implying greater variability in its nutritional content compared to the others. Conversely, Protein X exhibited the lowest variance (19.170) and standard deviation (4.37838), indicating more consistent nutritional content. Additionally, all three brands showed a consistent range of 14, suggesting a similar spread in their nutritional values.

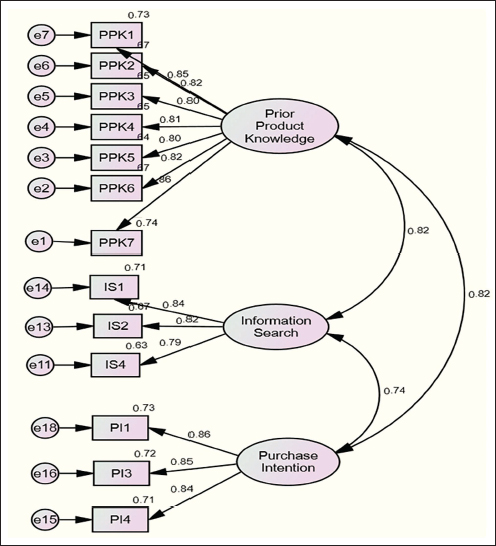

Figure 3. Measurement Model.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Measurement Model

The study assessed the convergent validity, average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR) of the constructs—prior product knowledge, information search and purchase intention. Following the guidelines of Hair et al. (2013), with a cut-off value of 0.5, the AVE and CR were initially estimated. Similarly, for loading values, a threshold of 0.7 was considered acceptable. Although loadings exceeding 0.7 are preferred, loadings between 0.5 and 0.7 are deemed appropriate if the AVEs surpass 0.5 (Ramayah et al., 2018). In this study, all loading values exceeded 0.7, with AVEs greater than 0.5, indicating acceptable convergent validity (Table 1). Notably, AVE values close to or exceeding 0.7 are widely recognised in current research practices. AVE values below 0.5 imply that items explain more errors than the variation in the constructs, hence failing to meet the measurement model’s criteria. Furthermore, composite reliability, akin to Cronbach’s alpha, signifies the internal consistency of scale items (Netemeyer, 2003). According to Morgan (2005), it represents the extent of score variance captured by the overall scale score variance. In this study, the internal consistency of each item within the scales was found to be satisfactory, surpassing the threshold of 0.7 for composite reliability across all constructs, affirming the validity and reliability of the measurement model.

The reliability analysis of the constructs—prior product knowledge, information search and purchase intention—yielded Cronbach’s alpha values exceeding the threshold at 0.936, 0.929 and 0.907, respectively, indicating high internal consistency. Additionally, Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) values for each construct were found to be satisfactory, with values of 0.922, 0.913 and 0.836, respectively, suggesting that the sample size for the investigation was adequate. Chi-square analysis revealed significant findings at the 0% level of significance, with values of 955.133, 898.177 and 467.172, respectively, rejecting the null hypothesis and indicating that the data are suitable for further statistical analysis. Figure 3 shows the coefficients of determination (R2) between prior product knowledge and purchase intention, prior product knowledge and information search and information search and purchase intention were 0.82, 0.82 and 0.74, respectively, indicating a strong association between the postulated relationships. Moreover, discriminant validity analysis showed that each scale was unrelated to the other scales being utilised, as listed in Table 2.

After refining the measurement model by removing certain items from the scales of information search and purchase intention, a well-fitting model was achieved. The Chi-square value, indicating 79.238 at a significance level of 6.9%, served as a measure to evaluate the goodness of fit of the model. All acceptable index values were found to meet the established thresholds, confirming the adequacy of the model in representing the relationships between the constructs.

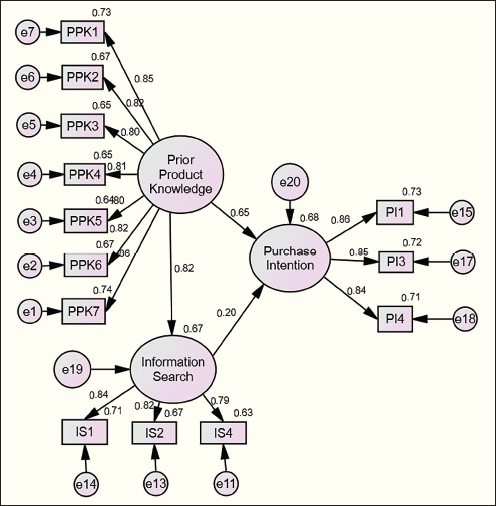

Structural Equation Modelling

The study employed structural equation modelling (SEM) as shown in Figure 4, to investigate the impact of prior product knowledge and information search on the purchase intention of nourishment products for children by financially independent mothers. The analysis was conducted on a sample of 181 participants. The SEM model was determined to be recursive, and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using AMOS software. Thirteen endogenous variables, representing observed variables, were included in the analysis to examine the relationships among prior product knowledge, information search behaviour and purchase intention.

The statistical analysis as shown in Table 3, revealed that the data ranged from 1 to 5, with a sample skewness of 0.542 and kurtosis of −0.764, indicating a slightly positively skewed distribution. However, these values fall within an acceptable range, suggesting a relatively normal distribution. Specifically, a skewness value close to 0 (0.03) and a kurtosis value close to 3 (2.96) indicate a symmetric distribution, further supporting the assumption of normality. The use of maximum likelihood estimation was prevalent, emphasising estimations to maximise probability. These findings indicate that the data met the assumptions necessary for further analysis, ensuring the robustness of the subsequent statistical modelling.

One of the key measures of fit quality in SEM is the chi-square test. In this study, the chi-square value was found to be 79.238 with 62 degrees of freedom, resulting in a significance value of 0.069, which is greater than the conventional significance threshold of 0.05. Despite the chi-square test indicating a lack of perfect fit, the CMIN/DF ratio, which assesses model fit relative to degrees of freedom, was calculated to be 1.278, well below the threshold of 2. This suggests that the model adequately fits the data. The results of the SEM are presented in Table 4, providing further insights into the relationships between prior product knowledge, information search behaviour and purchase intention of nourishment products for children among financially independent mothers.

In the present study, the fit indices for the measurement model were evaluated and found to be satisfactory. These indices, along with their universally acknowledged cutoff values, are presented in Table 5 and Table 6, indicating the adequacy of the model in capturing the underlying data structure. Following the assessment of the model’s fitness, an alternative hypothesis was formulated based on the regression output table, which provided insights into the relationships between prior product knowledge, information search behaviour and purchase intention of nourishment products for children among financially independent mothers.

Figure 4. Structural Equation Modelling.

H1: There is a positive relationship between prior product knowledge and information search.

The regression analysis revealed a significant association between prior product knowledge and information search with purchase intention among financially independent mothers. By dividing the regression weight estimate by its standard error, a z-value of 10.305 was obtained (z = 0.798/0.073), indicating a strong correlation. The calculated R² value of 0.754 further supports this association, with a standard error of 0.073. With the alternative hypothesis not being ruled out at the 0% level of significance, it can be concluded that both prior product knowledge and information search are significantly correlated with purchase intention. This finding underscores the importance of understanding how mothers’ knowledge and information-seeking behaviours influence their purchasing decisions regarding nourishment products for their children, providing valuable insights for marketers and policymakers aiming to promote healthier choices in this demographic.

H2: There is a positive relationship between prior product knowledge and purchase intention.

In analysing the impact of prior product knowledge and information search on the purchase intention of nourishment products for children by financially independent mothers, regression analysis was conducted. Dividing the regression weight estimate by its standard error yielded a z-score of 5.525 (0.723/0.131), indicating a strong and significant association. The reestablished association, as indicated by the R2 value of 0.244, also had a standard error of 0.131. This substantial and significant association between prior product knowledge and purchase intention is evident, with the alternative hypothesis being upheld at a 0% level of significance, affirming the importance of prior product knowledge in influencing mothers’ purchase intentions regarding nourishment products for their children.

H3: There is a positive relationship between information search and purchase intention.

The association between information search and purchase intention was examined using regression analysis. The regression weight estimate was calculated as 0.723, with a standard error of 0.140. Dividing the regression weight estimate by its standard error yielded a z-value of 1.742. Additionally, the coefficient of determination (R2) was determined to be 0.244. Based on these findings, the hypothesis that there is a significant relationship between information search and purchase intention was disproved at the 0% level of significance. This suggests that the connection between information search and purchase intention is weak, indicating that other factors may play a more significant role in influencing purchase intention among financially independent mothers when it comes to nourishment products for their children.

Discussion

The findings of this empirical study show that prior product knowledge and information search affect the purchase intention for items of children’s health and nutrition. This finding expands and is consistent with that of a recent study that looked at Indian rational mothers’ intentions to buy children’s health and nutrition items. According to the current study, consumers’ prior product awareness and information seeking increase their propensity to buy children’s health and nutrition items. Prior product knowledge and the depth of information search are negatively correlated by Anderson et al. (1979), Murray (1991) and others. According to Coupey et al. (1998), Johnson and Russo (1984) and Ozanne and Brucks (1985), customers are more likely to seek out further information when they are aware of the characteristics of a product. They contend that knowledge initially has a greater influence than competence later in the search process, resulting in an inverted-U-shaped link between past knowledge and information search. According to Ariely (2000), consumers’ search activity may boost customer satisfaction and increase visitors’ desire to make purchases. More (2013) provided intriguing findings demonstrating that online search mode is strongly related to purchasing intention and also linked the two to online search habits and purchase intentions. Customers may experience information overload; therefore, having more information may make it more difficult to make decisions (Grether & Wilde, 2013). An excessive quantity of packaging information may result in worse purchasing choices (Speller et al., 1974). Consumer product knowledge has been the subject of numerous studies that have looked at a wide range of product categories; this shows the significant influence that knowledge has on how information is processed and how decisions are made (Bettman & Park, 1980; Brucks, 1985; Carlson et al., 2005; Mitchell, 1996).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the findings of this study reveal a nuanced relationship between prior product knowledge, information search and purchase intention among financially independent mothers regarding nourishment products for their children. The results suggest a strong association between prior product knowledge and information search, indicating that mothers who possess greater knowledge about nourishment products are more likely to engage in information search behaviours. Furthermore, the study highlights a significant relationship between prior product knowledge and purchase intention, underscoring the importance of mothers’ existing knowledge in influencing their intentions to purchase nourishment products for their children. However, the relationship between information search and purchase intention appears to be less substantial, as evidenced by the refutation of the alternative hypothesis at the 0% level of significance. These findings emphasise the complexity of factors influencing mothers’ purchasing decisions in this context and underscore the need for further research to explore the underlying mechanisms driving these relationships. Ultimately, understanding the interplay between prior product knowledge, information search and purchase intention can inform targeted interventions and marketing strategies aimed at promoting healthier dietary choices for children among financially independent mothers.

Managerial Implications

The managerial implications derived from the findings of this study offer actionable insights for marketers, policymakers, healthcare professionals and brands aiming to promote healthier choices among financially independent mothers when purchasing nourishment products for their children. Marketers can effectively utilise mothers’ prior product knowledge as a means of segmentation, recognising that informed mothers may require different marketing approaches compared to those with less knowledge. Tailored marketing strategies can be developed to address the distinct needs and preferences of these segments. Providing easily accessible and reliable product information is crucial, as mothers often conduct information searches before making purchase decisions. Brands can positively influence mothers’ purchase intentions by ensuring that accurate and comprehensible product information is readily available. Additionally, insights gleaned from mothers’ prior knowledge can inform product development, enabling companies to design products that align with mothers’ specific needs and expectations. Policymakers can leverage data on mothers’ prior product knowledge to implement targeted educational programmes or regulations that promote healthier choices. Encouraging mothers to actively seek information about nourishment products empowers them to make better decisions, and brands can support this by providing resources and establishing trust through transparent and honest marketing practices. Collaboration with healthcare professionals can further strengthen mothers’ confidence in their product choices. Moreover, continuous feedback from mothers can aid in product improvement, and engagement with online communities and social media platforms allows brands to share educational content and build relationships with their target audience responsibly. Finally, brands must remain mindful of the ethical implications of marketing to mothers and children, prioritising transparency, responsible advertising practices and a commitment to children’s well-being in all marketing efforts.

Limitations

This study has some limitations; to guarantee result generality, more research could be done utilising a bigger sample size. It is advised to the researchers that since the study utilised a non-probability sampling approach, future research might be conducted utilising a probability sample technique. Indian respondents made up the study’s sample. It is possible that the outcome cannot be applied globally. In further research, it may be beneficial to utilise a meticulously crafted survey instrument and explore alternative data collection methods to mitigate respondents’ undue defensiveness, thus diminishing the inclination towards individual bias.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all those who contributed to the completion of this research project. First, we extend our appreciation to our colleagues and peers for their valuable insights and discussions throughout this study. We also want to acknowledge the support and encouragement provided by our families and friends, whose unwavering belief in our work has been a constant source of motivation. Furthermore, we would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback and suggestions, which have significantly enhanced the quality of this article. The authors are grateful to the anonymous referees of the journal for their extremely useful suggestions to improve the quality of the article. Usual disclaimers apply. Finally, we express our heartfelt gratitude to all the participants who generously shared their time and insights, without whom this research would not have been possible.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

Gaurav Soin  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9069-168X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9069-168X

Nischay K. Upamannyu  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9691-3642

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9691-3642

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice-Hall.

Alba, J. W., & Hutchinson, J. W. (1987). Dimensions of consumer expertise. Journal of Consumer Research, 13(4), 411.

Anderson, R. D., Engledow, J. L., & Becker, H. (1979). Evaluating the relationships among attitude toward business, product satisfaction, experience, and search effort. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(3), 394.

Ariely, D. (2000). Controlling the information flow: Effects on consumers’ decision making and preferences. Journal of Consumer Research, 27(2), 233–248.

Arnould, E., & Thompson, C. J. (2024). Consumer culture. Elgar Encyclopedia of Consumer Behavior, 31(4), 81–84.

Atuahene-Gima, K. (2003). The effects of centrifugal and centripetal forces on product development speed and quality: How does problem-solving matter? Academy of Management Journal, 46(3), 359–373.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

Beatty, S. E., & Smith, S. M. (1987). External search effort: An investigation across several product categories. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(1), 83.

Bettman, J. R., & Park, C. W. (1980). Effects of prior knowledge and experience and phase of the choice process on consumer decision processes: A protocol analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 7(3), 234.

Bettman, J. R., & Sujan, M. (1987). Effects of framing on evaluation of comparable and Noncomparable alternatives by expert and novice consumers. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(2), 141.

Biswas, D. (2004). Economics of information in the web economy. Journal of Business Research, 57(7), 724–733.

Brucks, M. (1985). The effects of product class knowledge on information search behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 12(1), 1.

Carlson, C., Carlson, C., Carlson, C., Carlson, C., Carlson, C., Carlson, C., & Carlson, C. (2005). Youth with influence: The youth planner initiative in Hampton, Virginia. Children, Youth and Environments, 15(2), 211–226.

Chao, P., & Gupta, P. B. (1995). Information search and efficiency of consumer choices of new cars country-of-origin effects. International Marketing Review, 12(6), 47–59.

Coupey, E., Irwin, J., & Payne, J. (1998). Product category familiarity and preference construction. Journal of Consumer Research, 24(4), 459–468.

Dahl, D. W., Chattopadhyay, A., & Gorn, G. J. (1999). The use of visual mental imagery in new product design. Journal of Marketing Research, 36(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151912

Dickinger, A., & Stangl, B. (2011). Online information search: Differences between goal-directed and experiential search. Information Technology & Tourism, 13(3), 239–257.

Duncan, C. P., & Olshavsky, R. W. (1982). External search: The role of consumer beliefs. Journal of Marketing Research, 19(1), 32.

Grether, D. M., & Wilde, L. L. (1983). Consumer choice and information. Information Economics and Policy, 1(2), 115–144.

Grewal, D., Krishnan, R., Baker, J., & Borin, N. (1998). The effect of store name, brand name and price discounts on consumers' evaluations and purchase intentions. Journal of Retailing, 74(3), 331–352.

Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T., Ringle, C., & Sartedt, M. (2013). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS). Sage Publications.

Hayes-Roth, B., & Hayes-Roth, F. (1977). Concept learning and the recognition and classification of exemplars. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 16(3), 321–338.

Hsu, H. Y., & Tsou, H. (2011). Consumer experiences in online blog environments questionnaire. PsycTESTS Dataset.

Jacoby, J., Speller, D. E., & Kohn, C. A. (1974). Brand choice behavior as a function of information load. Journal of Marketing Research, 11(1), 63.

Johnson, E. J., & Russo, J. E. (1984). Product familiarity and learning new information. Journal of Consumer Research, 11(1), 542.

Katila, R., & Ahuja, G. (2002). Something old, something new: A longitudinal study of search behavior and new product introduction. Academy of Management Journal, 45(6), 1183–1194.

Kerstetter, D., & Cho, M. (2004). Prior knowledge, credibility and information search. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(4), 961–985.

Kolyesnikova, N., Laverie, D. A., Duhan, D. F., Wilcox, J. B., & Dodd, T. H. (2010). The influence of product knowledge on purchase venue choice: Does knowing more lead from bricks to clicks? Supply Chain Forum: An International Journal, 11(1), 28–40.

Lewandowsky, S., & Kirsner, K. (2000). Knowledge partitioning: Context-dependent use of expertise. Memory & Cognition, 28(2), 295–305.

McEachern, M. G., & Warnaby, G. (2008). Undefined. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 32(5), 414–426.

Mitchell, A. A., & Dacin, P. A. 1996. The assessment of alternative measures of consumer expertise. Journal of Consumer Research, 23(3), 219.

Moe, W. W., & Peter S., F. (2004). Dynamic conversion behavior at e-commerce sites. ScholarlyCommons, 50, 326–335.

Morwitz, V. G., & Schmittlein, D. (1992). Using segmentation to improve sales forecasts based on purchase intent: Which “Intenders” actually buy? Journal of Marketing Research, 29(4), 391.

Murray, K. B. (1991). A test of services marketing theory: Consumer information acquisition activities. Journal of Marketing, 55(1), 10.

Netemeyer, R. G., Bearden, W. O., & Sharma, S. (2003). Scaling procedures: Issues and applications. Thousand Oaks, 11(8), 206.

Ozanne, J. L., Brucks, M., & Grewal, D. (1992). A study of information search behavior during the categorization of new products. Journal of Consumer Research, 18(4), 452.

Pennington-Gray, L., Kaplanidou, K., & Schroeder, A. 2012. Drivers of social media use among African Americans in the event of a crisis. Natural Hazards, 66(1), 77–95.

Ratchford, B. T., Lee, M., & Talukdar, D. (2017). Consumer use of the internet in search for automobiles. Review of Marketing Research, 40(2), 81–107.

Sternthal, B., & Craig, C. S. (1973). Humor in advertising. Journal of Marketing, 37(4), 12.

Morgan, T., & Brunner, H. (2005). Hypertension: Etiology. Encyclopedia of Human Nutrition, 26(1), 499–505.

Park, C. W., & Lessig, P. V. (1981). Familiarity and its impact on consumer decision biases and heuristics. Journal of Consumer Research, 8(2), 223.

Phan, T. A., & Mai, P. H. (2016). Determinants impacting consumers’ purchase intention: The case of fast food in Vietnam. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 8(5), 56.

Shafizadeh, M. (2007). Relationships between goal orientation, motivational climate and perceived ability with intrinsic motivation and performance in physical education University students. Journal of Applied Sciences, 7(19), 2866–2870.

Valenzi, E. R., Miller, J. A., Eldridge, L. D., Irons, P. W., & Solomon, R. J. (1972). Individual differences, structure, task, and external environment and leader behavior: A summary. Management Research Center: The University of Rochester, 49, 75–125.

Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52(3), 2–22.

Zhang, J., Beatty, S. E., & Mothersbaugh, D. (2010). A CIT investigation of other customers’ influence in services. Journal of Services Marketing, 24(5), 389–399.