1 XLRI Xavier School of Management, C. H. Area (East), Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

In this article we explore middle-level managers’ stories of their experiences in which they were either empowered or disempowered by organisational leadership. An exploration of the stories reveals how leaders can, inadvertently, erode the power and the authority of middle-level managers. An unintended consequence of leadership’s involvement in decisions that are middle mangers’ domain, disempowerment at the middle management level in an organisation arising out of leadership decisions offers an alternate way to explore and understand leadership and middle-management disempowerment in organisations.

Disempowerment, middle management, dysfunctional leadership, cynicism, engagement, decision-making, qualitative research

Introduction

Middle-level managers often have a difficult existence in organisations. Often caught between frontline problems, which often require immediate intervention, and the top management, which seldom delegates sufficient authority down the hierarchy, their dilemmas are commonly misinterpreted as middle-management incompetence or resistance (Fenton-O’Creevy, 1998, 2001). Negative perceptions towards middle management have led to widespread predictions of a utopian future down the corner when organisations would rely on self-managed employees and do away with middle managers (e.g., see Batt, 2004). This discourse exists despite significant literature highlighting the role of managers both in normal times and in times of organisational renewal (e.g., Battilana et al., 2022; Foss & Klein, 2022), including situations where the middle managers represent the public face of the organisation (Cioffi et al., 2024). While that future has yet to materialise, middle management continues to remain the common target in cost cutting and downsizing during troubled times (Balogun & Johnson, 2004). While there has been no complete replacement of the role of middle managers in a significant manner since the role is crucial in the implementation of an organisation’s strategic and operational goals, the middle managers remain, in most cases, underappreciated and unacknowledged in both academic and mainstream publications with few notable exceptions (e.g., Prado, 2022). In this article, we present our research findings on disempowerment amongst middle managers due to leadership styles/interventions using managers’ stories. The ensuing segments of this scholarly work will undertake an exhaustive examination of the subject matter, encapsulating a multitude of facets to furnish a comprehensive understanding. The ‘Review of Literature’ section will probe into extant research pertinent to dysfunctional leadership, disengagement and disempowerment. After this, the ‘Objectives’ section will delineate the explicit goals and objectives of the study, elucidating the anticipated outcomes.

The ‘Theoretical Framework’ will lay down the conceptual foundations steering the research, while the section on ‘Methodology’ will expound on the research design, data-gathering methods and analytical strategies employed in the study. Following this, the ‘Analysis’ section will exhibit the findings and interpretations derived from the data, transitioning into the ‘Discussion’ section, where these results will be critically scrutinised and contextualised.

Subsequently, the ‘Conclusion’ section will give a recapitulation of the principal findings. In addition, the article will delve into the ‘Managerial Implications’ of the research findings, including practical applications for organisational leadership. Finally, the ‘Limitations’ section will address the constraints or challenges encountered during the research process, offering transparency to the study’s scope and potential limitations.

Review of Literature

Officers in the middle of the pyramids are a vital link between organisational apex and the frontline employees, crucial towards implementation of strategies (Tarakci et al., 2023) and drivers of leadership’s ambidexterity (Fernández-Mesa et al., 2023). Driven towards organisational goals and yet dependent on top management leadership for direction and support, middle managers often face a tough situation. They are people with limited sanctioned authority, yet they are the frontline defence for the top management against the daily hassles of managing customers, workers, powerful stakeholders like worker unions as well as other external stakeholders, creating vital communication bridges for vertical and horizontal interactions across organisational structures (Tarakci et al., 2023). Middle managers also create the current narrative for the frontline employees (Sasaki et al., 2024), influencing the frontline employees. Despite their demanding roles and the stressful nature of their work, there is not much love for the middle-level managers and they are often labelled as obstructions to successful organisational effectiveness and efficiency via high-level employee involvement practices (e.g., Fenton-O’Creevy, 2001; Martela, 2023).

Despite the negative perspective, there have been studies indicating positive impact as well. Yang et al. (2010) in their study on Chinese organisations obtained support for middle-level transformational leadership styles impacting frontline employees’ job performance, including value creation via creativity (Faix, 2023), which is dependent on creating a supporting ecosystem for employees located down the organisational pyramid. Similar appeals to investigate middle managers’ stressful existence have been made by other scholars (Schlesinger & Oshry, 1984).

Objectives

This study aims to investigate dysfunctional leadership, a pervasive issue in many organisations, that has the potential to significantly erode the internal dynamics of an organisation. This erosion manifests itself in various ways, most notably through the disengagement and disempowerment of middle managers. These individuals, who are crucial to the smooth operation of any organisation, find themselves marginalised and stripped of their power and influence. This disempowerment can lead to a lack of motivation and commitment, resulting in a decline in their performance and productivity.

The costs associated with this disengagement, while not explicitly calculated, are substantial and far reaching. They can have a direct impact on an organisation’s bottom line, affecting revenues and profitability. Moreover, the efficiency of the organisation as a whole can be compromised. This is because disengaged employees are less likely to put in the extra effort that often leads to innovation (Faix, 2023) and improved operational efficiency. They are also more likely to leave the organisation, resulting in high turnover costs and a loss of valuable skills and experience.

Understanding the dynamics of disempowerment is therefore key to improving leadership within an organisation. By recognising the signs of disempowerment and taking steps to address them, leaders can foster a more positive and productive work environment. This involves promoting open communication, encouraging participation in decision-making processes and providing opportunities for professional growth and development. By doing so, they can empower their middle managers, leading to increased engagement, improved performance and, ultimately, a more successful organisation.

Theoretical Framework

The inception of this model is rooted in negative leadership behaviour, a multifaceted issue that can take on various forms. These forms can range from arrogance and abrasiveness to a lack of information flow, all of which contribute to a hostile work environment. This environment can lead to middle managers feeling excluded from decision-making processes, a critical aspect of their roles and responsibilities. This exclusion can engender feelings of disempowerment among middle managers, leaving them unable to influence decisions that directly impact their roles and responsibilities.

When middle managers are subjected to such disempowerment, they may become disengaged from their work. This disengagement is not a monolithic state but can manifest in various forms, including cognitive, emotional, or behavioural disengagement. When managers are disengaged, their performance may suffer, and they may not execute their duties to the best of their abilities. This decline in performance can have an effect on the organisation’s overall performance, leading to reduced revenues, profitability and operational efficiency.

Therefore, it is of paramount importance for organisations to address negative leadership behaviours proactively. By doing so, they can prevent the negative outcomes, fostering a more positive and productive work environment. This approach will not only benefit the individual employees but can also contribute to the overall health and success of the organisation.

Methodology

Data and Participants

Middle-level managers of HR departments attending a leadership development programme for a duration of 12 days spread over a six-month period with multiple interactive sessions were participants in this research. Participants were required to develop stories as part of a learning exercise regarding problems faced by them. The written submissions had to be about problem situations they had faced or had personally witnessed. The details of the people involved in the stories were to be anonymised and the document submitted directly to the faculty organising the training programme. This was to instil faith among the participants that the stories would not go back to the organisation and cause a potential backlash. This was ensured rigorously since the first author was part of the training programme. The assumption in this approach for collecting data was that individuals would like to talk about those themes which were at the top of their mind due to the impact on them.

Analysis

A qualitative analysis (Sharma et al., 2023) of the submitted stories was done to understand the problems documented. For the analysis of these narratives, we followed the following stages:

1. Reading of the stories in their entirety and trying to narrow down on the broad themes the stories convey

2. Reading the stories paragraph by paragraph, looking at the themes within the stories

We focussed on unearthing theoretical concepts (Glaser, 2002), which would allow us to capture the essence of what was happening in the organisation, as perceived through the eyes of the managers. For coding, most qualitative researchers often engage multiple researchers independently coding and then analysing inter-coding reliability quantitatively as a way to demonstrate the rigour of the research process. This, we viewed as an unnecessary quantification of a process which by nature is imaginative and unconstrained (Weick, 1989). In this research, we have adopted the consensus approach, with joint discussions before and during the coding process.

Data Description

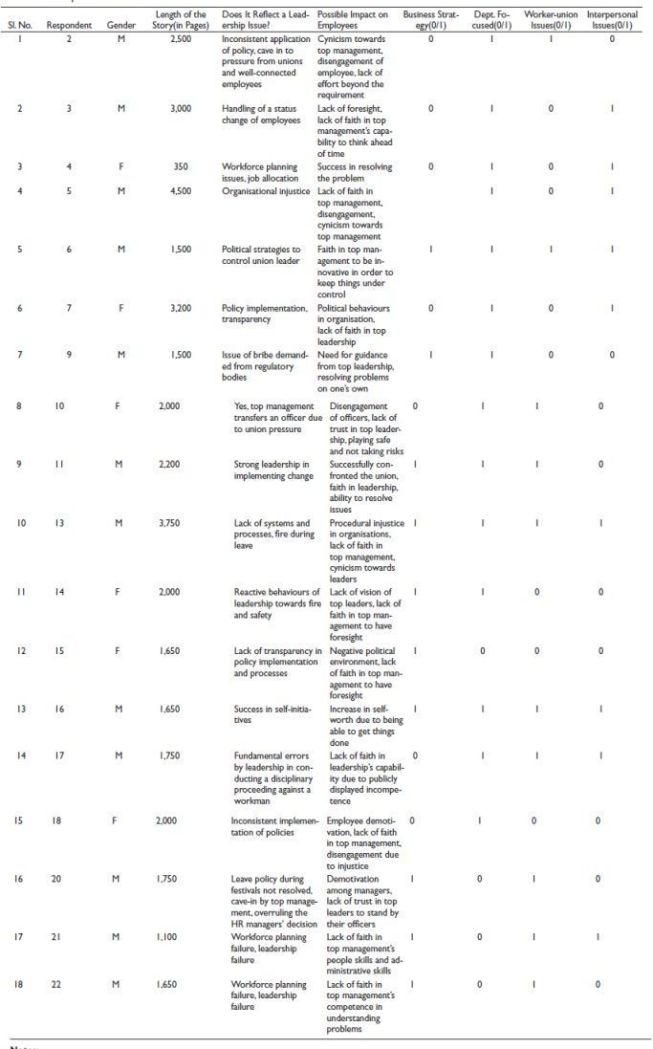

The participants belonged to a single organisation and were from the human resource department. The participants worked in varying locations ranging from plant, regional offices and corporate office. All participants had more than 15 years of experience at the time of the research. From 22 participants, 18 valid stories were obtained in a written format and directly submitted to the faculty. The details of the data along with key initial findings generated from the cases are given in Table 1.

Analysis

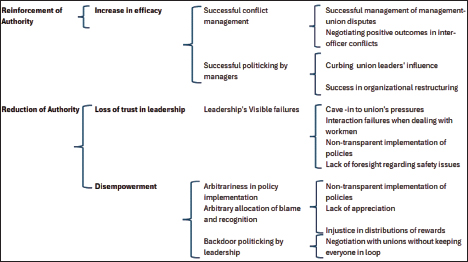

The stories revealed instances of empowerment and positive reinforcement of authority of middle management as well as episodes of disempowerment and dysfunctional leadership. In this article, while we have mentioned the positive episodes, we have focused on the narratives of disempowerment. The same is presented thematically as follows with the thematic map presented in Figure 1.

Successful Conflict Management

Managing conflicts emerges as a significant challenge for the middle managers. These conflicts emerge due to deviant employees, power struggles between unions and the top management and enforcement of policies. These conflicts, for managers, are like moments of truth, episodes wherein they evaluate themselves versus a challenge as well as understand how the top management reacts. Few stories had successful conclusions to conflicts. For example, as illustrated below, a conflict between a supervisor and his subordinate was resolved successfully.

The job [of sales] was not to his liking and nor was of his choice. He had requested [supervisor] for change in role as per his qualifications. But his line manager paid no heed to his request and informed him that the posting was as per the corporation’s requirement.

Table 1. Description of Data and Initial Themes.

Notes:

Figure 1. Thematic Map of Themes Reflected in the Managers’ Narratives

[the subordinate] used to have frequent arguments and disagreements … he was rated poorly on his performance. Hence, he started losing confidence and interest in his job and decided to put in his resignation.

At this juncture Sr. Officials and HR personnel intervened. They had detailed discussions with him … he disclosed that his line manager was an arrogant, rude person and was not an effective team leader. He did not get any support or guidance from him.… Finally, considering [his] aptitude and educational qualification, it was decided to post him in operations, i.e., plant job.

[The subordinate] was relaxed and stress free with the changed role. The output in his performance could be noticed within 2 months.… His engineering knowledge has helped him to bring about new ideas in operations in the plant. (Respondent 4)

Successful management of conflicts is essential for middle managers to be recognised as capable managers within the organisation, but is also part of their well-being in terms of increasing their self-worth and self-efficacy. As the story by Respondent 4 illustrated, being able to intervene successfully implied being able to have influence. In bigger conflicts where consequences of a badly handled situation could hamper the entire plant, for example, when unions threatened the operations of the plant, the behaviour of the top managers exposed their leadership style. Certain managers narrated with pride how they had overcome such threats.

Few of the workmen threatened and nearly assaulted the security men in the plant premises … we also filed a civil suit seeking an injunction to restrain the unions from resorting to strike. Civil court in its order stated that ‘the strike was illegal, and remedies were available within Industrial Disputes Act, 1947 as the proceedings in conciliation were pending’.

Consequent to the implementation of increased work time of 25 minutes by a set of employees, a process of change in mind set of employees has begun and more employees are inclined to come forward and accept the increase in work time on same terms. (Respondent 11)

Backdoor Politicking by Leadership

Along with success stories, there were narratives illustrating cave-ins by top management or explicit bargaining with individuals.

General Secretary of [the union] had a closed-door discussion with GM (HR) … staff [violating the no mobile phone rule] included the son of a family friend of GM (Operations) (Respondent 2)

Rules framed without looking into requirements of the organisation create another set of conflicts. Workers take leaves during the festival season, thus potentially bringing the operations to a halt. A manager’s effort to prevent that was undone by the top management.

All four workmen represented the case to DGM (HR). Each of them explained their position. DGM(HR) called DGM (MFG) and also [HR officer] discussed with them and suggested that their leave may be sanctioned as a special case by taking individual letter from each staff mentioning their reasons and also stating that it shall not be repeated in future.

[HR officer’s protest] ‘if we accede to their request, it would become difficult for the officers to operate plant on festival days’ [was] ignored and bypassed. (Respondent 20)

Successful Politicking by Managers

A story about the top management engaging in a political strategy to control the union leader was written with an apparent sense of accomplishment.

Manager has unofficially guided technical staff on how to form a separate Union. The manager knew that an additional union will reduce the power of the existing union leader...later on, the existing union leader was suspended, and an enquiry initiated against him for physical assault on an officer. Before serving the notice to the union leader, plant manager had informed the local police. (Respondent 6)

A similar story of organisational restructuring conducted in past, over the resistance of union leaders, was narrated with a sense of self-satisfaction, even though there was no personal involvement of the manager.

In spite of the negative reactions from the unions and the old guard of management, the structure was put in place. The new organisation structure [implemented at the shopfloor] was leaner with lesser levels, which gave authority to its staff and independent decision-making. (Respondent 3)

As illustrated in the above vignettes, leadership demonstrated by the top management manifested itself in all the stories in varying degrees. Reflecting good leadership, these narratives indicate something which middle managers looked up to as guidance from the top.

Arbitrariness in Policy Implementation

Dysfunctional leadership manifested itself in multiple ways—cave-in and pressuring subordinates to take decisions counter to what the subordinate considered appropriate (e.g., respondent 20), leading to feelings of disempowerment or cynical views about top management. Such a feeling emerges and is reinforced by a perceived lack of transparency in the implementation of policies or idiosyncratic interpretation and implementation.

Managing equilibrium amongst all the roles of secretaries while arriving the bell-curve was a challenging task for the Moderation Committee. No one could explain to secretaries the reasons for their being labelled as average or underperforming secretaries. (Respondent 7)

The Company has number of HR initiatives, but it is found that the basics of staff motivations are missing as it is perceived there is no transparency in the processes. (Respondent 14)

There was no deduction of Standard Rent Recovery being deducted from [an employee] (Respondent 17)

These along with pressures from connected employees wherein top management give in, or succumb to pressures, creates a situation wherein top management failures become the failures of the HR middle managers, a kind of reflected ignominy.

Leadership’s Visible Failures

Apart from these high-stake conflict situations, top management’s failure in certain routine administrative tasks is another reason for loss of faith among middle managers.

As the above acts of misconduct committed by [an employee] were very grave and serious in nature and also involved misappropriation of cash, he was issued a charge-sheet … [the employee] claimed that since despite his request to record the enquiry proceedings in Hindi, the proceedings have been recorded in English,… In his reply on the findings of Enquiry Officer’s report, [the employee] once again denied the charges levelled against him.

In the labour court it was held that the enquiry proceedings were not fair and were not conducted in accordance with the principles of natural justice and the established law … despite his request to record the enquiry proceedings in Hindi, the proceedings have been recorded in English, he was unable to understand English properly.

Thereafter, no action has been taken by the Management on the nature and quantum of punishment to be awarded to [employee]. (Respondent 17)

Despite leadership failures, certain self-driven initiatives tried out by managers and with successful outcomes were part of managers’ stories.

I have taken so many initiatives like providing cold drinking water, fans, clean toilets facilities and organised health check-up for the contract labour staffs. Also organised football and cricket match between BPCL officials vs. contract labour-staff to build friendly relationship. (Respondent 16)

While the aforementioned vignettes reflected lack of sensitivity and of proactive thinking on behalf of top leaders, certain stories provided concrete examples.

One of operators passed away after a prolonged illness. All the employees wanted to stop production for half a day & attend the funeral. When the message reached Production Manager, he was incredibly angry & in a harsh tone said that production could never be stopped because of year end closing & target to be met.

This immediately infuriated the workers and they gheraoed the office. Ultimately local police were informed to defuse the situation.

He could have managed the situation more diplomatically. Other managers often allow workers to go in batches without disrupting the production. (Respondent 21)

An episode of fire accident in one of the plants provided a glimpse of lack of foresight among top managers.

After the fire episode [fire and safety in-charge] called an urgent meeting of all the officers of his department to discuss performance-related issues … [it was found] that the [previous fire and safety in-charge] had sent a request to HR Department for filling up vacant positions of fire operators.… After a month, HR [had] informed him that their proposal for filling up the [posts] was shot down. (Respondent 14)

The general norm is to rotate staff after a period of 3 years in a particular posting.… There are staff who have completed even more than a decade in their current postings.… a distant relative of General Manager (Operations) continued to be in the procurement department for the last 21 years. (Respondent 10)

Arbitrary Allocation of Blame and Recognition

Stories also reflected the general feeling about justice in the organisation, particularly when it came to fault finding and the need to hold someone accountable.

He [subordinate] narrated the incident to [his reporting officer] that there was a flash fire in on Friday when he [subordinate] was on leave, where a contract worker was injured … [reporting officer] informed that the committee had made some reference regarding him in the report. He said that a caution letter is only a piece of paper and has nothing to do with his performance. But these consolations could not pacify [the subordinate] and he [subordinate] decided to quit the job. (Respondent 13)

A feeling of being neglected and unappreciated was observed in certain stories. Along with these there were stories of certain employees being more privileged than others.

During the presentations to top management of [the department], he was appreciated for his efforts towards resolving all pending separation cases, a few of them pending for more than 6 to 10 years. Despite of working hard, even stretching himself, to ensure that he delivered more than what is expected of him, his incentive payment was far less than expectations. He was also not satisfied with marks given to him and the explanation given for it by management. (Respondent 5)

Discussion

Disempowered as a manager implies that an employee designated as a manager would not be conducting the job as signified by the designation. Such disempowered existence is not a happy situation for individuals, as it implies an undignified existence in the organisation and can lead to negative work-related attitudes and behavioural outcomes (Kane & Montgomery, 1998). Negative leadership behaviours such as arrogance and abrasiveness along with lack of information flow and non-involvement in decisions (Singh, 2006) have been related to employee disempowerment and lack of trust in supervisors. Disempowerment, apart from effects on individuals, has been posited to lead to negative consequences for organisational social capital (Singh, 2006).

Disempowerment, if prevalent in an organisation, would reflect strongly on the quality of the leadership in an organisation. Empowerment has been strongly correlated with top management leadership (Ugboro & Obeng, 2000). Factors like power sharing or refusing the union leaders to cross over the middle managers in decision-making are significant (Bowen & Lawler, 1995), which indicates that despite espoused power sharing, the top management may be interested in status quo. Hardy and Leiba-O’Sullivan’s (1998) views regarding adopting a Foucauldian perspective to understand the complexity and ambiguity of organisational power and interventions by top management possibly interested in perpetuating status quo by using top management discretion and authority provide new research avenues in the meaning of empowerment (power over resources, power over decision-making, power over the meaning given to different situations). Such perspective would identify organisational procedures, hierarchies and reward structures, all of which are designed and maintained by the top management, as impediments of employee empowerment (Psoinos & Smithson, 2002), and thus un-do a manager.

Low autonomy, when manifested in disempowered employees would lead to cynicism and exit among employees (Naus et al., 2007). When employees are bypassed in decision-making, such an organisation would encourage negative political behaviour, which will lead to organisational cynicism (Davis & Gardner, 2004), and lack of involvement in routine tasks as well as organisational citizenship behaviour (Andersson, 1996; Saks, 2006).

This would be in stark contrast to researchers focusing on employees with espoused values of empowerment, which is designed to enable employees to participate in decision-making to minimise employee dissatisfaction and disruptive behaviour within the organisation (Spreitzer & Doneson, 2005). While there has been substantiation talk about self-managed teams wherein many of the functions traditionally reserved for managers become the responsibility of subordinates, including monitoring performance, taking corrective action and seeking necessary guidance or resources (Manz & Sims, 1984), the reality of managers being un-done by the top leadership should temper such ambitious plans. Disempowered managers are likely to be disengaged employees, reflected as cognitive disengagement, emotional disengagement or behavioural disengagement (Andersson & Bateman, 1997), and employees experiencing negative emotions often limit their focus on daily survival (Wollard, 2011). Managerial indifference (Pech, 2009), if widespread, could be a drag on organisational performance, a factor that increases the gap between potential and reality.

‘Distrust in management is pervasive’ is a statement echoed by many scholars (e.g., Pfeffer, 2007). This is, as suggested by our research, due to the multiple instances in which managers are un-done—in front of their peers, subordinates and other corporate witnesses. When their decisions are overturned, or suggestions neglected, they are in a way subject to public humiliation, creating a lack of trust in certain cases and strong cynicism or hostility towards the leaders in other cases. Such lack of trust or cynicism is directed towards both individual leaders (Hall et al., 2004) and organisations. Dean et al. (1998) focus on ‘beliefs, attitudes and behavioural tendencies’ towards an organisation; however, we conjecture that such a negatively oriented energy directed towards specific individual in top management and middle management will not err in painting everyone with the same brush, despite their personality cynicism (Andersson, 1996; Andersson & Bateman, 1997; Byrne & Hochwarter, 2008). Cynicism along with justice is related to employee commitments towards organisational change (Bernerth et al., 2007), which may be a survival issue in highly dynamic environments.

Dysfunctional leadership has been observed to erode the internal dynamics of an organisation (Dandira, 2012; Rubin et al., 2009). This, as obtained by our research, is the cause. The effect is middle managers who end up disengaged and disempowered, as manifestations of dysfunctional leadership. While the costs of such a phenomenon, which results in disengaged and disempowered employees, have not been calculated (Wollard, 2011), it is easy to understand how disengaged employees cost organisations in revenues and profitability, not just by failing to go above and beyond in their productivity but by slow response to managerial situations. Such phenomenon, as it becomes increasingly widespread, creates a high base rate for managerial incompetence (Hogan & Hogan, 2001), leading to deficits in operating efficiency and effectiveness (Balthazard et al., 2006).

Conclusions

The consequences of dysfunctional leadership can have far-reaching and detrimental effects on an organisation’s health, impacting both internal dynamics and overall performance. The specific consequences are not limited to a few dissatisfied employees. Dysfunctional leadership has multifaceted consequences that extend beyond individual employees, influencing the overall performance, financial health and organisational culture. Recognising and addressing dysfunctional leadership is crucial for organisations to foster a positive work environment and ensure sustained success.

Dysfunctional leadership contributes to a negative work environment, leading to disengagement and disempowerment among middle managers (Dandira, 2012; Rubin et al., 2009). Disengaged employees are likely to exhibit reduced commitment, motivation and involvement in their roles, negatively affecting the overall organisational culture. The direct impact of disengagement and disempowerment on organisational performance is significant. While the exact costs have not been quantified (Wollard, 2011), it is evident that these factors can impede an organisation’s ability to achieve its goals and objectives.

Dysfunctional leadership can foster a negative organisational culture characterised by low morale, high turnover rates and a lack of trust among employees. This can create a challenging work environment that hinders collaboration, innovation and the overall well-being of the workforce. Dysfunctional leadership contributes to a high base rate for managerial incompetence (Hogan & Hogan, 2001). Disengagement and disempowerment contribute to a decline in employee commitment, negatively impacting their dedication to organisational goals and values. This erosion of commitment may lead to increased turnover rates and difficulties in attracting and retaining talent. This increased incompetence and talent reduction can cause decline in operating efficiency and effectiveness (Balthazard et al., 2006). Incompetent leadership may lead to poor decision-making, inefficiencies in processes and a lack of strategic direction, further compromising the organisation’s success. This can have direct financial implications, as sluggish responses to managerial situations and reduced initiative may lead to missed opportunities and decreased revenues.

Theoretical Implications

While organisational cynicism has been observed to impact exchange relationship between employees and supervisors (Neves, 2012), we hypothesise that a possibility of cynicism towards organisational leaders would translate into organisational cynicism. Lack of supervisory support would imply employees feeling less motivated to take decisions and engage proactively with problems, merely being content to passing on the problems upwards.

Self-management does not operate in vacuum; it is bounded by multiple external variables (Pech & Slade, 2006). Possibilities of conflict between officers’ concerns regarding their ability to engage productively and authoritatively with deviant employees as well as unions could well clash with the top management’s concern to maintain stability in operations, even at the cost of sacrificing their own officers concerned. Similarly, research in leadership has looked at the leader–member exchange relationship in a narrow perspective (e.g., Gómez & Rosen, 2001) as compared to what we claim here is the broader concern—do the leaders allow their managers to be? Similarly, issues such as employee engagement and organisational support need to be looked at broadly from a manager’s perspective as compared to a limited view (e.g., Ram & Prabhakar, 2011).

Managerial Implications

‘Corporate planners and executives are rarely aware of the deep ideational currents that are continuously at work to constitute the world in which their careers unfold’ (Kilduff & Kelemen, 2001). Is it possible that such a disempowerment is happening unconsciously? We hypothesise that such a possibility may exist, as remnants of older generation managers or of older management styles. What is of danger is to what extent the older style has an influence on organisational policies, reward systems and working styles of employee—if the influence is pervasive, then the efforts towards leadership development down the ranks might have to initiated by examining the policies, systems and working styles. Training programmes would be lower down the list of things to be done.

For career movement, there is a school of thought which links dysfunctional leadership with personality disorders. Personality disorders are hypothesised to be a source of a highly toxic and dysfunctional organisational behaviour (Goldman, 2006; Kahn, 1990), and it would be beneficial for assessing potential leaders on personality disorders before putting on a career track within an organisation. In an organisation which has a compulsory transfer policy, such a policy could be influential in spreading dysfunctional leaders, in a way spreading the disease around.

Limitations and Future Research

This study was conducted on a sample of middle-level managers working in the human resources department. Managers working in production departments or sales departments where the performance of managers are represented in tangible outcomes might have different episodes to discuss, which could have led to additional codes to further enrich the emergent theory of disempowered by leadership.

Despite substantial research which has looked at employee disengagements, employee empowerment/disempowerment, cynicism in organisations and dysfunctional leadership and their relationships with different variables of interest, we think that from a middle manager’s perspective, these are all part of one complete world—a world where their existence as a manager is being denied either totally or eroded away bit by bit by top managers’ leadership style. This might be quite a surprise to most top managers who espouse employee empowerment, leadership development in the ranks and self-managed teams as their very acts are un-doing what they want to have in their organisation.

While organisational cynicism has been observed to impact exchange relationship between employees and supervisors (Neves, 2012), we hypothesise that a possibility of cynicism towards organisational leaders would translate into organisational cynicism. Lack of supervisory support would imply employees feeling less motivated to take decisions and engage proactively with problems, merely being content to passing on the problems upwards.

Self-management does not operate in vacuum; it is bounded by multiple external variables (Pech & Slade, 2006). Possibilities of conflict between officers’ concerns regarding their ability to engage productively and authoritatively with deviant employees as well as unions could well clash with the top management’s concern to maintain stability in operations, even at the cost of sacrificing their own officers concerned. Similarly, research in leadership has looked at the leader–member exchange relationship in a narrow perspective (e.g., Gómez & Rosen, 2001) as compared to what we claim here is the broader concern—do the leaders allow their managers to be? Similarly, issues such as employee engagement and organisational support need to be looked at broadly from a manager’s perspective as compared to a limited view (e.g., Ram & Prabhakar, 2011).

Further research would like to investigate the cost implications of such un-doing. Certain departments like production would be easy to research. It would be of interest to explore the supporting departments such as HR and marketing where there is no tangible output and both dysfunctional leaders and the managers who are in different stages of being un-done can co-exist without raising many concerns.

Persistence of disempowerment is another area of research. What happens when there is change of leadership, from a dysfunctional leader to a positive and genuine leader? How do the leader–member exchanges happen after an episode of horrid leadership style and what is the nature of such exchanges are interesting questions. One would also look at the situation from the new leaders’ perspective—what style or strategy they would have to adopt to get the employees to believe in them? How does that influence the performance of the new leader in a dynamic competitive world—these questions would be of great significance for leaders who seek new challenges in different organisations.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to the anonymous referees of the journal for their extremely useful suggestions to improve the quality of the article. The authors assume the final responsibility for the theoretical appropriateness of the content and the interpretation of the data.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Soumendra Narain Bagchi  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3992-2657

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3992-2657

Andersson, L. M. (1996). Employee cynicism: An examination using a contract violation framework. Human Relations, 49, 1395–1418.

Andersson, L. M., & Bateman, T. S. (1997). Cynicism in the workplace: Some causes and effects. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 18, 449–460.

Balogun, J., & Johnson, G. (2004). Organizational restructuring and middle manager sensemaking. Academy of Management Journal, 47(4), 523–549.

Balthazard, P. A., Cooke, R. A., & Potter, R. E. (2006). Dysfunctional culture, dysfunctional organization: Capturing the behavioral norms that form organizational culture and drive performance. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(8), 709–732.

Batt, R. (2004). Who benefits from teams? Comparing workers, supervisors, and managers. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 43(1), 183–212.

Battilana, J., Yen, J., Ferreras, I., & Ramarajan, L. (2022). Democratizing work: Redistributing power in organizations for a democratic and sustainable future. Organization Theory, 3(1), 26317877221084714.

Bernerth, J. B., Armenakis, A. A., Feild, H. S., & Walker, H. J. (2007). Justice, cynicism, and commitment: A study of important organizational change variables. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 43(3), 303–326.

Bowen, D. E., & Lawler, E. E. 1995. Empowering service employees. Sloan Management Review, 36(4), 73–85.

Byrne, Z. S., & Hochwarter, W. A. (2008). Perceived organizational support and performance: Relationships across levels of organizational cynicism. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23(1), 54–72.

Cioffi, D., Tiller, N., Warnock, L., & Watterston, B. (2024). Learning about and leading from the middle: Stories from three women middle leaders. In E. Benson, P. Duignan & B. Watterston (Eds), Middle leadership in schools: Ideas and strategies for navigating the muddy waters of leading from the middle (pp. 29–41). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Dandira, M. (2012). Dysfunctional leadership: Organizational cancer. Business Strategy Series, 13(4), 187–192.

Davis, W. D., & Gardner, W. L. (2004). Perceptions of politics and organizational cynicism: An attributional and leader–member exchange perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(4), 439–465.

Dean, J. W., Brandes, P., & Dharwadkar, R. (1998). Organizational cynicism. Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 341–352.

Faix, A. (2023). Qualitative innovation in the light of the normative: A minimal approach to promoting and measuring successful innovation in business. IMIB Journal of Innovation and Management, 1(1), 11–24.

Fenton-O’Creevy, M. (1998). Employee involvement and the middle manager: Evidence from a survey of organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 19(1), 67–84.

Fenton-O’Creevy, M. (2001). Employee involvement and the middle manager: Saboteur or scapegoat? Human Resource Management Journal, 11(1), 24–40.

Fernández-Mesa, A., Clarke, R., García-Granero, A., Herrera, J., & Jansen, J. J. (2023). Knowledge network structure and middle management involvement as determinants of TMT members’ ambidexterity: A multilevel analysis. Long Range Planning, 56(3), 102318.

Foss, N. J., & Klein, P. G. (2022). Why managers still matter as applied organization (design) theory. Journal of Organization Design, 1–12. SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4289193 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4289193

Glaser, B. G. (2002). Conceptualization: On theory and theorizing using grounded theory. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 1(2), 23–38.

Goldman, A. (2006). High toxicity leadership: Borderline personality disorder and the dysfunctional organization. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(8), 733–746.

Gómez, C., & Rosen, B. (2001). The leader-member exchange as a link between managerial trust and employee empowerment. Group & Organization Management, 26(1), 53–69.

Hall, A. T., Blass, F. R., Ferris, G. R., & Massengale, R. (2004). Leader reputation and accountability in organizations: Implications for dysfunctional leader behavior. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(4), 515–536.

Hardy, C., & Leiba-O'Sullivan, S. (1998). The power behind empowerment: Implications for research and practice. Human Relations, 51(4), 451–483.

Hogan, R., & Hogan, J. (2001). Assessing leadership: A view from the dark side. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 9(1–2), 40–51.

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724.

Kane, K., & Montgomery, K. (1998). A framework for understanding dysempowerment in organizations. Human Resource Management, 37(3–4), 263–275.

Kilduff, M., & Kelemen, M. (2001). The consolations of organization theory. British Journal of Management, 12(Suppl 1), S55–S59.

Manz, C., & Sims Jr, H. P. (1984). Searching for the ‘unleader’: Organizational member views on leading self-managed groups. Human Relations, 37(5), 409–424.

Martela, F. (2023). Managers matter less than we think: How can organizations function without any middle management? Journal of Organization Design, 12(1), 19–25.

Naus, F., Van Iterson, A., & Roe, R. (2007). Organizational cynicism: Extending the exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect model of employees’ responses to adverse conditions in the workplace. Human Relations, 60(5), 683–718.

Neves, P. (2012). Organizational cynicism: Spillover effects on supervisor–subordinate relationships and performance. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(5), 965–976.

Pech, R. J. (2009). Delegating and devolving power: A case study of engaged employees. Journal of Business Strategy, 30(1), 27–32.

Pech, R., & Slade, B. (2006). Employee disengagement: Is there evidence of a growing problem? Handbook of Business Strategy, 7(1), 21–25.

Pfeffer, J. (2007). Human resources from an organizational behavior perspective: Some paradoxes explained. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(4), 115–134.

Prado, M. C. (2022). The glass jaw: The presence of incivility, conflict, and bullying in disempowering workplaces: A study of middle-level managers in HEIs (Paper 536). [Digital Commons @ ACU, Electronic theses and dissertations]. https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/etd/536

Psoinos, A., & Smithson, S. (2002). Employee empowerment in manufacturing: A study of organisations in the UK. New Technology, Work and Employment, 17(2), 132–148.

Ram, P., & Prabhakar, G. V. (2011). The role of employee engagement in work-related outcomes. Interdisciplinary Journal of Research in Business, 1(3), 47–61.

Rubin, R. S., Dierdorff, E. C., Bommer, W. H., & Baldwin, T. T. (2009). Do leaders reap what they sow? Leader and employee outcomes of leader organizational cynicism about change. The Leadership Quarterly, 20(5), 680–688.

Saks, A. M. (2006). Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(7), 600–619.

Sasaki, I., Kotosaka, M., & De Massis, A. (2024). When top managers’ temporal orientations collide: Middle managers and the strategic use of the past. Organization Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/017084062412366

Schlesinger, L. A., & Oshry, B. (1984). Quality of work life and the manager: Muddle in the middle. Organizational Dynamics, 13(1), 5–19.

Sharma, R., Mishra, N., & Sharma, G. (2023). India’s frugal innovations: Jugaad and unconventional innovation strategies. IMIB Journal of Innovation and Management, 1(1), 25–45.

Singh, J. (2006). Employee disempowerment in a small firm (SME): Implications for organizational social capital. Organization Development Journal, 24(1), 76.

Spreitzer, G. M., & Doneson, D. (2005). Musings on the past and future of employee empowerment. In G. T. Cummings (Ed.), Handbook of organizational development. Sage Publications.

Tarakci, M., Heyden, M. L., Rouleau, L., Raes, A., & Floyd, S. W. (2023). Heroes or villains? Recasting middle management roles, processes, and behaviours. Journal of Management Studies, 60(7), 1663–1683.

Ugboro, I. O., & Obeng, K. (2000). Top management leadership, employee empowerment, job satisfaction, and customer satisfaction in TQM organizations: An empirical study. Journal of Quality Management, 5(2), 247–272.

Weetman, R. (2009). Emergence is not always ‘good’. Emergence: Complexity and Organization, 11(2), 87–91.

Weick, K. E. (1989). Theory construction as disciplined imagination. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 516–531.

Wollard, K. K. (2011). Quiet desperation another perspective on employee engagement. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 13(4), 526–537.

Yang, J., Zhang, Z. X., & Tsui, A. S. (2010). Middle manager leadership and frontline employee performance: Bypass, cascading, and moderating effects. Journal of Management Studies, 47(4), 654–678.