1 Department of Management Studies, DCRUST, Murthal, Haryana, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

This study examines the relationship between meaningful and challenging work, workplace environment and employee engagement. It addresses the dearth of empirical research in this area and utilises Khan’s (1990) model of engagement as the theoretical framework. The research design employed a cross-sectional descriptive approach, with a sample of 981 employees from the IT, banking, telecommunications and education sectors, selected using quota non-probability sampling. A self-reported questionnaire measured the hypothesised relationships between job design characteristics (JDC), workplace environment (WPE) and employee engagement, analysed using structural equation modelling and AMOS. The findings indicate that both meaningful and challenging work and workplace environment significantly impact employee engagement. However, meaningful and challenging work demonstrates a stronger effect (.png) = 0.79, p < .000) compared to the workplace environment (

= 0.79, p < .000) compared to the workplace environment (.png) = 0.24, p < .000) in predicting employee engagement. These results contribute to the academic literature by emphasising the importance of integrating meaningful and challenging work and cultivating a positive workplace environment to enhance employee engagement. The study offers practical implications for HR managers, highlighting the need to focus on job design characteristics and improve the workplace environment to foster meaningfulness in work. By doing so, organisations can enhance employee performance and productivity and reduce turnover intentions.

= 0.24, p < .000) in predicting employee engagement. These results contribute to the academic literature by emphasising the importance of integrating meaningful and challenging work and cultivating a positive workplace environment to enhance employee engagement. The study offers practical implications for HR managers, highlighting the need to focus on job design characteristics and improve the workplace environment to foster meaningfulness in work. By doing so, organisations can enhance employee performance and productivity and reduce turnover intentions.

Employee engagement, job design characteristics, workplace environment, meaningful work, challenging work

Introduction

‘Living for the weekend’, ‘watching the clock tick’, ‘work is just a pay check’.

State of the Global Workplace Report (2022)

According to a Gallup (2022) report, only 21% of the global workforce is engaged and 33% with overall well-being. A majority of employees report that ‘they don’t find their work meaningful, don’t think their lives are going well or don’t feel hopeful about their future’ (State of the Global Workplace Report, 2022). Gallup’s (2017) report resonated the similar experience of Indian employees with low engagement levels. That leaves a lot of room for improvement. People can spend a majority of their lives at work, searching for the purpose of life (Wrzesniewski, 2003). Searching for meaning in one’s life is one of the basic questions of existence. Meaningful and challenging work is well recognised as a significant employee engagement antecedent (Albrecht et al., 2021). As work can have both positive and negative connotations in one’s life, it can be a stressor or dissatisfier, or can lead to burnout, but it can also give meaning, satisfaction and engagement (Wrzesniewski, 2003). It is comparatively easier to manage satisfaction and employee engagement with company policies and initiatives, but meaningfulness being more individual and personal is difficult to manage. Employees obtain meaning through their work. Meaningfulness occurs for short spans of time in an employee’s career, but these moments have a long-term impact on how they perceive their work and their lives. Over the past two decades, research on positive psychology has been on the rise by recognising the importance of employee experience (Linley, 2010; Luthans, 2002). There is a growing focus among scholars and organisations on the relationship between meaningful and challenging work and employee engagement.

Kahn (1990) defined engagement ‘as the harnessing of organization member’s selves to their work roles; in engagement, people employ and express themselves physically, cognitively and emotionally during role performances’. Saleem et al. (2020) argued that people working in a ‘psychologically meaningful and safe environment are more engaged and psychologically available’, therefore establishing a relationship between the workplace environment and employee engagement. According to Crawford (2008), the organisational environment is a vital element for the well-being of the employees at the workplace, which comprises empowering the employees, office layout, managerial style, leader behaviour, participation and assistance. A number of studies grounded on Lewinian Field Theory indicated that organisational environment (climate) has a significant impact on the attitudes and behaviour of employees in organisations (Brown & Leigh, 1996; Noordin et al., 2010; Omolayo & Ajila, 2012; Randhawa & Kaur, 2014; Schneider et al., 1975; Srivastava, 2008). May et al. (2004) found that ‘individuals feel safe when they perceive that they will not suffer for expressing their true selves at work’. ‘Supportive and trust worthy’ behaviour among supervisors and co-workers leads to a perception of safety at the workplace (Edmondson, 1999; May et al., 2004) and enhances an individual’s creativity at the workplace (Deci et al., 1989). Psychological safety at the workplace boosts employees’ engagement and creates innovativeness in such workplace environments (Edmondson, 1996, 1999). Koys and DeCotiis (1991) identified eight subdimensions of psychological climate (PSC), namely, ‘support, recognition, fairness, innovation, autonomy, trust, cohesiveness and pressure’. Nevertheless, meagre empirical research has concentrated on understanding the relationship of meaningful and challenging work and workplace environment with employee engagement. Therefore, the purpose of this article is to examine whether meaningful and challenging work and workplace environment act as critical factors to elucidate the association with employee engagement within the psychological state given in Kahn’s (1990) model.

The article is outlined under the following sections: conceptual framework, hypothesis development, objectives, methodology, results, discussion and conclusions, managerial implications and future research.

Conceptual Framework

Employee Engagement, Job Design Characteristics and Workplace Environment

William Kahn (1990) introduced ‘personal engagement’ based on grounded theory to clear up the intricate issues surrounding employees’ moments of engagement and disengagement from their role performances. His conceptualisation of engagement was based on Goffman’s 1961 role theory, Hackman and Oldham’s 1976 ‘job design characteristics theory’ and motivation theory (Kunte & Rungruang, 2018; Rich et al., 2010; Shuck, 2011). He conceived personal engagement ‘as the harnessing of organization member’s selves to their work roles; in engagement, people employ and express themselves physically, cognitively and emotionally during role performances’.

‘Man’s quest for meaningful work is nothing new, but it has always been left unaddressed’ (Rathee & Sharma, 2019, p. 159), which resonates with the work of Farlie (2011) on psychological meaningfulness and engagement. Jung and Yoon (2016) found that the meaningfulness of work has a significant impact on employees’ job engagement. Van Wingerden and Van der Stoep (2018) revealed that meaningful work positively predicted work engagement and work engagement positively predicted in-role performance.

The workplace environment is an expressive concept and has important extrapolations for understanding employee behaviour in organisational work settings. The concept of ‘climate’ originated with the study of ‘social climates in the workplace’ by Lewin, Lippitt and White in the late 1930s. Lewin (1951) stated that climate ‘is a characterisation of the salient environmental stimuli and is an important determinant of motivation’. Patterson et al. (2004) describe ‘organisational climate’ as the atmosphere of the organisation which is perceived as real by employees within the organisation’s limits and is concerned with innovation, creativity, supportiveness, team climate and progressiveness. The workplace environment comprises ‘supervisors, subordinates, peers, organizational policies and procedures, physical resources of the organisation and other intangible essentials like supportive climate and perceived safety’ for employees, whereby more constructive, creative and positive ideas can emanate (Rana et al., 2014).

Objective of the Study

The objective of the study is to examine the antecedent variables of employee engagement in the service sector in India. The sub-objectives are as follows:

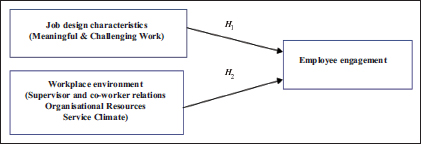

Hypothesis Development

Job Design Characteristics (Meaningful and Challenging Work)

Fletcher et al. (2018) found that the association between perceptions of work context and state engagement was mediated by meaningfulness and availability. Bailey et al. (2019) evidenced the relevance of job design factors such as ‘job enrichment, work role-fit, job content and task characteristics for meaningfulness of work’. Negi et al. (2022) examined engagement predictors and job characteristics such as feedback, skill variety and autonomy, which had a substantial influence on engagement. In line with the above research, it was found that various aspects of meaningful work have been studied, but not much independent research was targeted on the relation between job design characteristics (meaningful and challenging work) and employee engagement. Due to the dearth of research on the above relationship, the researchers hypothesised:

H1: Job design and characteristics (meaningful and challenging work) are positively associated and have a significant impact on employee engagement.

Workplace Environment

Kahn (1990) says psychological safety is enhanced by supportive and trusting interpersonal relationships among employees. May et al. (2004) found that employees perceive meaning in work through satisfying social relations with their co-workers. Co-worker relations stimulate a sense of social recognition and meaning. Demerouti et al. (2001) investigated ‘job resources’ such as ‘performance feedback, supervisor support, job control’ as antecedents of employee engagement. Belwalker and Vohra (2016) argue that favourable conditions at workplace stimulate employees to work hard and achieve organisational objectives. The relationship between an employee and a supervisor has direct implications for their perceived safety at workplace. Bakker and Schaufeli (2015) state that job resources may be different for each organisation for predicting engagement, but ‘opportunities for development, performance feedback, autonomy, skill variety, transformational leadership, justice, and social support from colleagues and supervisors’ are important. Employees are highly motivated and, in turn, are high on engagement if they perceive that the work environment is resourceful (Xanthopoulou et al., 2008). Based on Hanaysha’s (2016) findings, it is evident that both employee engagement and the work environment play a crucial role in shaping organisational commitment. The study highlights that work environment has a significant influence on organisational commitment, underscoring the importance of investigating the association between workplace environment and enhanced employee engagement. Thus, further research is warranted to explore the impact of the work environment on employee engagement and its subsequent effects on organisational commitment.

H2: Workplace environment (supervisor and co-worker relationships, organisational resources and service climate) is positively associated with and has a significant impact on employee engagement.

Methodology

Sample and Procedure

The present study is descriptive in nature as it involved determining the association among the variables and their relationships with engagement and how the already explored variables are influencing the relationships from the perspective of the Indian service industry. A total of 1,200 questionnaires were floated through non-probability quota sampling, with 300 each in the banking, telecommunications, information technology and education sectors. A self-reported questionnaire was administered to employees through both offline and online modes. The study utilised 981 valid responses, for which data was collected from the branches located in Chhattisgarh, Chandigarh, Delhi, Haryana, Maharashtra, Punjab, Tamil Nadu, Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh states of India, with a response rate of 81.75%.

Out of the 981 respondents in the study, 24.7% were from banking firms (n = 242), 24.2% from telecommunications (n = 237), 23.6% from information technology (n = 232) and 27.5% from educational institutions (n = 270), of which 64.1% were male (n = 629) and 35.9% were female (n = 352). A majority of the respondents (n = 407), that is, 41.5%, were between 30 and 40 years of age, 36.3% (n = 356) were between the ages of 20 and 30 years, 13.9% (n = 136) were between 40 and 50 years of age, only 7.8% (n = 77) were between the ages of 50 and 60 years and 0.5% (n = 5) were over the age of 60 years. In terms of educational qualifications, 34.6% (n = 339) had completed graduation, 41.5% (n = 407) were postgraduates and 19.4% (n = 190) had completed a Doctor of Philosophy. With regard to experience, a majority of the respondents (31.2%; n = 345) had been working for 1–years, 25.2% (n = 247) had been working for 5–10 years and 19.7% (n = 193) had been working for 10–15 years in their respective service organisations. Most respondents (41.8%; n = 410) had a monthly income between ₹50,000 and 1,00,000, and 40.2% (n = 394) earned less than ₹50,000 per month.

Measures

Employee engagement was evaluated with ‘Job Engagement Scale (JES)’ items, originally created by Rich et al. in 2010. The scale assessed ‘physical, emotional, and cognitive engagement’ items. The job design characteristics factor was assessed with meaningful work and a challenging work scale. To assess meaningful work, a six-item scale was originally developed by May et al. (2004). A challenging work scale was developed using one item from the Shuck (2010) scale and five items from the ‘Work Environment Inventory’ (WEI), originally established by Amabile & Gryskiewicz (1989). To assess the workplace environment, supportive supervisor relations, rewarding co-worker relations, organisational resources and a global service climate scale were used. The supervisor and co-worker relationships were assessed using a ‘supportive supervisor relations and rewarding co-worker relations’ scale with 20 items. The scale was originally developed by May et al. (2004). The organisational resource scale was originally developed by Salanova et al. (2005). It consisted of 11 items for training, autonomy and technology. Service climate was extracted from Schneider et al. (1998). The participants responded along a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Data Analysis

The sample size for SEM was determined based on previous recommendations from researchers. Research by Yong and Pearce (2013) also resonates with the previous research by Nunnally (1967) and Comrey and Lee (1992), recommending a 10:1 ratio of respondents to variables should be considered for calculating factor analysis. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to check the measurement model for constructing employee engagement as a latent variable and antecedents of engagement: ‘job design characteristics and workplace environment’. The hypothesised relationship between antecedent variables and engagement was measured through SEM. IBM SPSS and AMOS 21 versions of statistical software were used to check measurement models and test structural hypotheses.

Results

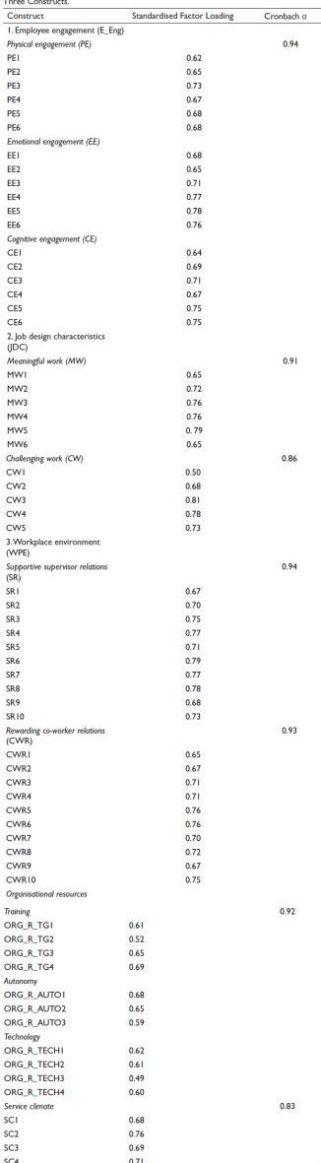

Initially, the individual measurement models were checked using CFA for three constructs as shown in Table 1 (i.e., employee engagement, job design characteristics and workplace environment) before examining the hypothesised structural model. CFA was utilised to evaluate the unidimensionality, construct validity and model fit of the measurement model (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988; Bollen, 1989).

Table 1. Standardised Factor Loadings for the Dimensions and Measurement Items of Three Constructs.

Measurement Model

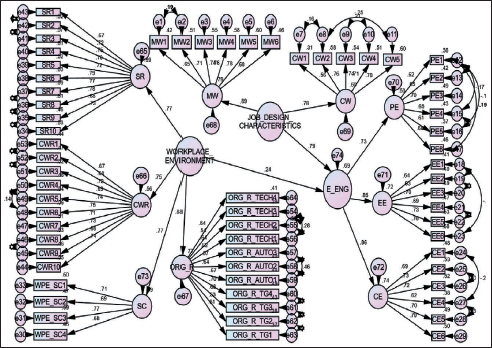

The second-order three-factor measurement model for employee engagement exhibited a strong fit to the data: = (407.303), df = 117, p < .05, / df = 3.48, AGFI = 0.94, GFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.95, CFI = 0.95, NFI = 0.95, RMR = 0.024, PCLOSE = 0.451 and RMSEA = 0.05. Similarly, the measurement model for job design characteristics (meaningful and challenging work) displayed a favourable fit to the data: = (153.006), df = 41, p < .05, / df = 3.73, AGFI = 0.95, NFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.97, CFI = 0.97, RMR = 0.027, RMSEA = 0.05, PCLOSE = 0.289 and GFI = 0.97. Furthermore, the higher-order four-factor model of workplace environment (supportive supervisor and rewarding co-worker relationships, organisational resources and service climate) demonstrated strong fit statistics: = (1828.6), df = 534, p < .05, / df = 3.42, AGFI = 0.90, CFI = 0.93, NFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.92, GFI = 0.90, RMR = 0.039, RMSEA = 0.05 and PCLOSE = 0.564 (Hair et al., 2010, p. 654; Hu & Bentler, 1999). The results align with the accepted standards for model fit, as indicated by CMIN/df values < 3 as acceptable (Kline, 1998) and <5 as a realistic fit (Marsh & Hocevar, 1985). NFI, AGFI, GFI and CFI > 0.95 specify good levels of fit among the data and model, RMR value < 0.09, RMSEA value < 0.05 as good and PCLOSE value > 0.05 indicate good fit (Hair et al., 2010, p. 654).

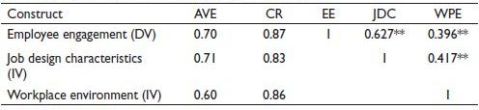

Table 2. Validity, Reliability and Correlations of Constructs.

Notes: AVE, average variance extracted; CR, composite reliability; EE, employee engagement; JDC, job design characteristics; WPE, workplace environment; DV, dependent variable; IV, independent variable; Correlations are significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

Reliability and Validity of Constructs

The three constructs of reliability and validity were established and are depicted in Table 2. The Fornell-Larcker (1981) criterion was utilised to examine the extent of shared variance between latent variables of the model. The present research study assesses the reliability of the construct, that is, CR (composite reliability), which ranged between 0.83 and 0.87, which is more than 0.70 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Maurya et al., 2023) for all the constructs, which specifies the reliability of the data. The AVE obtained for the constructs provides support for convergent validity as the values were above 0.60, indicating 60% or more of the ‘variances in the constructs were explained by their corresponding measures’ (Shuck, 2010).

Hypothesis Testing

The structural model showing the relationship between two second-order measurement models of antecedents of employee engagement, job design characteristics (meaningful and challenging work) and workplace environment (Figure 1), showed a good fit with the data (CMIN/DF = 2.86, p < .001, RMR = 0.08, GFI = 0.80, NFI = 0.85, TLI = 0.89 (approximately 0.90), CFI = 0.89 (approximately 0.90), RMSEA = 0.044 and PCLOSE = 1.00). As shown in Figure 2, an examination of path estimates revealed that job design characteristics (JDC) and workplace environment (WPE) had a significant and positive impact on employee engagement, with a standardised coefficient of βJDC = 0.79, p < .001 and βWPE = 0.24, p < .001, supporting H1 and H2.

Discussion and Conclusion

The present study accepts all the hypotheses that job design characteristics (meaningful and challenging work) and workplace environment have a significant impact on employee engagement, and the results are supported by literature. The results revealed that job design characteristics (meaningful and challenging work) had a more significant and positive impact on employee engagement as compared to the workplace environment. Monica and Krishnaveni (2018) also support the relationship between job characteristics and employee engagement. The empirical results signify the importance of meaningful and challenging work as they provide purpose and zeal in a person’s life.

Figure 1. Proposed Framework of Antecedents of Employee Engagement.

Figure 2. Structural Model Showing the Relationship Between Antecedents of Employee Engagement: Job Design Characteristics and Workplace Environment.

Harter et al. (2003) and Kahn (1990) indicated that easy and routine work can make personnel ‘bored and uninterested’, and over a longer period of time disengaged. Bakker and Demerouti (2008) found that job and personal resources improve employees’ motivational capability when they encounter high job demands. Research also indicated that challenging work requiring professional skills and acclaim from contemporaries are predictors of work engagement in situations of high job demands. Shuck (2010) found that with intermediate and too challenging jobs, employees exerted minimal effort to complete the task. The results reverberated with a study conducted by Britt et al. (2005), who recommended that an adequate level of challenge is a must for in-role performances for maximum effort to be exercised towards goal achievement. Further, Bakker and Leiter (2010) in the study emphasised that employee engagement is positively linked to job demands that are taxing, but it also demands ‘employee’s curiosity, competence, and thoroughness, the so-called job challenges, such as job responsibility, workload, cognitive demands, and time urgency’.

Kahn (2013) identified foundational and relational sources of meaning that impact employee engagement at work and emphasised that the degree to which these sources of meaning are available enables the employee to be fully engaged or not. Jung and Yoon (2016) found that an employee’s meaning of work has a significant impact on their job engagement. Bailey et al. (2019) synthesised the empirical literature on meaningful work and evidenced the relevance of job design factors such as ‘job enrichment, work role-fit, job content and task characteristics for meaningfulness of work’. Job characteristics such as feedback, skill variety and autonomy substantially influence employee engagement and commitment (Negi et al., 2022; Prakash et al., 2022).

The meta-analytic studies by Crawford et al. (2010) indicated a low to moderate linkage among organisational climate and engagement variables. Chandrasekar (2011) found that workplace environment factors such as ‘job aid, supervisor support and physical workplace environment’ significantly affected employees’ performance. Devi (2009) recommended that when employees perceive that their organisation focuses on teamwork, good working conditions, consideration and care for employees, growth prospects, flexibility in work practices and leadership, they are more committed, which is an antecedent to engagement. Demerouti et al. (2001) investigated ‘job resources’ such as ‘performance feedback, supervisor support, job control’ as antecedents of employee engagement. Bakker and Schaufeli (2015) state that job resources may be different for each organisation for predicting engagement, but ‘opportunities for development, performance feedback, autonomy, skill variety, transformational leadership, justice and social support from colleagues and supervisors’ are important. Employees are highly motivated and, in turn, are high on engagement if they perceive that the work environment is resourceful (Xanthopoulou et al., 2008). Hanaysha (2016) revealed that employee engagement and work environment have a significant influence on organisational commitment. It was further revealed that the work environment significantly influenced organisational commitment. Schnorpfeil et al. (2002) described in the study that social support (supervisor and co-worker support) is strongly associated with greater engagement. ‘When employees are engaged, it may be expected that during social interaction at work they will influence their coworkers to behave and feel in a similar way, thus also contributing to a united service climate’ (Salanova et al., 2005, p. 1,218). Hughes et al. (2008) explored the mediation effect of engagement on the association between supportive climate and commitment, which signifies that in a supportive climate, a leader provides an environment of cooperation and support for employees to attain organisational goals. Employees should be equipped with suitable ‘physical, psychological, social, and organizational resources’ which empower the employees to lower the ‘job demands’, to work well and to further enhance their personal growth (Rana et al., 2014).

Managerial Implications

As both the tested hypotheses were accepted, the present study has managerial implications. First, job design characteristics are the most important determinant of employee engagement. The finding suggests that service sector organisations should design jobs that are psychologically meaningful, challenging and enriching (Robbins, 1998), which further create or increase employee engagement. Therefore, organisations desiring to enhance employee engagement should make their employees feel and realise that their work is meaningful, valuable, worthy and contributing to the organisation.

The workplace environment is also one of the significant predictors of engagement. The outcomes of research recommend that organisations need to adequately facilitate employees with organisational resources such as training, technology and autonomy while performing their jobs in the organisation to have an engaged workforce. The study showed that the perception of ‘availability of organisational resources (i.e., training, autonomy and technology)’ at the workplace eliminates hindrances at work and keeps them high on engagement, which indicates a better workplace environment for service. The workplace environment should be flexible, such that employees are encouraged to express their views, take initiative and be innovative. They should be allowed to express their views and inspired to face the criticism with positivity (Kahn, 1990). Therefore, it is important to have a supportive, flexible and safe workplace environment with the necessary organisational and physical resources to have an engaged workforce.

Future Research

Due to the limitations of cross-sectional studies, the researchers can conduct longitudinal research in future research studies to confirm the relationships observed between the variables in the current research study. Future research can make use of multiple sources of data collection to reduce the ‘social desirability response bias’. Repeating this study across other service areas and sectors will be valuable in determining the validity and generalisability of the current findings.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to the anonymous referees of the journal for their extremely useful suggestions to improve the quality of the article. Usual disclaimers apply.

Declaration of Conflicting Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Vandana Sharma  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2013-3989

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2013-3989

Albrecht, S. L., Green, C. R., & Marty, A. (2021). Meaningful work, job resources, and employee engagement. Sustainability, 13(7), 4045.

Amabile, T. M., & Gryskiewicz, N. D. (1989). The creative environment scales: Work environment inventory. Creativity Research Journal, 2(4), 231–253.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411.

Bailey, C., Yeoman, R., Madden, A., Thompson, M., & Kerridge, G. (2019). A review of the empirical literature on meaningful work: Progress and research agenda. Human Resource Development Review, 18(1), 83–113.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2008). Towards a model of work engagement. Career Development International, 13(3), 209–223.

Bakker, A. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2010). Where to go from here: Integration and future research on work engagement. In A. B. Bakker & M. P. Leiter (Eds.), Work engagement: A handbook of essential theory and research (pp. 181–196). Psychology Press.

Bakker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2015). Work engagement. In Carry L. Cooper (Ed.). Organizational behaviour, Wiley encyclopedia of management (Vol. 11, pp.1–5). John Wiley & Sons.

Belwalkar, S., & Vohra, V. (2016). Lokasamgraha: Philosophical foundations of workplace spirituality and organizational citizenship behaviours. International Journal of Indian Culture and Business Management, 12(2), 155–178.

Bollen, K. A. (1989). A new incremental fit index for general structural equation models. Sociological Methods & Research, 17(3), 303–316.

Britt, T. W., C. A. Castro, & A. B. Adler. (2005). Self-engagement, stressors, and health: A longitudinal study. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(11), 1475–1486.

Brown, S. P., & Leigh, T. W. (1996). A new look at psychological climate and its relationship to job involvement, effort, and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(4), 358.

Chandrasekar, K. (2011). Workplace environment and its impact on organizational performance in public sector organizations. International Journal of Enterprise Computing and Business System, 1(1), 1–20.

Comrey, A. L., & Lee, H. B. (1992). A first course in factor analysis. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Crawford, A. M. (2008). Empowerment and organizational climate: An investigation of mediating effects on the core-self-evaluation, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment relationship. Auburn University.

Crawford, E. R., LePine, J. A., & Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 834–848.

Deci, E. L., Connell, J. P., & Ryan, R. M. (1989). Self-determination in a work organization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 7(4), 580–590.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., De Jonge, J., Janssen, P. P., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). Burnout and engagement at work as a function of demands and control. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 27(4), 279–286.

Devi, V. R. (2009). Employee engagement is a two-way street. Human Resource Management International Digest, 17(2), 3–4.

Edmondson, A. (1996). Learning from mistakes is easier said than done: Group and organizational influences on the detection and correction of human error. Journal of Applied Behavioural Science, 32(1), 5–28.

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behaviour in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383.

Fairlie, P. (2011). Meaningful work, employee engagement, and other key employee outcomes: Implications for human resource development. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 13(4), 508–525.

Fletcher, L., Bailey, C., & Gilman, M. W. (2018). Fluctuating levels of personal role engagement within the working day: A multilevel study. Human Resource Management Journal, 28(1), 128–147.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Gallup (2022). State of the global workplace: 2022 report. Gallup. https://www.gallup.com/workplace/349484/state-of-the-global-workplace-2022-report.aspx

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspectives. Prentice Hall.

Hanaysha, J. (2016). Testing the effects of employee engagement, work environment, and organizational learning on organizational commitment. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 229(8), 289–297.

Harter, J. K., Schmidt, F. L., & Keyes, C. L. M. (2003). Well-being in the workplace and its relationship to business outcomes: A review of the Gallup studies. In C. L. M. Keyes & J. Haidt (Eds.), Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived (pp. 205–224). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10594-009

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55.

Hughes, L. W., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2008). A study of supportive climate, trust, engagement and organizational commitment. Journal of Business & Leadership: Research, Practice, and Teaching (2005–2012), 4(2), 51–59. http://scholars.fhsu.edu/jbl/vol4/iss2/7

Jung, H. S., & Yoon, H. H. (2016). What does work meaning to hospitality employees? The effects of meaningful work on employee’s organizational commitment: The mediating role of job engagement. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 53, 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.12.004

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724.

Kahn, W. A., & Fellows, S. (2013). Employee engagement and meaningful work. In B. J. Dik, Z. S. Byrne, & M. F. Steger (Eds.), Purpose and meaning in the workplace (pp. 105–126). American Psychological Association.

Kunte, M., & Rungruang, P. (2018). Timeline of engagement research and future research directions. Management Research Review, 41(4), 433–452.

Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science. Harper and Row

Linley, P. A., Harrington, S., & Garcea, N. (Eds.). (2010). Oxford handbook of positive psychology and work. Oxford University Press.

Luthans, F. (2002). The need for and meaning of positive organizational behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 23(6), 695–706.

Marsh, H. W., & Hocevar, D. (1985). Application of confirmatory factor analysis to the study of self-concept: First-and higher order factor models and their invariance across groups. Psychological Bulletin, 97(3), 562.

Maurya, A. M., Padval, B., Kumar, M., & Pant, A. (2023). To study and explore the adoption of green logistic practices and performance in manufacturing industries in India. IMIB Journal of Innovation and Management, 1(2), 207–232.

May, D. R., Gilson, R. L., & Harter, L. M. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77(1), 11–37.

Monica, R., & Krishnaveni, R.. (2018). Enablers of employee engagement and its subsequent impact on job satisfaction. International Journal of Human Resources Development and Management, Inderscience Enterprises Ltd, 18(1/2), 5–31.

Negi, A., Pant, R., & Kishor, N. (2022). Employee engagement: A study of select service sector organizations using qualitative and quantitative approach. International Journal of Technology Transfer and Commercialisation, 19(2), 177–194.

Noordin, F., Mara, U. T., & Sehan, S. (2010). Organizational climate and its influence on organizational commitment. International Business and Economics Research Journal, 9(2), 1–10.

Nunnally, J. C. (1967). Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill.

Omolayo, B. O., & Ajila, C. K. (2012). Leadership styles and organizational climate as determinants of job involvement and job satisfaction of workers in tertiary institutions. Business and Management Research, 1(3), 28–36.

Patterson, M., Warr, P., & West, M. (2004). Organizational climate and company productivity: The role of employee affect and employee level. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77(2), 193–216.

Prakash, A. S., Gupta, A. K., & Kaur, S. (2023). Economic aspect of implementing green HR practices for environmental sustainability. IMIB Journal of Innovation and Management, 1(1), 94–106.

Rana, S., Ardichvili, A., & Tkachenko, O. (2014). A theoretical model of the antecedents and outcomes of employee engagement. Journal of Workplace Learning, 26(3/4), 249–266.

Randhawa, G., & Kaur, K. (2014). Organizational climate and its correlates: Review of literature and a proposed model. Journal of Management Research, 14(1), 25–40.

Rathee, R., & Sharma, V. (2019). Workplace spirituality as a predictor of employee engagement. In S. Mishra & A. Varma (Eds.) Spirituality in management (pp. 153–168). Palgrave Macmillan.

Rich, B. L., Lepine, J. A., & Crawford, E. R. (2010). Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 53(3), 617–635.

Robbins, S. P. (1998). Organizational behavior concepts, controversies, and applications. Prentice Hall.

Saks, A. M. (2011). Workplace spirituality and employee engagement. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 8(4), 317–340.

Salanova, M., Agut, S., & Peiro, J. M. (2005). Linking organizational resources and work engagement to employee performance and customer loyalty: The mediation of service climate. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1217–1227.

Saleem, Z., Shenbei, Z., & Hanif, A. M. (2020). Workplace violence and employee engagement: The mediating role of work environment and organizational culture. SAGE Open, 10(2), 1–15.

Schneider, B. (1975). Organizational climates: An essay. Personnel Psychology, 28(4), 447–479.

Schneider, B., White, S. S., & Paul, M. C. (1998). Linking service climate and customer perceptions of service quality: Tests of a causal model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(2), 150.

Schnorpfeil, P., Noll, A., Wirtz, P., Schulze, R., Ehlert, U., Frey, K., & Fischer, J. E. (2002). Assessment of exhaustion and related risk factors in employees in the manufacturing industry: A cross-sectional study. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 75(8), 535–540.

Shuck, B. (2010). Employee engagement: An examination of antecedent and outcome variables [FIU electronic theses and dissertations, p. 235]. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/235

Shuck, B. (2011). Integrative literature review: Four emerging perspectives of employee engagement: An integrative literature review. Human Resource Development Review, 10(3), 304–328.

Srivastava, A. K. (2008). Effect of perceived work environment on employees, job behaviour and organizational effectiveness. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology, 34(1), 47–55.

Van Wingerden, J., & Van der Stoep, J. (2018). The motivational potential of meaningful work: Relationships with strengths use, work engagement, and performance. PloS One, 13(6), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197599.

Wrzesniewski, A. (2003). Finding positive meaning in work. In K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline (pp. 296–308). Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Xanthopoulou, D., Heuven, E., Demerouti, E., Baker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2008). Working in the sky: A diary study on work engagement among flight attendants. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 13(4), 345–356.

Yong, G. A., & Pearce, S. (2013). A beginner’s guide to factor analysis: Focusing on exploratory factor analysis. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 9(2), 79–94.