1Department of Management Studies, Central University of Haryana, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

This research paper aims to identify and structure the enablers that promote organisational inclusivity, fostering a workplace that values diversity and inclusion. Using Interpretive Structural Modelling (ISM), the study identifies the following four clusters of enablers: autonomous, linkage, dependent and driving. Furthermore, the research findings suggest that inclusive leadership acts as a key driving factor for promoting inclusivity in the organisation. The study offers practical implications for human resource managers to develop targeted strategies to create an inclusive culture and enhance overall organisational performance by recognising and prioritising the identified enablers.

Organisational inclusion, Interpretive Structural Modelling (ISM), enablers, inclusive leadership

Introduction

Organisations are increasingly recognising the importance of diversity and inclusiveness in today’s global business landscape. Inclusivity is not just a buzzword, but a strategic foundation for success in a dynamic and interconnected world. It fosters innovation, adaptability and competitive advantage in diverse markets (Brimhall et al., 2018). Embracing diversity is now a critical imperative for sustainable human resource management (Gehrels & Suleri, 2016). The recognition of the significant role played by an inclusive environment is underlined by its power to inculcate a sense of belonging, spark creativity, drive innovation and improve overall performance (Naseer et al., 2023; Nguyen et al., 2022; Sabharwal, 2014). Despite the growing recognition of organisational inclusivity, many organisations struggle to turn inclusive ideals into actionable practices that empower all employees (Theodorakopoulos & Budhwar, 2015). Achieving organisational inclusion goes beyond merely assembling a diverse workforce; it necessitates an ecosystem where every individual, regardless of their background or experiences, feels appreciated, respected and empowered to contribute to the organisation’s vision and mission (Jain, 2020). It involves recognising and celebrating individual perspectives and combating biases. Many studies have shown that an inclusive workplace matters to the organisation’s effectiveness (Brickson, 2000; Cox, 2001; Davidson, 1999). Thus, managers and leaders need to address the fundamental enablers of inclusion to unlock the potential of diversity. This will result in a series of research questions: (a) What are the important factors that drive a more inclusive environment in the organisation; (b) How do these identified enablers interrelate within the organisational context; (c) What components constitute a comprehensive structural model capturing different enablers responsible for organisational inclusivity; (d) How can the identified enablers be categorised as anonymous, linkages, dependent or independent?

Fostering a diverse and inclusive environment requires leadership commitment, staff development, inclusive policies and accountability measures (Jadaun, 2018). Simultaneously, factors like job match, policy adherence, accommodation and public support are also crucial (Johnsen et al., 2022). Leaders need empathy, patience and a non-judgemental attitude for effective inclusion (Johnsen et al., 2022). Further, diversity, equality and inclusion (DEI) practices, include training, diversity councils, varied hiring and mentorship programs (Nautiyal, 2018). In Indian SMEs, inclusive work culture is influenced by the work environment, institutional culture, employee involvement in decision-making and demographic background (Bhanu, 2022). This shows that while organisational inclusion and its enablers have been extensively studied, the intricate relationships between them remain unexplored. Existing studies focus on individual enablers, but this research uses Interpretive Structural Modelling (ISM) to create a structured framework that shows how enablers affect an inclusive workplace. A comprehensive literature review will identify organisational inclusion facilitators and examine their links using ISM. The research will also classify these facilitators by their influence and interdependence level, revealing their relative importance in organisational inclusion.

The paper unfolds systematically, with each section contributing distinct insights. The second section provides context for existing studies. After that, the third section describes the methodology. The fourth section details model development. The study’s conclusion and discussion are in the fifth section. Next, the research paper discusses managerial implications. Finally, the paper concludes with the limitations and future research directions.

Literature Review

This study identified eleven enablers of organisational inclusion through literature review and expert advice, leading to an ISM model based on a relationship matrix.

Workplace Culture/Climate

Workplace culture shapes organisational dynamics and employee experiences through a complex interplay of beliefs, values and shared meanings. It fosters belonging and identity, operating at a deeper level of unconscious assumptions (Schein, 2004). There is a profound link between organisational culture and leadership which empowers leaders to influence fundamental norms and values (Jaskyte, 2004; Schein, 1992). Hagner (2000) recognised the significance of workplace culture and created the workplace culture survey as a mechanism for evaluating and comparing individuals’ levels of inclusion within different workplace environments. Positive and inclusive workplace cultures, as highlighted by Findler et al. (2007), promote belonging, psychological safety and authentic expression, driving engagement and commitment.

Organisational Policies and Practices

Organisational policies and practices serve as formal guidelines and rules that demonstrate an organisation’s commitment to DEI. It is crafted to ensure fairness, inclusive policies offer equal opportunities, fostering a valued and respected environment for all employees. Janssens and Zanoni (2008) highlight the importance of inclusive policies that promote equitable treatment and recognise individual differences. Gallegos (2013) underscores explicit guidelines, rules and policies for respectful interaction. Focused and sharp policies build a strong foundation for DEI. Policies related to maternal leaves, education, health and equitable payment lay the foundation for an inclusive culture (Khan, 2023).

Effective Communication

Effective communication fosters inclusivity by promoting transparency, open interactions and value for all voices. It encourages diverse perspectives and active listening, promoting collaboration and valuable contributions. Janssens and Zanoni (2008) emphasises communication’s role in fostering inclusivity, with Tang et al. (2015) and Shore et al. (2011) highlighting collaborative initiatives that involve the exchange of information and diverse perspectives. Transparent discussions and leadership’s feedback is crucial for organisational inclusion (Davidson & Ferdman, 2002; Daya, 2014; Ferdman et al., 2010). Furthermore, individuals need information, informal networks and resources for proficient job performance (Mor Barak et al., 1998; Pelled et al., 1999).

Training and Education

Diversity and inclusion-related training and education enhance cultural competence, addressing unconscious biases. It empowers individuals to foster inclusivity, interact effectively with diverse colleagues and cultivate crucial behaviours for organisational inclusivity. Offerman and Basford (2014), highlighted that leaders should prioritise such training to cultivate inclusive behaviours. Training in implicit bias and inclusive leadership skills is crucial for leaders to foster an inclusive work culture (Higginbotham, 2015). This training equips them with the ability to be reflective and responsive to feedback, fostering a more inclusive and supportive leadership style.

Employee Resource Groups (ERGs)

Employee resource groups (ERGs) in organisations support minority employees, offering social networks, resources for development and connections with executives, demonstrating commitment to equity and inclusivity (Dennissen et al., 2020; Douglas, 2008; Friedman & Holtom, 2002; Welbourne et al., 2017). They serve as inclusive business strategies, providing opportunities for expression, information access, interactions, contribution and advancement (Douglas, 2008).

Inclusive Leadership

Inclusive leadership shapes organisational culture by promoting diversity, fostering learning and enhancing performance (Boekhorst, 2015; Booysen, 2013; Cottrill et al., 2014; Gallegos, 2013; Henderson, 2013; Wasserman et al., 2008). Leaders who exhibit inclusive behaviours create psychological safety, increase employee engagement in innovative tasks, enhance unit performance and elevate work engagement (Carmeli et al., 2010; Hirak et al., 2012; Nembhard & Edmonson, 2006). This approach values diverse perspectives, empowers employees and improves organisational outcomes.

Conflict Resolution Mechanisms

Conflict resolution mechanisms in organisations aim to address conflicts fairly by considering diverse perspectives, avoiding biases and fostering collaboration among employees. Research by Roberson (2006) emphasises the importance of inclusive practices, such as creating collaborative environments for resolving conflicts and involving underrepresented groups in decision-making processes.

Work–Life balance

Prioritising work–life balance in organisations enhances employee well-being, job satisfaction and productivity. Deloitte’s Australia Research Report (Deloitte, 2012) identifies work–life balance as a key enabler of inclusion, alongside merit-based practices and organisational policies. Supporting work–life balance is a key factor in fostering inclusion and organisational success (Aysola et al., 2018). Organisations should create environments that support employees in managing personal and professional commitments effectively.

Mentorship and Sponsorship Programs

Mentorship and sponsorship programs offer guidance and advocacy for employees, aiding career development and promoting diversity and inclusion (Hill & Gant, 2000; Hu et al., 2008; Thomas, 1990). Cross-cultural mentoring fosters interactions between diverse individuals, while sponsorship supports underrepresented employees, though lacking the mutual benefits of mentorship (Johnson-Bailey & Cervero, 2004). Integrating these initiatives into broader diversity and inclusion strategies enhances organisational support for all employees (Bohonos & Sisco, 2021).

Inclusive Hiring/Recruitment Practices

Inclusive hiring practices aim to attract diverse candidates through fair and unbiased selection processes (Jackson & Alvarez, 1992; Shore et al., 2009). Transparent recruitment is crucial for fostering inclusivity in the workplace (Daya, 2014). Genuine commitment from organisational leaders in overseeing recruitment, advancement and retention of diverse employees cultivates an inclusive culture (Gallegos, 2013).

Inclusive Decision-Making

Inclusive decision-making, prioritising diverse perspectives, enhances creativity and innovation, fostering employee engagement and dedication. Nishii and Rich (2013) and Mor Barak and Cherin (1998) stress employee participation’s significance for organisational inclusivity. Shore et al. (2011) and Tang et al. (2015) identify inclusive organisations actively involving diverse inputs in decision-making through open group discussions. Sabharwal (2014) defines organisational inclusion as employees influencing corporate decisions, creating a culture where the workforce actively shapes important choices.

Methodology

ISM technique was implemented to determine and organise the enablers of organisational inclusion. The initial step involved conducting a thorough literature review to compile a comprehensive list of 11 enablers. In total, 15 experts and professors with expertise in workplace diversity and inclusion were engaged to establish the interrelationships among these variables. Purposive sampling was used to select participants based on their expertise and skills. ISM technique requires a brainstorming session with selected experts from the respective field (Goel et al., 2022). The data have been collected from a self-structured questionnaire comprising enablers contributing to organisation inclusivity. Experts were asked to complete a pairwise comparison of the 11 enablers based on the type of relationships among them. Subsequently, the ISM was utilised to delve into the intricate connections between these enablers, leading to insightful conclusions about their interdependencies and their role as a cohesive system in promoting organisational inclusion. Moving forward, the next stage focused on conducting a MICMAC analysis. This analysis allowed for a detailed exploration of the complex relationships among the enablers, which were then categorised into four distinct groups known as ‘autonomous, dependent, linkages and independent variables’. These categorisations provided a deeper understanding of how the enablers interacted and influenced each other within the organisational context, shedding light on their relative importance and impact on achieving inclusivity.

Interpretive Structural Analysis

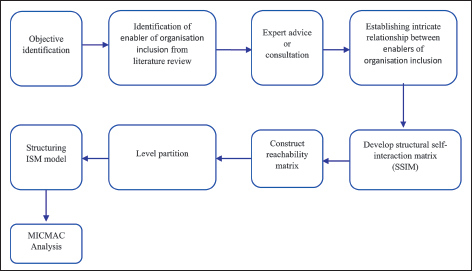

Organisational inclusion is impacted by an array of diverse factors, and understanding the relationships between these factors can be immensely valuable for top management to prioritise their focus areas. ISM framework is employed in complex situations where individuals use their expertise to form subjective assessments regarding the connections among the elements (Malone, 1975). For complex problems like achieving organisational inclusion, multiple enablers may play a major role. However, analysing the explicit and indirect correlations between these enablers offers a more accurate understanding than considering them in isolation. ISM facilitates collective insights into these relationships. ISM is both interpretive and structural. It is interpretive, as the collective judgement of the group shapes the linkages between variables. It holds a structural aspect by inferring a holistic system framework from these associations, depicted in the form of an ISM model. The process of ISM involves a series of steps as shown in Figure 1.

Model Development

Structured Self-Interaction Matrix (SSIM)

After establishing the contextual relationships among various enablers, this stage involves creating a matrix that represents the relationships among various enablers. This matrix is called the structured self-interaction matrix (SSIM) and is shown in Table 1. The purpose of this matrix is to depict how different enablers are related to one another. It uses four symbols to explain the direction of a relationship between enablers:

Figure 1. Flow Chart of the ISM Process.

‘V: indicates that Enabler p will help achieve Enabler’.

‘A: indicates that Enabler q will help achieve Enabler p’.

‘X: indicates that both Enabler p and q will help achieve one another’.

‘O: indicates that Enablers p and q are unrelated’.

For simplicity and ease of presentation, all 11 identified enablers are represented using codes e.g., T1, T2, T3…, as shown in Table 1.

Reachability Matrix

The SSIM is converted into a binary matrix, known as the reachability matrix, through the substitution of V, A, X and O with 1s and 0s based on specific rules. ‘When the SSIM (p, q) entry is V, the reachability matrix entry is 1 and the (q, p) entry is 0. Conversely, if the SSIM’s (p, q) entry is A, the reachability matrix becomes 0 and the (q, p) becomes 1. Both (p, q) and (q, p) in the reachability matrix become 1 when the SSIM entry is X. Finally, if the SSIM (p, q) entry is O, the reachability matrix (p, q) and (q, p) entries become 0’.

Upon applying these rules and considering transitivity, ‘the final reachability matrix’ is obtained (Table 2). The driving power and dependence of each enabler are also indicated in Table 2. The driving power of a variable signifies the extent to which it can contribute to achieving or influencing other variables within the system. It represents the number of variables that the given variable can assist in attaining. Conversely, the dependence power of a variable denotes the degree to which it relies on or is influenced by other variables within the system. It reflects the number of variables that can contribute to attaining the given variable. These driving power and dependence values are crucial for the subsequent MICMAC analysis.

Level Partitions

At this stage, the reachability matrix is used to assess the reachability and antecedent sets for each enabler in the ISM model. The reachability set includes the enabler itself along with other enablers that it is expected to influence. Conversely, the antecedent set comprises the enabler itself and other enablers that are expected to contribute to its attainment. Enablers that appear in both the reachability and antecedent sets are categorised under the intersection set. The ISM hierarchy’s levels are determined based on the intersection and reachability sets being the same. At the highest tier of the structure, the identified enablers do not contribute to achieving any other enablers that lie above their level. Once the uppermost-level enablers are recognised, they are separated from the remaining enablers. This iterative process continues until all enablers find their respective positions in the ISM hierarchy. Each cycle of this process is called an ‘iteration’, and in this case, six iterations have led to the identification of the ISM hierarchy. The final output of iterations 1 to 6 is represented in Table 3, respectively.

Constructing the ISM Framework

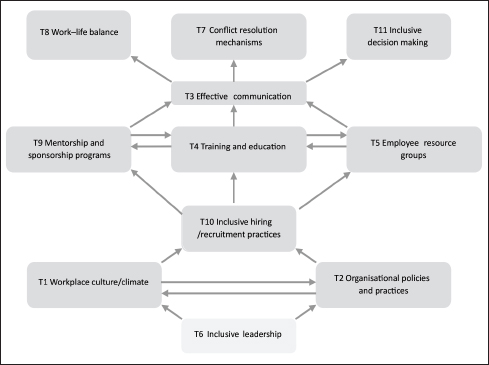

The structural model is constructed based on ‘the final reachability matrix’ and partition table, capturing the relationships among variables using arrows. Each arrow points from a variable that contributes to another variable, indicating the hierarchical level of influence between them. The ISM model is developed by arranging the variables identified during the initial iteration positioned at the uppermost section of the diagram, with subsequent variables positioned downward based on their level of iteration in the partition process. This results in the ISM model as shown in Figure 2. The ISM model reveals that inclusive leadership, organisation policies and practices, and workplace culture play pivotal roles as the driving factors in fostering a more inclusive organisational environment, as they are situated at the lowermost level of the hierarchical arrangement.

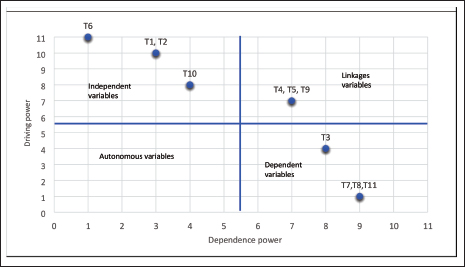

MICMAC Analysis

MICMAC analysis is a principal approach rooted in the properties of matrix multiplication (Nandal et al., 2019), and serves as a valuable tool to investigate the dependence and driving power of variables in the ISM model, aiding in the classification of crucial variables influencing organisational inclusion. The resulting MICMAC graph (Figure 3) displays the variables’ positions based on their dependence power (x-axis) and driving power (y-axis) and categorised them into four distinct clusters. The first cluster, known as autonomous variables, comprises enablers with weak driving power and weak dependence, implying that no variable is entirely detached from the overall system. Thus, the top management needs to address all the recognised enablers of organisational inclusion. The second cluster comprises variables that are dependent on other factors, including enablers with high dependence power but low driving power. Enablers T7, T8, T11 and T3 fall into this category. The third cluster includes variables that serve as links between other enablers, characterised by strong driving power and strong dependence power. Enablers T4, T5 and T9 fall into this group, indicating their importance in driving change and their interconnectedness with other enablers. Lastly, the fourth cluster consists of variables that operate independently and influence other factors, denoting enablers with strong driving power but weak dependence power. Enablers T6, T1, T2 and T10 fall into this group, signifying their key role in promoting organisational inclusivity.

Figure 2. ISM: A Framework for the Factors Facilitating Organisational Inclusion.

Figure 3. MICMAC Analysis.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study utilises the ISM methodology, providing valuable perspectives and a well-organised structure outlining the fundamental drivers of organisational inclusivity. Among the identified enablers, leadership emerged as the most crucial factor influencing organisational inclusivity. Authentic leaders play a significant role in social transformation in terms of conveying the importance of workplace inclusion to employees (Boekhorst, 2015). When leaders treat their team members as valuable contributors, it fosters a sense of acceptance and value, leading to increased feelings of inclusion among employees (Brimhall et al., 2014; Murphy & Ensher, 1999; Schyns et al., 2005). Supervisors can shape employees’ perspectives on inclusion through their interactions, ensuring that employees are aware of diversity and inclusion concerns and how they align with organisational objectives (Daya, 2014). Inclusive leadership involves various approaches including training, incentives, hiring, recruitment and advancement of employees, all of which help shape and embed an inclusive organisational culture (Jaskyte, 2004). Hence, prioritising inclusive leadership is essential for enhancing overall organisational inclusivity.

The study further employs MICMAC analysis to assess the influential and interdependent strength of distinct variables within the established framework. It classified the facilitators into the following four groups: ‘autonomous, dependent, linkage and driving’. Interestingly, all enablers were found to be crucial in making the organisation inclusive, as no variables fell into the autonomous quadrant. Driving factors such as inclusive leadership (T6), workplace culture (T1), organisational policies (T2) and inclusive hiring practices (T10) play a crucial part in driving other inclusion enablers. Inclusive leadership has a positive influence on creating an inclusive workplace culture (Dai & Fang, 2023; Kuknor et al., 2023). It actively fosters diversity and inclusion, establishing a culture marked by respect, fairness and equal opportunities for all employees (Kuknor et al., 2023). Notably, the mere presence of diverse teams does not automatically create an inclusive environment but it necessitates inclusive leadership in cultivating an inclusive climate where diverse team members are genuinely valued for their unique contributions to work practices (Ashikali et al., 2021). Furthermore, inclusive leadership significantly contributes to organisational learning through psychological safety and climate (Nejati & Shafaei, 2023). Leaders demonstrating inclusive behaviours can influence organisational policies and practices that support an inclusive environment (Mor Barak et al., 2022). This evidence establishes inclusive leadership drives both inclusive workplace culture and organisational policies.

Linkage factors include mentorship and sponsorship programs (T9), training and education (T4) and ERGs (T5). On the contrary, effective communication (T3), conflict resolution mechanisms (T7), work–life balance (T8) and inclusive decision-making (T11) were identified as dependent variables, as they are influenced by other factors in the framework. Inclusive leadership plays a crucial role in promoting effective communication and contributing to the development of conflict resolution mechanisms by fostering interpersonal relationships and resolving conflicts on time (Cheryl & Joseph, 2022). Additionally, Ahmad and Chowdhury (2022) highlighted the significant impact of effective communication on interpersonal relationships, conflict resolution and decision-making. Therefore, this research substantiates the interconnectedness of these critical factors with inclusive leadership, affirming its indispensable role in fostering an inclusive environment. Overall, the model resulting from this study emphasises the key enablers that strengthen organisational inclusivity, leading to benefits like innovation, creativity, job satisfaction and high performance (Brimhall & Mor Barak, 2018). Focusing on these enablers will create a more inclusive and thriving workplace where employees experience a sense of worth and empowerment, enabling them to offer their utmost for the company’s growth.

Managerial Implications

This research paper offers valuable contributions for organisations striving to cultivate a more inclusive workplace. Practical applications include as following: (a) Set clear, measurable objectives for increasing diversity within the organisation, considering aspects like gender diversity and ethnicity diversity; (b) Broaden the lens on DEI by implementing strategies that create a rich culture across the entire organisation; (c) Develop inclusive leadership training programs to enhance leaders’ understanding of diversity inclusion and promote authenticity and empathy; (d) Create an environment where leaders actively seek diverse perspectives, encourage open communication and ensure all team members feel heard and valued; (e) Review and update organisational policies to eliminate biases and promote diversity and inclusion in areas such as recruitment, promotion and work flexibility; (f) Ensure diverse representation in hiring panels, implement blind recruitment techniques and create pipeline development programs to attract and retain diverse talent.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

This section explains the limitations and future directions of the study. First, the ISM framework, relying on inputs from specific experts which may introduce biases. Second, the model lacks statistical validation. Another limitation is the number of variables. Despite conducting a comprehensive literature review, some factors might be overlooked. Opportunities for future research involve evaluating the model’s reliability through structural equation modelling. Additionally, research shows that systematic change at the individual, interpersonal and organisational levels create inclusion (Daya, 2014). This study did not explore interpersonal- and personal-level enablers of inclusivity within organisations. Future research could address this aspect to enhance the model’s comprehensiveness and effectiveness.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to the anonymous referees of the journal for their extremely insightful suggestions to improve the quality of the paper.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

Sunita Tanwar  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4471-6487

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4471-6487

Nisha Yadav  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7277-3999

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7277-3999

Ahmad, A., & Chowdhury, D. (2022). A review of effective communication and its impact on interpersonal relationships, conflict resolution, and decision-making. Review of Applied Socio-Economic Research, 24(2), 18–23.

Ashikali, T., Groeneveld, S., & Kuipers, B. (2021). The role of inclusive leadership in supporting an inclusive climate in diverse public sector teams. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 41(3), 497–519. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X19899722

Aysola, J., Barg, F. K., Martinez, A. B., Kearney, M., Agesa, K., Carmona, C., & Higginbotham, E. (2018). Perceptions of factors associated with inclusive work and learning environments in health care organizations: A qualitative narrative analysis. JAMA Network Open, 1(4), e181003–e181003.

Bhanu, R. (2022). Achieving an inclusive work culture: Factors contributing to establish inclusivity in growing SMEs of India. ECS Transactions, 107(1), 20057–20063. https://doi.org/10.1149/10701.20057ecst

Boekhorst, J. A. (2015). The role of authentic leadership in fostering workplace inclusion: A social information processing perspective. Human Resource Management, 54(2), 241–264.

Booysen, L. (2013). The development of inclusive leadership practices and processes. In B. R. Deane & B. M. Ferdman (Eds.), Diversity at work: The practice of inclusion (pp. 296–329). Wiley.

Bohonos, J. W., & Sisco, S. (2021). Advocating for social justice, equity, and inclusion in the workplace: An agenda for anti-racist learning organizations. New Directions in Adult and Continuing Education, 2021(170), 89–98.

Brickson, S. (2000). The impact of identity orientation on individual and organizational outcomes in demographically diverse settings. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 82–101.

Brimhall, K. C., Lizano, E. L., & Barak, M. E. M. (2014). The mediating role of inclusion: A longitudinal study of the effects of leader-member exchange and diversity climate on job satisfaction and intention to leave among child welfare workers. Children and Youth Services Review, 40, 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.03.003

Brimhall, K. C., & Mor Barak, M. E. (2018). The critical role of workplace inclusion in fostering innovation, job satisfaction, and quality of care in a diverse human service organization. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 42(5), 474–492.

Carmeli, A., Reiter-Palmon, R., & Ziv, E. (2010). Inclusive leadership and employee involvement in creative tasks in the workplace: The mediating role of psychological safety. Creativity Research Journal, 22(3), 250–260.

Cheryl, E., & Joseph, J. G. (2022). Analyzing inclusive leadership with effective communication: A thematic study. International Journal of Science Engineering and Management, 9(7), 18–20.

Cottrill, K., Denise Lopez, P., & C. Hoffman, C. (2014). How authentic leadership and inclusion benefit organizations. Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion: An International Journal, 33(3), 275–292.

Cox, T. (2001). Creating the multicultural organization: A strategy for capturing the power of diversity. Jossey-Bass.

Dai, X., & Fang, Y. (2023). Does inclusive leadership affect the organizational socialization of newcomers from diverse backgrounds? The mediating role of psychological capital. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1138101. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1138101

Davidson, M. N. (1999). The value of being included: An examination of diversity change initiatives in organizations. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 12(1), 164–180.

Davidson, M. N., & Ferdman, B. M. (2002). Inclusion: What can I and my organization do about it? The Industrial-Organizational Psychologist, 39(4), 80–85.

Daya, P. (2014). Diversity and inclusion in an emerging market context. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, 33(3), 293–308.

Deloitte. (2012). Waiter, is that inclusion in my soup? A new recipe to improve business performance. Deloitte Australia.

Dennissen, M., Benschop, Y., & van den Brink, M. (2020). Rethinking diversity management: An intersectional analysis of diversity networks. Organization Studies, 41(2), 219–240.

Douglas, P. H. (2008). Affinity groups: Catalyst for inclusive organizations. Employment Relations Today, 34(4), 11–18.

Ferdman, B. M., Avigdor, A., Braun, D., Konkin, J., & Kuzmycz, D. (2010). Collective experience of inclusion, diversity, and performance in work groups. Mackenzie, 11(3), 6–26.

Findler, L., Wind, L. H., & Barak, M. E. M. (2007). The challenge of workforce management in a global society: Modeling the relationship between diversity, inclusion, organizational culture, and employee well-being, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment. Administration in Social Work, 31(3), 63–94.

Friedman, R. A., & Holtom, B. (2002). The effects of network groups on minority employee turnover intentions. Human Resource Management, 41(4), 405–421.

Gallegos, P. V. (2013). The work of inclusive leadership. In B. R. Deane & B. M. Ferdman (Eds.), Diversity at work: The practice of inclusion (pp. 177–202). Wiley.

Gehrels, S., & Suleri, J. (2016). Diversity and inclusion as indicators of sustainable human resources management in the international hospitality industry. Research in Hospitality Management, 6(1), 61–67.

Goel, P., Kumar, R., Banga, H. K., Kaur, S., Kumar, R., Pimenov, D. Y., & Giasin, K. (2022). Deployment of interpretive structural modeling in barriers to industry 4.0: A case of small and medium enterprises. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(4), 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15040171

Hagner, D. (2000). Coffee breaks and birthday cakes: Evaluating workplace cultures to develop natural supports for employees with disabilities. Training Resource Network.

Henderson, E. (2013). The Chief Diversity Officer’s view of the diversity and inclusion journey at Weyerhaeuser. In B. R. Deane & B. M. Ferdman (Eds.), Diversity at work: The practice of inclusion (pp. 431–450). Wiley.

Higginbotham, E. J. (2015). Inclusion as a core competence of professionalism in the twenty-first century. The Pharos of Alpha Omega Alpha-Honor Medical Society. Alpha Omega Alpha, 78(4), 6–9.

Hill, S. E. K., & Gant, G. (2000). Mentoring by minorities for minorities: The organizational communications support program. Review of Business, 21(1/2), 53–57.

Hirak, R., Peng, A. C., Carmeli, A., & Schaubroeck, J. M. (2012). Linking leader inclusiveness to work unit performance: The importance of psychological safety and learning from failures. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(1), 107–117.

Hu, C., Thomas, K. M., & Lance, C. E. (2008). Intentions to initiate mentoring relationships: Understanding the impact of race, proactivity, feelings of deprivation, and relationship roles. The Journal of Social Psychology, 148(6), 727–744.

Jackson, S. E., & Alvarez, E. B. (1992). Working through diversity as a strategic imperative. In Diversity in the workplace: Human resource initiatives (pp. 13–29). Guilford Press.

Jadaun, R. (2023). An empirical study of factors affecting inclusive workplaces: A framework for diversity management. Psychology and Education, 55(1). https://doi.org/10.48047/pne.2018.55.1.06

Jain, D. (2020). Inclusion—The ecosystem for Diversity to thrive! LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/inclusionecosystem-diversity-thrive-divya-jain/

Janssens, M., & Zanoni, P. (2008). What makes an organization inclusive? Work contexts and diversity management practices favoring ethnic minorities’ inclusion.

Jaskyte, K. (2004). Transformational leadership, organizational culture, and innovativeness in nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 15(2), 153–168.

Johnsen, T. L., Fyhn, T., Jordbru, A., Torp, S., Tveito, T. H., & Øyeflaten, I. (2022). Workplace inclusion of people with health issues, immigrants, and unemployed youths—A qualitative study of Norwegian leaders’ experiences. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 687384. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.687384

Johnson-Bailey, J., & Cervero, R. M. (2004). Mentoring in black and white: The intricacies of cross-cultural mentoring. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 12(1), 7–21.

Khan, R. (2023). Enablers to build Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in the organization. The People Management. https://thepeoplemanagement.com/enablers-to-build-diversity-equity-and-inclusion-in-the-organization-rubi-khan-avp-people-initiatives-talent-management-od-diversity-inclusion-max-life-insurance-company-limited/

Kuknor, S., Bhattacharya, S., Sharma, B. K., & Bhattacharya, S. (2023). Organizational inclusion and OCB: The moderating role of inclusive leadership. FIIB Business Review. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/23197145231183859

Malone, D. W. (1975). An introduction to the application of interpretative structural modeling. Proceedings of the IEEE, 62(3), 397–404.

Mor Barak, M. E., & Cherin, D. A. (1998). A tool to expand organizational understanding of workforce diversity: Exploring a measure of inclusion-exclusion. Administration in Social Work, 22(1), 47–64.

Mor Barak, M. E., Cherin, D. A., & Berkman, S. (1998). Organizational and personal dimensions in diversity climate: Ethnic and gender differences in employee perceptions. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 34(1), 82-104.

Mor Barak, M. E., Luria, G., & Brimhall, K. C. (2022). What leaders say versus what they do: Inclusive leadership, policy-practice decoupling, and the anomaly of climate for inclusion. Group & Organization Management, 47(4), 840–871.

Murphy, S. E., & Ensher, E. A. (1999). The effects of leader and subordinate characteristics in the development of leader–member exchange quality. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29(7), 1371–1394.

Nandal, V., Kumar, R., & Singh, S. K. (2019). Barriers identification and analysis of solar power implementation in Indian thermal power plants: An Interpretative Structural Modeling approach. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 114, 109330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2019.109330

Naseer, S., Bouckenooghe, D., Syed, F., & Haider, A. (2023). Power of inclusive leadership: Exploring the mediating role of identity-related processes and conditional effects of synergy diversity climate in nurturing positive employee behaviors. Journal of Management & Organization, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2023.37

Nautiyal, M. (2018). The intersection of diversity, equity, and inclusion in management practices: A descriptive study. Psychology and Education, 55(1). https://doi.org/10.48047/pne.2018.55.1.74

Nejati, M., & Shafaei, A. (2023). The role of inclusive leadership in fostering organisational learning behaviour. Management Research Review, 46(12), 1661–1678.

Nembhard, I. M., & Edmonson, A. C. (2006). Making it safe: The effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(7), 941–966.

Nguyen, T. V. T., Nguyen, H. T., Nong, T. X., & Nguyen, T. T. T. (2022). Inclusive leadership and creative teaching: The mediating role of knowledge sharing and innovative climate. Creativity Research Journal, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2022.2134543

Nishii, L. H., & Rich, R. E. (2013). Creating inclusive climates in diverse organizations. In B. R. Deane & B. M. Ferdman (Eds.), Diversity at work: The practice of inclusion (pp. 330–363). Wiley.

Offerman, L. R., & Basford, T. E. (2014). Best practices and the changing role of human resources. In B. R. Deane & B. M. Ferdman (Eds.), Diversity at work: The practice of inclusion (pp. 229–259). Wiley.

Pelled, L. H., Ledford, G. E., & Mohrman, S. A. (1999). Demographic dissimilarity and workplace inclusion. Journal of Management Studies, 36(7), 1013–1031.

Roberson, Q. M. (2006). Disentangling the meanings of diversity and inclusion in organizations. Group and Organization Management, 31(2), 212–236.

Sabharwal, M. (2014). Is diversity management sufficient? Organizational inclusion to further performance. Public Personnel Management, 43(2), 197–217.

Schein, E. H. (1992). Organizational culture and leadership. Jossey-Bass.

Schein, E. H. (2004). Organizational culture and leadership. Jossey-Bass.

Schyns, B., Paul, T., Mohr, G., & Blank, H. (2005). Comparing antecedents and consequences of leader–member exchange in a German working context to findings in the US. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 14(1), 1–22.

Shore, L. M., Chung-Herrera, B. G., Dean, M. A., Ehrhart, K. H., Jung, D. I., Randel, A. E., & Singh, G. (2009). Diversity in organizations: Where are we now and where are we going? Human Resource Management Review, 19(2), 117–133.

Shore, L. M., Randel, A. E., Chung, B. G., Dean, M. A., Ehrhart, K. H., & Singh, G. (2011). Inclusion and diversity in work groups: A review and model for future research. Journal of Management, 37(4), 1262–1289

Tang, N., Jiang, Y., Chen, C., Zhou, Z., Chen, C. C., & Yu, Z. (2015). Inclusion and inclusion management in the Chinese context: An exploratory study. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(6), 856–874.

Theodorakopoulos, N., & Budhwar, P. (2015). Guest editors’ introduction: Diversity and inclusion in different work settings: Emerging patterns, challenges, and research agenda. Human Resource Management, 54(2), 177–197.

Thomas, D. A. (1990). The impact of race on managers’ experiences of developmental relationships (mentoring and sponsorship): An intra-organizational study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 11(6), 479–492

Wasserman, I. C., Gallegos, P. V., & Ferdman, B. M. (2008). Dancing with resistance: Leadership challenges in fostering a culture of inclusion. In K. M. Thomas (Ed.), Diversity resistance in organizations (pp. 175–200). Taylor & Francis Group.

Welbourne, T. M., Rolf, S., & Schlachter, S. (2017). The case for employee resource groups. Personnel Review, 46(8), 1816–1834.