1 Jindal Global Business School, OP Jindal Global University, Sonipat, Haryana, India

2 Indian Institute of Management Shillong, Meghalaya, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

North Eastern Region (NER) of India is largely looked upon as a provider of cheaper and amenable workforce for the business process outsourcing (BPO) industry, with neutral accent, dedication and hospitable behaviour. All these factors make NER a potential BPO destination, further enhanced by different government (central/states) policy initiatives. However, the industry in the regions exhibited an almost flat growth curve over the years, and thus there is a need for understanding the reasons behind the failure of the undertaken policies. This study is largely based on qualitative research on the large information technology and business process management (IT-BPM) industry of India in general and (still) nascent BPO industry of NER in particular. The authors’ understanding and findings are inferred from review of policy documents, numerous data sources and discussions, focus group interviews with national BPO experts, and local BPO entrepreneurs of the region. The impact of coronavirus disease-2019 on the business process management (BPM) industry and the opportunities arising from it, particularly for this region has also been examined. The study presents a set of factors paralysing the industry in NER, and outlines some affirmative measures to rectify the failures. This analysis, though specific to the NER, highlights the issues involved in BPO operations which can be generalised and provide guidelines to other destinations.

BPO policy, North Eastern Region of India, policy analysis, infrastructure, ecosystem

Introduction

In the parlance of business management, minimisation of cost and maximisation of efficiency constitute the core of business optimisation strategies. Since the first Industrial Revolution in Europe, manufacturers and traders have adopted different methods to optimise their scale of operations, endeavouring incurrence of least cost. The practice of outsourcing initially started with the shifting of manufacturing of specific goods to countries with cheaper labour. The crux of this business strategy is fundamentally based on Transaction Cost Economics (Iqbal & Dad, 2013; Singh, 2008), which compares the costs of in-house manufacturing in relation to average costs of buying the same from outside vendors. The practice of outsourcing got further impetus during the second wave of the manufacturing revolution in the 1990s (Sundharan, 2013). Today, it has become a popular management process adopted and intensively applied by various successful organisations across verticals all around the world, and business process outsourcing (BPO) is the most widespread one among its types. Providing significant cost savings, operational flexibility and improved performance are the core tenets of this strategy (Lacity & Willcocks, 2012).

Information technology enabled services (ITES)-BPO service providers are considered as drivers of efficiency and effectiveness. The majority of business processes initially outsourced to nearshore or offshore locations in India comprised back-office operations. Such outsourced operations took advantage of time-zone differences (Mandal & Prasad, 2021) and labour costs. However, there has been an expansion of processes outsourced (Price Waterhouse Coopers [PwC], 2014); voice-based customer support, telemarketing, data processing and conversion, medical transcription, banking finance and insurance services (BFSI) services, e-Governance services, e-procurement and e-commerce, project designing and management, specialised consulting, legal process outsourcing, finance and accounting, and the list goes on. In fact, engineering support offered by BPO players has now extended beyond the traditional areas to digital manufacturing (Infosys Limited, 2016). Gradually, the BPO industry has developed itself into a mission-critical function with utmost importance on specialisation and customer experience management. Innovations in every sector is today happening as drives growth and prosperity (Faix et al., 2023), the same is in the case of BPO-knowledge process outsourcing (KPO) sector globally. The emergence of analytics and business intelligence capabilities owing to the fourth industrial revolution can add a plethora of value-added services and further transform this industry.

There are numerous researches on IT and BPO policies in various Asian and worldwide nations in the body of existing literature (Ahmed & Javed, 2015; Farida et al., 2020; Ramos et al., 2018). However, the majority of research has focused on national BPO policies; none, so far, has looked at the examination of regional BPO policies inside an Asian nation. The North Eastern Region (NER) of India being the significant supplier of skilled manpower for BPO services in the entire India, the ecosystem development in this part of the region is an interesting case for examination. Although there is a huge growth in BPO companies in all parts of India manned by people originating from NER, the NER as a region has not performed well in terms of companies and job creation in the BPO sector. Although there exist dedicated government-level policies brought forward by the central government, the BPO ecosystem picture has not been significantly uplifted. This calls for a study to examine the different policy gaps and barriers that are preventing this region of India from jumping into the BPO bandwagon.

This study provides an explorative qualitative analysis of the BPO ecosystem in North Eastern India. The study attempts to review the existing policy documents and also performs interviews with key internal stakeholders of the ecosystem in this region. The targeted sample for these interviews were entrepreneurs in this region who established BPO setups and also the ones who established and exited from this business due to various hiccups. An attempt is made to investigate the missing blocks that have led to NER not being able to fully capitalise on the human resource strength of this region. Semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions have been conducted with key representatives of BPO companies in eight states for NER and also the public administrators. For the sake of anonymity, the positions or names of either the companies or the public administrators have not been revealed. There have been no prior studies on region-specific BPO or any IT policy of any region in an emerging economy like India, and no policy analysis has been reported in the extant literature. In this context, a first attempt to examine the BPO ecosystem in this region through the lens of BPO business setups and public administrators has been extremely satisfactory in terms of empirical findings. The interviews and focus group discussion were further transcribed, codified and key inferences were synthesised pertaining to the different challenges faced. Based on the inferences obtained, key policy recommendations have been brought forward for enabling NER to reclaim the missed opportunity in the BPO sector.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. The second section provides a brief literature review pertaining to policy analysis in the BPO sector. The third section outlines the methodology used in this study. The fourth section presents a general overview of the BPO industry in the Indian context. The fifth section elaborates on the findings and discussions. The sixth section discusses policy recommendations. The seventh section concludes with a discussion of implications for policy-makers and researchers.

Brief Literature Review

In the extant literature, there have been a lot of studies on IT and BPO policies in different countries globally and in Asian regions. Several studies have been done in different Asian countries such as BPO policy analysis in the Philippines (Ramos et al., 2018), outsourcing policy in Indonesia (Farida et al., 2020), and BPO sector analysis in Pakistan (Ahmed & Javed, 2015), to name a few. The study by Magtibay-Ramos et al. (2008) has explored the input–output analysis of BPO sector in Philippines. The study stressed that if proactive policies are brought in place, and there is ample investment for human capital improvement that this sector would be huge employment generation engine. The study by Madon and Ranjini (2016) has stressed for policy interventions for rural BPO sector in India. Most studies in policy analysis have examined the pan-national BPO policy; and none have explored region-specific BPO policies analysis inside an Asian country.

Methodology

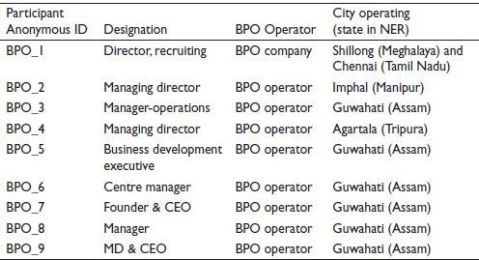

The study is exploratory in nature, making it possible to express many aspects of research and to use the voice of the participants that are not otherwise captured. Qualitative research combined with thematic analysis and quantitative representations through suitable graphical tools are generally used to study the policy impact on ITES/IT sector in different regions globally and in India (Atal Bihari Vajpayee Institute of Good Governance and Policy Analysis, 2021; Kleibert & Mann, 2020; Vajpai, 2023). Data were collected using in-depth interview from 20 participants. Participants were chosen based on their operational visibility in the NER. The representative BPO from Chennai was chosen based on their affirmative response towards analysis of BPO prospects in NER. Participants were BPO companies from all parts of NER and were either operators of the BPO setups in this region or were beneficiaries of the BPO schemes of the government. Before conducting interviews, informed consent was obtained by making the study intentions and goals transparent to the participants. Table 1 provides a sample of the participants that were interviewed as part of this study.

Data were analysed using thematic analysis. The participants were using snowball sampling approach and the number of samples were taken till theoretical saturation was achieved. We have validated the findings by giving to people who experts in this field, and their observation were recorded.

General Overview on BPO Industry: India

The Indian ITES-BPO industry has imprinted its global presence through its world class services across diverse domains since 1990s (PwC, 2014; Singh, 2011; Sundharan, 2013). Their competence in quality and functionality at a significantly lower cost has drawn global acknowledgement as well as investments leading to establishment of large IT-BPO centres – be it global in-house centres or Indian third-party vendors. It has now emerged as a robust industry consisting of top Indian IT software and service giants and other third-party service providers. While cost considerations used to be the primary driver during the initial years, factors such as performance, quality, productivity and rapid technological advancement now play a paramount role (Sundharan, 2013).

Table 1. Basic Profile of the Sample of Participants.

As reported by National Association of Software and Service Companies (NAASSCOM) leadership, the larger IT-BPM industry grew from $177 billion in 2019 to approximately $191 billion as of 2020 globally, recording a growth of approximately 8% annually. It has generated approximately 4.76 million of direct employment. Forty-two of the top 50 global BPOs are currently operating in India and have contributed to approximately 1.1 million jobs in the country. IT-BPM sector accounts for the greatest share in the total services export of India, which is 45% as of the year 2018 (IBEF, 2020).

Findings and Discussions

North East Youth in the BPO Industry: Contributions and Their Vulnerability

The NER of India contributes significantly to the manpower requirement of the ITES/BPM sector of the country. The youth from NER are heavily employed in this sector because of their neutral English accent, hospitable behaviour, and amenable conduct. With hardly any significant presence of the industry in the region, this has led to large-scale migration of NER youths to the rest of the country. To benefit from the availability of such manpower and to mitigate the issues of migration, policy initiatives have been put in place to establish the industry in the region. Several organisations have tried in the past to establish BPOs in NER, and have faced varying degrees of success and failures. Stakeholders such as the Software Technology Park of India (STPI), respective State Governments and the Government of India (GoI) have initiated different policies and incentives to support the setting up of the BPO units in NER. However, the achievements of these schemes till date leave a lot to be desired.

Contemporarily, transitions to newer technologies by the BPO players have culminated in an alarming situation of leaving people ‘technologically unemployed’. Many BPO units are focusing on structural changes towards enhanced flexibility and operational efficiency and eventually turning into product innovation centres (PwC, 2014). The outsourcing industry has reoriented itself from its primarily task-specific and cost-arbitrage model to an innovative and specialised business model (Sherman, 2014). Top employers across the globe are shifting towards computer automation and replacing many back-office workers (especially, call centre agents). In this context, the manpower from NER engaged in this industry (particularly, voice-BPO) across the country can be considered highly vulnerable. There have been discussions on jobless growth in multiple sectors of economy in India (Abraham, 2019); and the same may become true for the BPO sector as well. However, the McKinsey report (Manyika, 2017) highlights that the speed of adoption of automation is not only dependent on the availability of such technologies, but is also inversely proportional to the availably of cost-effective manpower. It thus becomes imperative to bring in better cost structures for the sake of sustainability of the livelihood of this vast BPO workforce, especially those on the lower end of the BPO value chain. With its potential advantages, the NER might just provide the answer.

BPO From NER of India

The history of the BPO industry in NER can be traced back about four decades when a few young entrepreneurs ventured into this segment of the service sector. The pioneers of this industry in NER were SSNetCom (1999) in Meghalaya and Anjaybee Infotech Private Limited (2005) in Assam. Though the industry in the region started not much later than the rest of India, it has not been able to establish itself till date due to major sociopolitical, administrative and other business hiccups.

Till 2015, there was no focused policy or scheme targeting this potential employment-generating segment. The entrepreneurs hardly got any major assistance from the government, and for many, BPO remained a relatively unexplored business venture owing to the absence of an encouraging ecosystem. Consequently, the current status of the BPO industry in NER, unfortunately, presents a sluggish picture as compared to the national scenario. As on date, the IT industry, including BPO and ITES operations, has a very limited existence in NER with only a few private players in selected states. Ironically most of the call centres across major Indian cities have been employing a considerably large number of NER youth. Thus, while contributing directly to the national ITES-BPO industry as a major supplier of the workforce, the region is yet to reap direct benefits from the same.

Advantage of NER for Nurturing BPO Sector

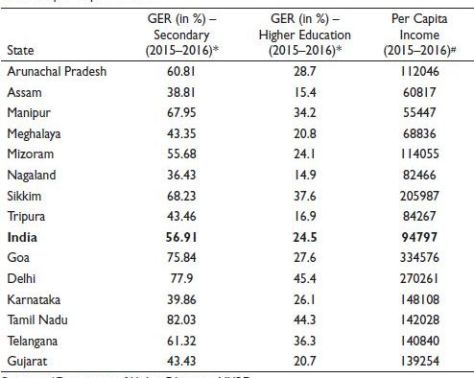

While the region has not been able to march along the rest of the country lagging behind the national average on many economic parameters, it does exhibit at par, and sometimes even superior performance in terms of literacy rates. Among all states and Union Territories (UTs), Mizoram ranked first in literacy as per the 2001 census and third as per the 2011 census with literacy rates of 88.8% and 91.58%, respectively. Other states of NER have also been performing well (Census India, 2011) – Arunachal Pradesh (66.95%), Assam (73.18%), Manipur (79.85%), Meghalaya (75.48%), Nagaland (80.11%), Sikkim (82.20%) and Tripura (87.75%). Only the two states of Assam and Arunachal Pradesh had literacy rates marginally lower than the national average (74.04%). Thus, the entire region is bestowed with sufficiently high literacy rates implying a socially empowered population in the region (Singh, 2018). However, the picture becomes more heterogeneous among the NER states vis-à-vis the forward states of the country when one considers the gross enrolment ratio (GER). Four out of the eight states of the region show a GER lower than the national average in the case of higher education. Table 2 lists the GER and the per capita income of NER states along with some of the top states in terms of their per capita incomes for comparison.

Table 2. GER and per Capita Income of NER States Along with Those of Top States Based on per Capita Income.

Sources: *Department of Higher Education, MHRD.

Note: Bold formatting is applied to India to distinguish it as a country among the listed states.

#Central Statistics Office (CSO).

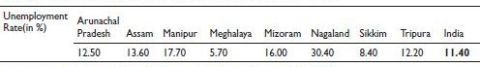

As seen in Table 2, the region houses a relatively literate population, and mostly not too worse off in GER as compared to the national scenario. But the region does not provide enough job opportunities to its educated youth. This culminates in the problem of unemployment in NER. Prolonged underdevelopment, coupled with relatively poor industrialisation and slow employment growth, has led to the unemployment problem in NER (Marchang, 2019). The problem is more prevalent in urban areas for both the sexes in the NER states. Despite employment programmes and policies in the NER, unemployment followed by out-migration for employment and education has been a major issue. As per the employment ratio, except for two states, the states in the regions fall short of the national average (see Table 3). To add to this, in the first quarter of 2020, unemployment soared up to even higher levels due to the coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) crisis.

Table 3. State-wise Unemployment Rates in NER, 2017–2018.

Source: Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No. 1548, dated 1 July 2019.

Note: Bold formatting is applied to India to distinguish it as a country among the listed states.

The BPO industry, which can provide large-scale employment for not-so-highly education/skilled population, can emerge as a possible solution for mitigating the unemployment problem of NER. In fact, the region is envisioned to have a great potential to develop as a back-office BPO hub if properly nurtured. Some of the advantages are highlighted as follows:

The local youths boast commendable proficiency in the English language with low mother tongue influence and are easily trainable for an internationally acceptable accent. Also, the youth of most of the NER states are comparatively more amenable to different cultures and accents.

Due to the above, the training of the human resources from NER for voice-based BPO industry requires relatively half the time as compared to the others from the rest of India.

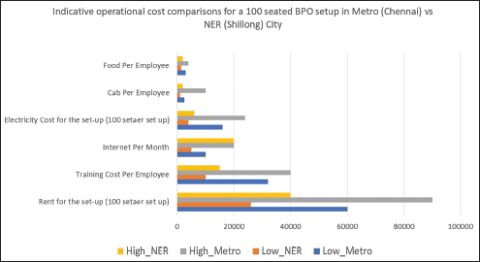

Availability of a large workforce at relatively lesser wage rates and also lower rental costs offers approximately 40% cost advantage. Cost in terms of salary components at various levels of BPO (from entry-level to managerial position) operations are all low in NER. The same is true for other components of expenditure for the industry.

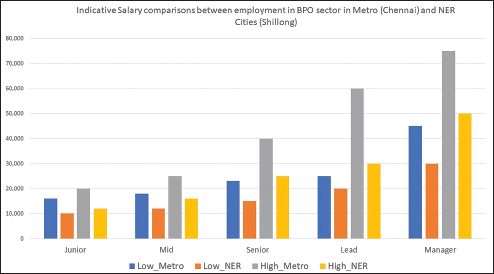

The following figures are intended to draw a cost comparison, prepared from the personal interactions conducted with concerned stakeholders.

The comparison (shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2) is based on discussions and focus group interviews with BPO operators who are operating both in NER as well as other parts of the country, and several domain experts from BPO hubs. The operational cost is computed by considering a BPO unit with the capacity of 100 seats spanning approximately 20 square per seat, and the respective data are again from the same source. Figure 1 and Figure 2 unambiguously reflect the significant amount of cost savings on those parameters for setting up and running BPO units in NER. Further, the following can be additional sweeteners:

Scarcity of alternate job opportunities in the same or other sectors leads to lower attrition rates in the region. The NER youth possesses some key behavioural traits such as sincerity, dedication, and loyalty which to some extent reduces the possibility of recurrent switching of jobs.

Increasing government (central/state) emphasis on skill development and entrepreneurship for the NER youth.

Figure 1. A Comparative Assessment of Indicative Operational Costs (in Rs).

Note: *High NER/metro implies highest average cost (in Rs) and low NER/metro refers to lowest average cost (in Rs).

Figure 2. A Comparative Assessment of Indicative Salaries (in Rs).

Note: *High NER/metro implies highest average salary (in Rs) and low NER/metro refers to lowest average salary (in Rs).

Various fiscal and non-fiscal incentive packages combined with other forms of policy support are offered by both the GoI (under the Digital India programme) and the states, respectively.

Armed with these existing advantages, NER can look forward to exploit the opportunities provided by the robust national IT-BPO industry. There is an emerging trend of expanding towards low-cost Tier II or III cities among most of the established BPO players; the developing cities of NER can turn out to be profitable BPO destinations. The region may be attractive avenue for the following:

Global companies looking for partners to develop shared service centres;

Large Indian BPOs with international customers looking for expansion;

Indian BPOs with domestic customers looking for expansion;

Entrepreneurs looking to serve domestic smaller companies’ outsourcing needs.

Moreover, the present COVID-19 scenario has unleashed a mixed bag of opportunities as well as challenges. Concerns have been raised regarding the post-COVID scenario and policy imperatives. Debates are also going on regarding the chain of positive spillovers generated by this pandemic. These aspects are discussed in subsequent parts.

Policy Interventions in BPO Sector Across India

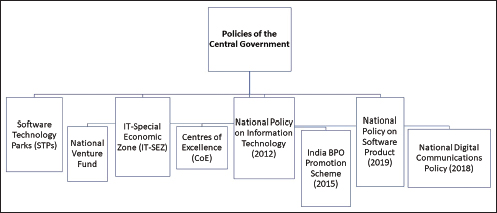

The GoI has introduced several policies and schemes to incentivise the setting of the IT and ITES industry. Major initiatives by the GoIare shown in Figure 3. Schemes/projects specific to NER are aimed at achieving unbiased digital accessibility and uniform regional development in Information & Communication Technology (ICT) infrastructure. Policies are driven towards filling the gaps in different aspects of the IT business life cycle. The BPO promotion schemes have been somewhat a recent announcement, with the previous schemes being targeted for the IT industry as a whole. Policies have been designed to encourage entrepreneurship in this field and thereby to generate employment.

The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) being designated as the nodal ministry for IT-ITES activities, and NASSCOM being a coordinating industry body, have worked in tandem to develop industry-friendly policies.

Figure 3. Major Initiatives by the GoI.

Source: Compiled from GoI websites and reports.

The STPI were formed under the aegis of Department of Electronics and Information Technology as autonomous societies to promote the IT-BPO industry. It was envisaged to promote software exports from the country. Since its inception, STPI is collaborating with the concerned state governments and local authorities to create more space for IT-BPO units with state-of-the-art infrastructure facilities. In 1999, the National Venture Fund was set up to provide venture capital to start up small IT units. Subsequently, IT-special economic zones have been formed as an enabler for infrastructural development, exports, and employment (Singh, 2011). In the year 2012, National Policy on Information Technology was introduced to leverage India’s ICT infrastructure and capabilities, and to create the ecosystem for a globally competitive IT/ITES industry. The specific scheme for enhancement of the BPO sector across the country was ushered in 2015, when the Union Government brought in a scheme named India BPO Promotion Scheme (IBPS). It endeavours to offer an incentive for the creation of 48,300 seats in total in BPO/ITES operations across the country and to create large-scale employment (MeitY, 2019).

NEBPS and Digital North East Vision 2022

With a specific focus on NER, a sister scheme of IBPS was launched as the North East BPO Promotion Scheme (NEBPS) in 2015. Before this, there was no focused scheme for developing the BPO industry in NER, though other industrial promotion schemes have been extant in the region. As a push to the digital resource and capacity scenario of the region, the Digital North East Vision 2022 was also announced in 2017.

The NEBPS aimed at the establishment of 5,000 seats (BPO/ITES operations) distributed across different companies in the region. This also aimed at the creation of approximately 15,000 employment opportunities. It is largely driven by the motive of marketing NER as a prospective BPO destination with its large and educated youth population. Similarly, the Digital North East Vision 2022 envisions to gainfully employ digital technologies to uplift the socio-economic status of people in NER and improve their ease of living. The focus is laid on eight digital thrust areas. This policy also aims to strengthen cyber security and cybercrime norms by establishing some agencies. In addition to these two, there are certain state-specific policies aiming at the development of investment and infrastructure scenarios. Nurturing start-ups and strengthening the IT sector also have found a place in some policies of the NER states.

STPI has been designated as the nodal implementing agency for the NEBPS. As of 2020, there are six functional STPI centres in NER: Aizawl (Mizoram), Shillong (Meghalaya), Guwahati (Assam), Agartala (Tripura), Imphal (Manipur) and Gangtok (Sikkim). Upcoming STPI centres are proposed at Kohima (Nagaland), Silchar (Assam), and Itanagar (Arunachal Pradesh). STPI is helping interested BPO companies with substantial office space, uninterrupted power supply, and bandwidth facilities. In fact, some of these parks in NER houses a select number of BPO companies. Similarly, under the Digital North East Vision 2020, the central government has sought to form North Eastern Regional Computer Security Incident Response Team Cyber Forensic Training Lab, and Cyber Crisis Management Plan for state governments. Under the same scheme, the training of chief information security officers of the state government and its organisation is also being emphasised. Till date, all the NER states have set up cyber forensic training labs under this initiative, though information on other provisions is not readily available. The presence of such infrastructure will help to attract BPO units to the region.

Status of the BPO Promotion Schemes

Under the IBPS, a total of 51297 seats have been allocated under BPO/ITES operations till October 2019. The seats span across 20 states and 2 UTs of the country. Among these, 48,300 are already in functional status. Some of the other new locations other than metro cities where BPO companies have started operations are Srinagar, Madurai, Cuttack, Bareilly, Patna, Tirupati, Kanpur and Wardha (MeitY, 2019).

With the help of NEBPS, the NER-specific BPO scheme, a few BPO companies have commenced their services from some towns of North East such as Guwahati, Imphal, Kohima and Shillong. The evaluation process is undertaken for some other locations namely Majuli, Kokrajhar, Diphu, and Silchar in Assam and Dimapur in Nagaland (MeitY, 2019). However, the two states of Mizoram and Sikkim are still absent from the scene, despite the NEBP Scheme being partially successful in setting up few BPO/ITES companies in the region. Thus, there remains a lot to be achieved under the scheme in an anticipated manner, since the objectives of the scheme have not been actualised completely.

Impacts of COVID-19 Pandemic on BPO Industry

The world was facing its major crisis of the century with the novel coronavirus since its outbreak in China in late 2019. There were large-scale business and social innovations happening as a result of COVID pandemic (Ali et al., 2023). With the adoption of minimal human interaction strategies, there has been an increasing appetite for digital solutions. This augured well for the IT and ITES industry. As a corollary, the outsourcing of business processes was also expected to get a new impetus.

COVID-19 and Its Impact on BPO Industry. At the initial phases, IT-BPO companies were facing increasing pressures due to sluggish demand-supply equations, dampening investments, and dull business sentiment across the globe due to the COVID-19 outbreak. Certain major BPM companies were being forced to halt a large portion of their operations in many countries including India. According to some company executives, the most affected operation was the voice-based one, as compared to the transaction and the platform-based processes. Some companies have faced problems in arranging a large number of computers and internet connections at short notice to enable their employees to work from home. Genpact, one of the largest BPM companies has also expressed concern regarding revenue losses and breaches of client contracts (Pramanik, 2020).

Positive Spill Overs. A set of positive outcomes have also unshackled with the steady adaptation of the businesses with the pandemic. Many industry participants are optimistic that the outsourcing sector will become more relevant and will recover fast once the economic revival begins. The industry players are convinced that behavioural shifts resulting from COVID-19 will help the sector in the long run (Ganesh, 2020).

Human interfaces are being reduced to a great extent and technology has started supplementing many human-centric services/activities. The behavioural change has also accelerated the adoption of technology, opening up new opportunities to move up the value chain. Indian companies may turn towards more tech-led consulting space. It is also predicted that European companies may be more likely to outsource the bulk of their IT or business processes to other countries. Indian IT-BPM can reap large benefits from such activities (Simhan, 2020). IT-BPM companies and technology service providers have also recorded a steep hike in digital transformation deals due to the rising trend of business services going digital due to the impact of the pandemic on the way of life. Major companies such as Infosys, IBM, Accenture, TCS, Wipro, Cognizant, HCL Tech and Genpact have been receiving larger digital transformation projects from their existing as well as new clients (Pramanik, 2020).

Another positive aspect is the rapid digital transformation of businesses. Most of the brick-and-mortar businesses in India have suddenly realised the importance of digitalisation and are transforming themselves into digital businesses. One of the key supporting pillars of digital business is customer support, most of which is voice-based (Pramanik, 2020).

There is another silver lining. Though hiring activities initially recorded a steep fall, the BPM firms are now recruiting more employees as demands for customer support services have increased drastically with online transactions regaining momentum among consumers during the lockdown phases (Pramanik & Chandrashekhar, 2020).

Scenario in NER of India. At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, most of the BPO companies started laying off a major proportion of their employees to ensure business continuity by minimising costs. This has resulted in a major proportion of the NER talent pool working in this sector losing their livelihoods. Already lacking in job opportunities, NER might be hard-pressed to provide this retuning population with alternate employment.

At the same time, there exists an underlying positive perspective. With new opportunities in voice-based BPO, and with industry-trained and experienced manpower available in abundance, NER is now, more than ever, in a position to usher in a BPO revolution. Concerns of being away from home in the face of a pandemic, gainful employment near home may appear to be a lucrative option for a major section of returnee BPO employees of NER. This also provides an opportunity for the established BPO players in the rest of India to cut costs and relocate their units, at least some part of those, in the region. However, this will require the respective state governments to quickly pitch in and spread the red carpet.

Policy Recommendations

As stated earlier, it is not that entrepreneurs have not attempted to cash in on the idea of setting up BPO operations in the region. Attempts were made mostly in few cities in NER by entrepreneurs but without expected success. Solely having neutral accented manpower in abundance might not incentivise the industry enough to look at NER. This requires developing the overall BPO ecosystem.

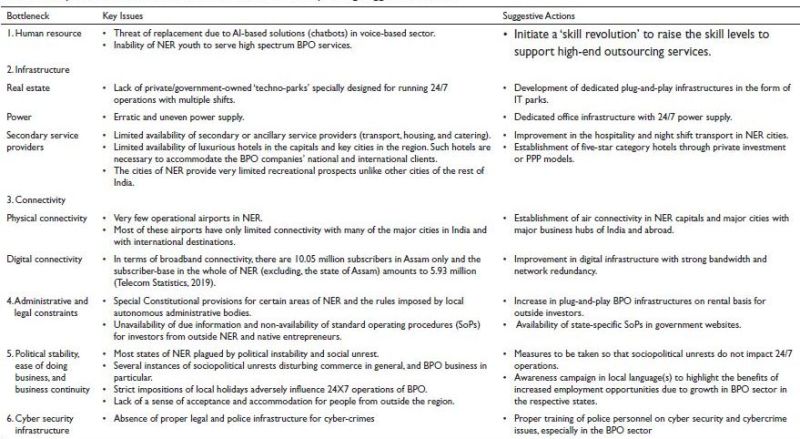

The ecosystem needs to provide for a range of other factors. A closer review of the status of the BPO sector (as shown in Table 3) reveals shortcomings in NER as compared to Tier II/III cities in other states of India in terms of infrastructural deficiencies, restraints in business operation, and human resource issues. Though a weak infrastructure and poor connectivity are often cited to be the most obvious inhibitors, other factors such as managerial deficiencies, dull business ambiance, sociopolitical quirks, and absence of a workforce with advanced skill-set also constitute major challenges.

Further, the BPO industry in its 40 years existence in India has largely staffed voice-based operations, and a substantial contribution to the workforce came from NER. However, two factors have transformed the dynamics: (i) the movement of the voice-based BPO operations to other low-cost destinations like the Philippines (Kabiraj & Sinha, 2017) and (ii) the advent of artificial intelligence (AI) and automation of voice-based operations. These two are squeezing out the opportunity-window for the voice-based BPOs moving to NER.

Policy Gaps in the Context of NEPBS

The BPO promotion Scheme for NER, NEBPS, envisages to provide viability gap funding in the form of financial support amounting 50% of expenditures towards CapEx and/or OpEx, with a cap of ₹ one lac per seat (MeitY, 2019). However, there are issues associated with the scheme as faced by the current and prospective BPO operators.

During discussions and focus group interviews, several entrepreneurs have expressed concern about the lack of information dissemination regarding timelines of the procedures involved to apply for the scheme. The structure of incentives of the scheme has also been criticised by some stakeholders. Incentives are currently tied to the infrastructure setup, and with newer technologies like cloud now being available, a BPO unit functioning at a different location planning to set up a unit in NER may want to take advantage of cloud setup to reduce infrastructure cost at its different units. This issue may be tackled by reorienting the policy toward output-based subsidy, possibly in terms of the number of jobs created. This would also encourage the long-term economic viability of the already established enterprises or prospective ventures.

It is also noteworthy that the success of the scheme in terms of the units set up (because of the intervention of the scheme) is not very appreciable. The scheme, launched in the year 2015, has set up a total of 2051 seats across 30 units with the given set of incentives. However, one or two major BPO providers would have surpassed this number in a very short time, provided they were enticed and incentivised by a supporting operating ambiance. The NEBPS scheme can thus be more important for the local players requiring handholding for setting up their units, rather than to lure bigger units operating in the rest of India locations to set up shop in this region. But the pre-requisites such as a minimum 25 seats, a minimum average annual turnover during a stipulated period, and the like, stand in the way of small local entrepreneurs. Further, discussions and focus group interviews with local entrepreneurs brought out that the single major issue faced by them is customer acquisition.

Harnessing the Potential of BPO Industry in NER

Unlike other countries such as France, Italy, Spain and many others, where the BPO centres function from remote locations, the BPO sector in India has been concentrated around a few big cities. Given the cost advantages, there is an increasing interest among the established BPO players towards the emerging Tier II and III cities. In this context, NER can possibly board the BPO bus, this being incumbent on a comprehensive strategy to mitigate the issues discussed in the earlier section.

There is an increasing push towards chatbots in customer support, at least at the preliminary stages, which was traditionally taken care of by the voice-based BPO workers. This is because of the increasing cost of the latter. The chatbots, however, leaves much to be desired. While these chatbots will improve their performance with time through machine learning, the availability of cheap and professional manpower will disincentivise the adoption of such technologies. In this regard, NER provides a possible solution with its cost and other advantages, provided the irritants are ironed out.

The way forward as suggested by the experts during discussions and focus group interviews can be summarised as follows:

Setting up of plug-and-play infrastructure with adequate bandwidth and power supply assurances.

Creating a single-window clearance system to take care of the legal hassles related to setting up of new units.

Plugging the gaps in cybercrime-related law enforcement and strengthening the administrative and legal support system.

Setting up of training centres to skill the local youth so as to provide industry readier manpower. In addition, reskilling the lateral workforce for advanced levels of services is also required to adapt to the recent trends.

Relook at the possibility of converting the subsidy through NEBPS to an output-based one.

A precondition to attract larger players is to have a local ecosystem. Thus, it is important to have successful local entrepreneurs in the BPO space. Thus, in addition to the subsidy, it is important to help them in customer acquisition. Towards this, a similar setup as is done for agri-marketing can be considered; that is an agency that can help connect the local BPO units with the customers across the globe.

As seen in Table 4, major weakness and corresponding suggestions are being outlined in a cohesive manner:

Table 4. Key Bottlenecks for BPO Sector in NER and Corresponding Suggestive Actions.

Conclusions

Enjoined by its gradually developing Tier II/III cities, NER can claim its pride of place in the nation’s BPO space, given the right set of initiatives and policies being designed and implemented in a timely manner. Imbibing enthusiasm among local entrepreneurs and attracting both global as well as national BPO players will help NER to attain the much-needed economic growth. The current pandemic has made the region more fertile for such an initiative.

Given the current opportunities, provisions of single-window clearance system to support incoming BPO units seem to be an immediate requirement. Going ahead, setting up of plug-and-play systems under IT parks will address the four major challenges of sufficient real estate availability, dedicated Internet Broadband connectivity, incessant power supply, as well as legal and administrative challenges faced by BPO units in the region. These will also sort out the issue of political uncertainties to a certain extent. Such facilities will also reduce the pressure on policing infrastructure, as the specialised cybersecurity expertise requirements will get localised. A certain number of IT parks are already functioning in the region, and temporary provisions may be looked into to take care in case of increased demand.

Respective governments will need to assess the existing set of initiatives and reorient them as per the needs for proper orientation of the enabling policies. Formation of government-sponsored entities can be a way forward for supporting local BPO players in customer acquisition. STPI can also pitch in for marketing of the sector in NER. A focused BPO policy, both at the central and state levels, separate from existing IT policies can be a major step to encourage the sector and provide confidence to the investors.

In the longer run, reskilling and upskilling of the BPO workforce with the upcoming changes in the BPM industry will be required to avoid their obsolescence and resulting unemployment. In this context, a prominent role can be played by the educational institutes (general, technical, and others) in the region, and may be incentivised to tune some of their offerings toward the demands of transforming the BPO industry.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the anonymous referees of the journal for their extremely useful suggestions to improve the quality of the article. Usual disclaimers apply.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Biplab Bhattacharjee  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3886-8409

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3886-8409

Abraham, V. (2019). Jobless growth through the lens of structural transformation. Indian Growth and Development Review, 12(2), 182–201.

Ahmed, R. R., & Javed, S. H. (2015). Business process outsourcing: A case study on Pakistan’s OutBound call centers. Journal of Resources Development and Management, 11, 75–81.

Atal Bihari Vajpayee Institute of Good Governance and Policy Analysis. (2021). Assessment of IT/ITeS industry in Madhya Pradesh: A study to develop investment friendly state IT policy. https://aiggpa.mp.gov.in/uploads/project/N_112_1632384357891.pdf

Ali, E., Malik, M., & Satpathy, S. (2023). Exploring the phases and measuring the effectiveness of social innovations waved during coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: Implications from India, IMIB. Journal of Innovation and Management, 1(2), 113–146.

Census India. (2011). State of literacy. In Provisional population totals: India. https://www.educationforallinindia.com/chapter6-state-of-literacy-2011-census.pdf

Faix, A. (2023). Qualitative innovation in the light of the normative: A minimal approach to promoting and measuring successful innovation in business. IMIB Journal of Innovation and Management, 1(1), 11–24.

Farida, I., Setiawan, R., Maryatmi, A. S., Juwita, M. N., & Muqsith, M. A. (2020). Outsourcing policy in Indonesia. American Research Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences, 3(10), 26–31.

Ganesh, V. (2020, April 13). Post COVID-19, IT-BPO players see new business opportunities. The Hindu Business Line. https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/info-tech/post-covid-19-it-bpo-players-see-new-business-opportunities/article31333067.ece

IBEF. (2020). It and BPM. India Brand Equity Foundation. https://www.ibef.org/download/IT-and-BPM-July-2020.pdf

Infosys Limited. (2016). Industry 4.0-as-a-service: BPO solutions in the age of digital manufacturing. https://nearshoreamericas.com/industry-40asaservice-bpo-solutions-usher-age-digital-manufacturing/

Iqbal, Z., & Dad, A. M. (2013). Outsourcing: A review of trends, winners and losers and future directions. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 4(8), 91–107.

Kabiraj, T., & Sinha, U. B. (2017). Outsourcing under incomplete information. Indian Growth and Development Review, 10(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1108/IGDR-03-2017-0014

Kleibert, J. M., & Mann, L. (2020). Capturing value amidst constant global restructuring? Information-technology-enabled services in India, the Philippines and Kenya. The European Journal of Development Research, 32(4), 1057–1079.

Lacity, M. C., & Willcocks, L. P. (2012). Advanced outsourcing practice. In M. C. Lacity, L. P. Willcocks & S. Solomon (Eds), Robust practices from two decades of ITO and BPO research (1st ed., pp. 1–24). Palgrave Macmillan.

Madon, S., & Ranjini, C. (2016). The Rural BPO Sector in India: Encouraging inclusive growth through entrepreneurship. In B. Nicholson, R. Babin & M. C. Lacity (Eds), Socially responsible outsourcing. Technology, work and globalization. Palgrave Macmillan.

Magtibay-Ramos, N., Estrada, G., & Felipe, J. (2008). An input–output analysis of the Philippine BPO industry. Asian-Pacific Economic Literature, 22(1), 41–56.

Mandal, B., & Prasad, A. S. (2021). A simple model of time zone differences, virtual trade and informality. Indian Growth and Development Review, 14(1), 81–96.

Manyika, J. (2017). Technology, jobs, and the future of work. McKinsey Global Institute, McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Featured%20Insights/Employment%20and

Marchang, R. (2019). Youth and educated unemployment in North East India. IASSI Quarterly, 38(4), 650–666.

Meit, Y. (2019). Ministry of electronics and information Technology Annual report 2019. Government of India. https://www.meity.gov.in/writereaddata/files/MeiTY_AR_2018-19.pdf

Outsource2India. (2020). The outsourcing history of India. https://www.outsource2india.com/why_india/articles/outsourcing_history.asp

Pramanik, A. (2020, August 10). IT, BPM companies see a sharp rise in digital transformation deals. The Economic Times. https://m.economictimes.com/tech/ites/it-bpm-companies-see-a-sharp-rise-in-digital-transformation-deals/amp_articleshow/77449321.cms

Pramanik, A., & Chandrashekhar, A. (2020, August 11). Revival in e-commerce demand leads to increased hiring at BPM firms. The Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/ites/revival-in-e-commerce-demand-leads-to-increased-hiring-at-bpm-firms/articleshow/77396858.cms?from=mdr

Price Waterhouse Coopers (PwC). (2014). India: A destination for sourcing of services PwC perspective. https://www.pwc.in/assets/pdfs/publications/2014/india-as-a-destination-for-sourcing-of-services.pdf

Ramos, N. M., Estrada, G., & Fellipe, J. (2018). An input–output analysis of the Philippine BPO industry. Asian-Pacific Economic Literature, 22(1), 41–56.

Sherman, R. (2014, August 6). Innovation and BPO: ‘A way of doing business’ mindset. https://www.capgemini.com/2014/08/innovation-and-bpo-a-way-of-doing-business-mindset/

Simhan, R. (2020, April 8). Indian IT sector may take a heavy hit as covid betters US and Europe. The Hindu Business Line. https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/info-tech/indian-it-sector-may-take-a-heavy-hit-as-covid-batters-us-and-europe/article31289747.ece

Singh, N. (2008). Transaction costs, information technology and development. Indian Growth and Development Review, 1(2), 212–236. https://doi.org/10.1108/17538250810903792

Singh, K. (2018). Literacy rates in North East India - An analysis. International Journal of Research in Social Sciences, 8(11), 214–222.

Singh, P. K. (2011). Problems and prospects of business process outsourcing in India since 1990. Shodhganga. http://hdl.handle.net/10603/246897

Sundharan, S. (2013). Structure, growth and performance of Indian IT-BPO industry. International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management, 1(2), 1–17.

Vajpai, I. (2023). Role of the Indian IT sector in attainment of the SDGs: A qualitative study [Conference paper]. https://ic- sd.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/2023-submission_411.pdf